He wasn’t trying to spear me, I didn’t think, just give me a bit of scare. I dodged out of the way as I saw another one coming but the tip caught me in the side in the rib cage. That hurt too. I was unlucky; not quick enough. So when I saw a third one coming my way, I’d had enough. I grabbed his rifle by the barrel and with tremendous force pulled it out of his hand and threw it on the ground. It was a bloody stupid thing to do as there was bound to be a round of ammunition in the gun. I knew it because their rifles were meant to be loaded at all times. It might have triggered off and killed either one of us or one of my friends. What a stupid thing to do! Me and my temper. If I had killed a German guard that would have been certain death.

My two pals ran to me and got between me and Jan. Jimmy was shouting at me, pretending to tell me off, and Laurie was holding me off with one hand and waving the other at Jan as though to say, ‘It’s OK, OK, I’ve got him.’ Jan looked as though he had had enough. He was thinking, ‘I’ve given him a fright, shown him who’s in charge, and his mates have got him now and are telling him off.’ I took deep breaths and then let go and felt Jimmy and Laurie holding me, taking control.

Another guard arrived to take over from Jan. Jimmy and Laurie marched me away and told me what a bloody idiot I was. They were cross and said, ‘You could have got yourself killed.’ I looked over my shoulder and saw that Jan had retrieved his rifle and was checking the bayonet. I saw from his face and gestures that he was telling guard No 2 about what had happened. Telling him all about me and what I had done to the soup and to him. He disappeared and we went back to the hay barn to finish the job.

It was painful trying to work, especially bending down and stretching up. My chest and ribs hurt and my shoulder felt as though it was coming out of its socket. I opened my tunic a little and rubbed the area through my vest. It was sore. There was bruising; it would be purple by morning. I carried on working, well, going through the motions. Afternoon turned into evening. There was another change of guard and we finished about seven and marched back to our camp.

Nobody said anything on the way home but we all returned in a good mood, looking forward to something to eat, especially me. Anything to take the edge off the awful hunger. No breakfast and my lunch left on the ground in the farmyard so I hoped that there was a bit of Wurst that night.

Word had got round about the incident, presumably from our cooks and as I entered the camp yard, some of the chaps who had returned earlier called out, ‘All right, Tyro, what you been up to, then?’ Some of the chaps used that nickname. Apparently Tyro was an Indian word for ‘Wait’ and I suppose I got it, not just because of my surname but because I had been known to get a bit impatient over things. One of the cooks joined in: ‘Fancy some soup, then, or shall I cut out the middle man and chuck it straight on the floor?’ They knew about the trouble with the guard and wanted to know more.

‘Go on, Tyro, what you do?’ But we were interrupted by the Unteroffizier calling us all to order. Everybody was told to go inside except me. ‘ Hier bleiben,’ – stay here, he said. What was this? I was thinking. This looked like trouble. I was worried then because Jan had obviously reported me or word had got back to the Unteroffizier from the other guard. I didn’t know what was going to happen next. They were not going to forget it. I was going to be charged, wasn’t I? Charged and punished.

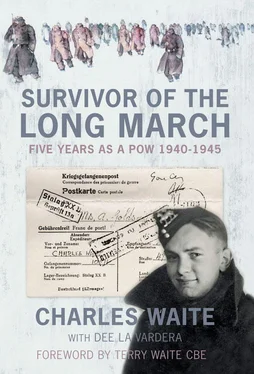

The officer said, ‘Name und Nummer ,’ – give me your name and number, which I did. ‘Private Charles Waite Number 10511,’ and added ‘ Mein Herr .’ He handed me a postcard on which was typed in English ‘POW Charles Waite No 10511 is to be taken to the Kommandant at Headquarters under arrest on a charge of Incitement to Mutiny.’ Mutiny! I couldn’t believe it. That frightened the life out of me. My heart was pounding and I could hardly breathe. I felt as though I was going to faint because I knew, I knew what the penalty was for such a serious charge.

Mutiny. In Germany in the First World War that meant a man could be shot so there was no reason for this lot to behave any differently. I was scared to death. I thought of my mother and of Lily, how upset they would be. All the family.

The officer said, ‘ Komm hier früh,’ – be here early, ‘ um sechs Uhr morgens,’ – at six o’clock in the morning. He walked off sharply and I was left standing there alone. When I went in and told the others, my pals tried to reassure me, ‘Don’t worry, Chas. You’ll be back.’ And ‘You haven’t hurt anyone. It’s just to put the wind up you. Don’t worry about it.’ But I was worried, very worried. Incitement to Mutiny. Headquarters. Kommandant . You couldn’t forget that.

I couldn’t get to sleep for thinking about it. I lay awake in my bunk listening to the strange noises in the night and worrying. Oh, God, spare me, I prayed. I was up well before the time and everybody wished me good luck. ‘See you later, Chas,’ and ‘Chin up, Tyro.’ I went and waited by the main entrance for the guard and it was Jan who was going to escort me to HQ.

We set off walking towards Freystadt and arrived at the station about half an hour later, where a train was waiting. It was just an engine and two carriages and we headed for the first one. Nobody else was allowed on and I saw people – civilians, being directed to the rear carriage. A guard shouted, ‘ Hier nicht ,’ – not here, and pointed saying, ‘ Im hinteren Wagen ’ – the rear carriage. When I got inside I went to sit down but Jan indicated with his rifle for me to get up. I stood at the back while Jan made himself comfortable on a seat in the middle of the empty carriage.

After about twenty minutes, the train stopped and we got off and went on another train with a single carriage. When we arrived at our destination, about an hour later, we had to climb down and cross the railway tracks to get to the main road. It was empty countryside for miles around. No signs or landmarks. We didn’t talk or communicate in any way as we walked side by side, a short distance apart. All the time I was frightened, thinking about the charge, where we were going and what was going to happen.

Suddenly we came to a sharp bend and as we rounded it the barracks appeared ahead. The battalion headquarters were massive, thousands of German troops were stationed there. There was a field to the left with half a dozen small planes, which looked like observation aircraft. Jan led the way, marching smartly now, as we approached the main gates where two guards outside checked our papers, and opened the gates. As soon as we were through and standing in a small square, they locked the gates and we walked towards another set of gates. Two more guards repeated the palaver and we went through the gates into a larger square with buildings all around. I had no idea where I was. I didn’t recognise anything. I wondered if I would ever get out of there, back to my pals at the camp.

Jan asked a guard something, probably where the guardhouse was, and the guard pointed across the way. The place was noisy and busy with people coming and going. As I stood there, I felt very small and very afraid. I was nothing. Nobody. Off we went again with Jan pushing me forward to the entrance to a building and up some wooden steps. We went along a corridor and up more steps into a huge hall with high ceilings and a beautiful polished floor. There wasn’t any furniture in the room and I felt even more afraid in these surroundings. Still not saying a word to me, Jan pushed me against a wall, and I stood to attention automatically.

Читать дальше

![Джеффри Арчер - The Short, the Long and the Tall [С иллюстрациями]](/books/388600/dzheffri-archer-the-short-the-long-and-the-tall-s-thumb.webp)