He stepped away from the window and came to me. He led me to the door, pointed at the bay, and said, “Three ships sank here, and thousands of people drowned. I wasn’t here when it happened, but for years bones drifted up to the shore. Many a time I found some myself on the beach.” I was here on a pilgrimage, to recover all the secrets he had willingly shed. But then an elderly woman came in, and the man greeted her. I knew that our conversation was over and that this was all I would learn from him. I left with a heavy heart full of painful memories. I had revisited a nightmare.

In July 1985 I joined a group of Jewish men and women from the United States on a fact-finding mission to Eastern Europe. We went to Poland. Each site brought back more bitter memories. This is where it all began. At Auschwitz, where civilization once ceased, time and weather had rotted the structures and watchtowers of the camp. Children now played there, unconscious that they were walking on the same spot where thousands of Jewish kids took their last steps. Lawns and houses had replaced the once bare landscape. In Birkenau lay shambles of the noxious crematorium. The sign over the gate, “Arbeit Macht Frei,” obscene and offensive, was still there. There were many tourists reading on a marker that four million people had been killed there. It didn’t tell the real story.

The Block Smierci, the death block where I saw the showcase of inhumanity, was most poignant: stacks of clothes, shoes of all sizes—large, small, and even tiny baby shoes—suitcases with names, mounds of human hair, eyeglasses, canes, teeth, and other personal objects. I had not seen this before. It filled me with so much pain that I couldn’t fathom it.

Outside the block, I stood transfixed and looked up to the sky. Where are the souls of the millions of people who rose up in ashes? Now, I thought, the guilty prosper, raise families, and are good fathers and grandfathers.

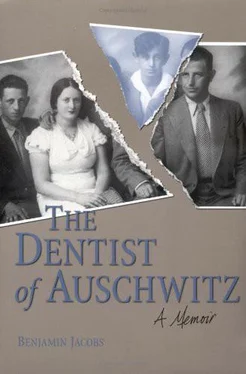

I went to the museum’s archival offices. When I gave my name, Tadeusz Iwashko, the archivist, said to me. “We know who you are. You were the dentist in Auschwitz III, Fürstengrube.” Then he reached out and pulled a book from a shelf. Its title was Hefte von Auschwitz . “Look inside,” he said. “You’ll find your name and number there, and your father’s and brother’s.” I read with glassy eyes my name, Bronek Jakubowicz, number 141129, and the numbers of my father and brother. Another note told of my posting as a dentist in Fürstengrube.

To fulfill a secret desire within me, I went to my former home, the little village of Dobra, where I was born and lived for nearly twenty-two years. When I was arrested in 1941, I left there with bitter memories. After the war, not a single Jewish person returned to Dobra, where Jews had lived for five hundred years. The gravestones from the Jewish cemetery paved the village sidewalks. I sat for a long time in silence, gripped with pain. Then I began to cry.

When I raised my head, an old woman with a weather-beaten face stared at me. “I live just a couple of houses from yours. I knew your mother very well before she and your sister, Pola, were deported. Esther said to me, ‘Milka! If we are to see one another again, it will have to be in the other world.’” An irony suddenly struck me: Dobra means good in Polish.

I drove the road to Chelmno that my sister and mother were once driven along. Suddenly Dr. Schatz’s confession unfolded before my eyes. There Mama and Pola suffocated, and there they died.

Despite the sunny day Chelmno seemed bleak and dreary. It was a painfully morbid and desolate place. Four hundred thousand Jews were killed there, and in retaliation for the mid-1942 assassination of SS Obergruppenführer Reinhard Heydrich, two thousand Christian children from Lidice, Czechoslovakia, were also murdered. One monument depicted the twisted faces of victims. With gut-wrenching indignation I read what was below, words written by the few Jews kept in a room to process the bodies arriving daily for the crematorium: “We are writing with our blood to let the world know that these are our last days. Here we are being killed by bullets and gassed—our bodies burned—our ashes are being spread in this forest!” Above this was a single giant word, Pamitamy (Remember). I will remember the images of that day forever.

Chelmno’s crematorium was capable of turning 5,000 bodies each day to ashes, I also read, more even than those in Auschwitz. The maximum at Auschwitz was 4,600. Here were the souls of my mother and my sister!

Seeing Chelmno was more painful for me than being at Auschwitz. A few German students were standing there at the monument, also visibly moved. I wondered how their fathers and grandfathers would explain this to them.

I left the country where my family and my ancestors had lived for years, relieved that I did not live there anymore. I no longer looked upon Poland as my home, and I had forever cut my ties with my former homeland. I returned to Boston with a renewed spirit, with a sense of homecoming.

I still can’t believe that all of this happened to me—in one lifetime. I have not spent much time examining the unanswered questions: Who was to blame for this? Could any of it have been prevented? If it could have been, why wasn’t it? These and many other remaining questions are the assignment for the future. Perhaps more light is necessary to explain this stormy phase in our people’s history.

APPENDIX A

The Sinking of the Cap Arcona

In what is apparently the only English-language article on the Cap Arcona sinking, J.L. Isherwood writes in a British periodical:

The Cap Arcona , launched on May 14, 1927, was probably the most luxurious ship on the Hamburg to South America route until the second World War….

In April 1945, with the Russian quick advance, in three of her trips, she evacuated 26,000 Germans on the Baltic from east to west. Thereafter, in April 1945, she took on 6,000 concentration camp prisoners.

It was while in this capacity, lying in Travemünde bay with a number of other ships, that on May 3 British bombers attacked the port. A number of ships were sunk, the largest being the Deutschland and the Cap Arcona . Including the prisoners, guards and ship’s crew, she had aboard at the time about 6,000 people.

Severely damaged and set on fire by the bombs, the Cap Arcona eventually capsized and the appalling death toll was estimated at 5,000 people.

The wreck of the charred and twisted steel of the Cap Arcona , the tomb of 5,000 bodies, lay for nearly five years. In 1949 it was broken up for scrap metal. [7] J.L. Isherwood, “Steamers of the Past: The Hamburg-South American Liner Cap Arcona ,” Sea Breezes , May 1976.

Isherwood’s account is borne out by British Operations Record Books, labeled “Secret” and obtained for me by the Hamburg-Südamerika Dampfschiffahrts-Gesellschaft and the Hamburg-Amerika line.

Detail of Work Carried Out by 197 Squadron for the Month of May 1945

[Time up, 1515; time down, 1635] DD771. Shipping strikes in Lubeck Bay. All the bombs were dropped on a motor vessel of 15/20.000 tons at 0.0208. The ship was already burning as a result of attacks by 263 Squadron and we scored two direct hits. Now left burning in five places and later seen capsized and burning, CAT. I. [8] Operations Record Book, AIR 27/1109, 5822, p. 1, Public Record Office, London.

APPENDIX B

For the Record

From the Records of the Auschwitz Museum

SS-Unterscharführer Karol Baga: Baga was the Sanitätsdientsgefreiter at Auschwitz I and at Fürstengrube between May 1944 and January 1945. In light of his willingness to cooperate with the Polish investigation authorities, he served only a brief sentence in the Kraków penitentiary.

Читать дальше