We were taken to a major. We still felt apprehensive around authorities, especially the military. That fear continued long after the war. The major was about fifty years old, with a short haircut and a neatly trimmed mustache. He opened a package of cigarettes and offered each of us one. Then he leaned back in his chair and asked in English which one of us spoke his language. I nodded and told him that I spoke a little English. He prepared to take notes. He asked my name and where I was from.

We were concerned about being forced to repatriate to Poland. A rumor that this might happen was circulating at that time. I remembered Max Schmidt’s suggestion. “We’re from France,” I said.

He asked how we got on the Cap Arcona and how it sank. When I told him in my limited English that we saw RAF planes bombing the ship, his chin dropped, and his eyebrows rose in disbelief. Intrigued, he asked more, and then it became apparent that my English was insufficient to fully describe the event. The major called an interpreter. A pretty German girl of about twenty came in and translated his questions into German for me and my answers into English for him. She was visibly moved by the account of our experiences.

The major and lieutenant listened politely. At the end of our interview, the major suggested that we leave the area because of the ongoing fighting. Of course we didn’t have transportation. Having seen many abandoned vehicles on the way here, we hoped he would permit us to take one of the cars now littering the roads. He understood the connection. “I can’t give you permission,” he said, friendly but firm. “There are so many are out there, though. Just take any vehicle you can use. No one will stop you.” As for our personal identification, he said, “Your tattoos will sufficiently identify you.”

We were excited, and ten of us went to look for the right vehicle. We explored all the cars around, but one car couldn’t take us all, so we decided to look for a truck. We searched until we were almost out of town. Then we saw a bus with camouflage war paint. It was a Peugeot, still in good condition. My father had once owned a Peugeot truck. I looked around inside, but the keys were nowhere to be found. It was the perfect vehicle for us, and we wondered what to do. We decided to go into the house and ask the farmer if he had the keys. He claimed that the bus wasn’t his, but we thought that he had the keys nonetheless. We were determined to take that bus. When we insisted and threatened him, he went to the bedroom and returned, trembling, with the keys in his hand. He claimed he forgot his wife had put them there.

I started it up and began backing it out onto the narrow street. I had had only limited experience driving a large vehicle, and I soon got into a situation in which I could go neither forward nor backward. The engine stalled. I tried to get it going, but it kept stalling, and I finally gave up. Disappointed, we left that bus standing and went to look for another one.

We must have looked at fifty vehicles without finding a bus like the one we had just left. It was late in the afternoon. We were dulling our hunger with slices of my brother’s wheel of Swiss cheese. We searched until we came upon two Italian-made Fiats that looked as if they had just come off the assembly line. The keys were in them, and we decided to take them.

My brother started one, and I the other. We were driving west, as the major had suggested, deeper into the occupied territories. We greeted the soldiers on every Allied vehicle we passed with waves. They looked at us with misgivings, wondering who the bony-faced people in striped suits and shabby German naval uniforms were. The landscape was now free of swastikas. In their place lay the reminders of war: burned-out cars, trucks, and tanks. Among the people walking on the road was a tall, slightly hunched man carrying a bundle on a stick. He was swaying from side to side and lurching forward as if he had been on the road a long time. As we passed him. someone said, “It’s Ohlschläger, the SS guard from Fürstengrube.” We stopped, and he continued walking calmly toward us. When he came close we asked him if he knew who we were. He acted evasive and answered no.

“Are you not Ohlschläger, the guard from Fürstengrube?”

This convinced him that it would make no sense for him to deny it. “Yes,” he said, stuttering, “but I had nothing to do with the camp.” We soon became accustomed to hearing this denial. “I just did my duty. I was just a tower guard.” This was another excuse we would hear repeatedly. Now Ohlschläger was no longer the brazen SS trooper. He feared us as we had once feared him.

He embodied all evil to us. Our bitterness and anger were difficult to contain. Some said we should kill him. We all wished him death, but no one wanted to be the executioner. He was repeating his defense. “I was just a plain man doing my duty,” he said over and over. Our positions had suddenly reversed, and he was helpless. We were unsure what we should do with him. We were intoxicated with our new freedom and found it easy to forgive. But he did not walk away scot-free. We gave him a few well-deserved kicks and slaps, and then we left him. His real punishment, we believed, was the defeat of his Führer’s Nazi theory. That should bring him enough disgrace. Later we agonized over why we had not dealt more harshly with him.

As we continued driving, we came to Neu Glassau. By then the sun had set. We had nowhere to go, so we decided to drive by the Schmidts’ barn, take the cutoff, and go to their house. In front of their mansion was a circular driveway lined with trees. A few of our former fellow inmates who were still there were astonished to see us. They still wore striped suits, as did most of our party. They told us that they had survived by hiding in and around the barn. Unfortunately some others were not so lucky; they had been discovered and shot. Josef Hermann was also there. He preferred to be called Hermann Josef now. Schmidt, our former Kommandant, was gone.

The elder Schmidts, whom we had not seen before, came out of the house and greeted us. He was a well-to-do farmer, a dapper suntanned man of about fifty. She was a plump, well-mannered lady. Max was their only child, they said. They had one of their pigs slaughtered for dinner that night and asked us politely to stay. Whereas just days ago we were Unmenschen and, like cattle, had slept in and around their barn, now we were suddenly honored guests having dinner in the house of our Kommandant’s parents. Had our lives taken this big a turn? No German had treated us like this before. Before dinner they served wine and schnapps. For many of us, this was our first drinking experience in years. By the time the pig was cooked and brought to the table, some of us were half drunk, or at least lightheaded. The table was festive, as if set for a joyous celebration, covered with fine china and crystal.

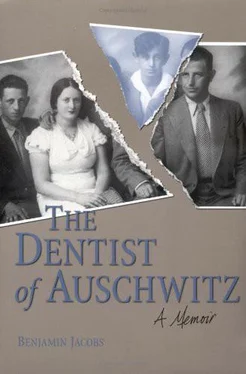

In this gaiety and frolicking, the time was apparently right for a surprise to be sprung on us. In walked Max Schmidt with a bright, friendly smile on his face, his hair cropped. He came up to each of us sitting around the table to shake hands. To me he stretched out his arms as if I were his closest pal. “Dentist, how nice that you survived. Too bad that Bernadotte wouldn’t take you to Sweden.”

Although I regarded his advice about Sweden as the best deed of his that I could remember, I asked him how he knew I was not in Sweden. “You were not around when we were returned,” I said to him. He let it go by, and I did not pursue it any further.

Here we were, pampered guests in Schmidt’s house eating a special meal prepared for us. The former Lagerführer sat at the same table as we did, and we all ate and drank merrily together. “Let’s not talk about the past. Forget what has happened. It was a terrible time for all of us,” Schmidt said. Then he rolled up the left sleeve of his shirt and showed us a number on his arm, just like the ones that all of us had. I couldn’t see whether it was tattooed or painted. That seemed not to upset us. We let everything pass with laughter. The prevailing attitude was one of forgiveness.

Читать дальше