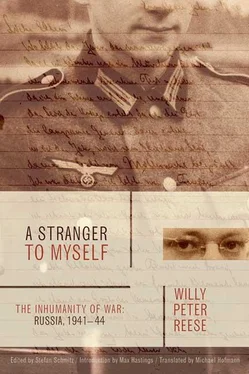

Willy Reese - A Stranger to Myself

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Willy Reese - A Stranger to Myself» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Город: New York, Год выпуска: 2011, ISBN: 2011, Издательство: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, Жанр: Биографии и Мемуары, military_history, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:A Stranger to Myself

- Автор:

- Издательство:Farrar, Straus and Giroux

- Жанр:

- Год:2011

- Город:New York

- ISBN:978-1-42999-875-8

- Рейтинг книги:4 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

A Stranger to Myself: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «A Stranger to Myself»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

is an unforgettable account of men at war.

A Stranger to Myself — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «A Stranger to Myself», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

We hunkered down in the doorways and saw the villages, fields, woods, and pastures of home slip past us, waved to the girls, and sang our songs into the rushing wind.

It wasn’t much before midnight that we finally fell asleep on the boards, shaken about in our carriage, pursued by dreams, and we woke not long after. It seemed to have barely gotten dark at all.

For a long time I looked at the flat meadowland with its half timbered houses and scattered groups of trees. Sometimes the scenery reminded me of the Darss. Towns and empty expanses rolled by. We kept seeing birch trees beside the line, and yarrow, Aaron’s rod, and grass bending in the wind as we passed. The same little wood seemed to come round again, the solitary tree, the field track, the road, the stream. The aspect of the landscape was slow to change.

I was indifferent to the noise and commotion of the soldiers in the wagon with me. I was quiet and calm, oddly equable. When I looked at the ordinary people outside, working in their fields and gardens, I remembered that I was traveling to Russia to fight, to destroy seed and harvest, to be a slave of the war, but then, out of danger and nearness of death, I would feel a lofty freedom and an almost pleasurable sense of life. I was overcome by homesickness. Sorrow at parting and loneliness made me sad, and of course I was frightened of what lay ahead. Certainly there was nothing familiar.

In spite of that, I wasn’t wrestling with my fate. I yearned with a passionate impatience for whatever was awaiting me. I was still young enough to desire anything new, to relish the excitement of the journey, and to intoxicate myself with dreams and fantasies. I didn’t think much of death and danger; distance pulled me toward it. The array of what I saw outside and the atmosphere of our departure filled me with an unspecified joy. Melancholy recollections mingled with stoicism toward the present; worry and grief with a boisterous pleasure in being alive. I felt as unhappy and consumed by bliss as if I were in love.

And so I entered the magical space of adventures. It was the beginning of a long journey.

The next night also passed without sleep. It was very early in the morning when we crossed the border into conquered and once more partitioned Poland. [8] Reese is stationed in this small town (which today is in southern Poland) from August 24 to September 24, 1941. Following the German attack on Poland, Soviet troops occupied the east of that country. Jaroslaw was close to the new demarcation line.

Flat country and distant hills characterized the sparse scenery. Stubble fields with shocks of corn, pastures with the drying hay from the last mowing of the year, small villages, and low, functional houses, wide streets, and neglected gardens filled in the space between the cities: Łódź, Kraków, Katowice… Barefoot women went about their work, with kerchiefs tied over their dark hair, and skirts bleached to some indistinguishable color by the sun. Ragged, neglected children begged for bread. They ran along beside the train, holding out their bony hands, or stood there accusingly, an image of hunger and abject poverty. Their pleas and their thanks sounded equally foreign to my ear. We had little enough to eat for ourselves. Their poverty was strange to us too; it didn’t resemble our native poverty in Germany, and we didn’t really understand it. We were not yet acquainted with hunger and inflation; it was our first meeting with a people who spoke a different language, with a different attitude, another purpose.

I saw no enemies, only conquered people. Only strangers. No path led to their souls and spirits, and from the moving train I had little sense of their day-to-day existences, their happiness and their grief. I did nothing and didn’t reproach myself. I was just tired, pale, and I dropped off from time to time.

We stopped in Kraków. At midnight I was standing sentry on the rails. Over me sparkled innumerable pallid stars. A yellow moon appeared between loose clouds, turned a deep orange, and sank in a gory red. Barely a signal, barely a faraway light shone to me in the dark. I shivered, and my eyes were dropping shut.

We traveled onward.

In the morning we reached Jaroslaw, the new frontier town on the San. We piled out.

September sun lay on the platform of the little station. The Russian Empire began on the far side of the river… I sat down on a stack of boards, felt the warm sun in a tired way, and watched Russian POWs at work. Bearded faces, unkempt hair, empty eyes, and ripped uniforms all presented an image of sorry homelessness. Every movement that was performed was dull and slothful, and the guards swore and hit out with sticks and rifle butts. I felt no anger at the ill-treatment of these helpless men, and no sympathy either. I saw only their laziness and their obstinacy; I didn’t know yet that they were hungry. I was glad we had stopped moving for the moment and that we had another interval of time. I was completely preoccupied with my own destiny…

We picked up our knapsacks and marched to the barracks. Ocher houses with lofty windows behind dusty trees were redolent of an atmosphere of soldiery, service, and ugliness. We moved into bleak little rooms, with cockroaches, dust, and hunger. There our shared privation and distance from home made us into comrades. Secretly, though, everyone remained isolated. There were no bridges from one man to the next.

We marched out every day. With knapsack, coat, and blanket roll, with storm pack, bread sack, and rifle. Singing, we marched through Jaroslaw and followed the tarred roads into the outlying woods and hills. With singing and humor we battled through our exhaustion. We had to practice marching because at the time that was the only task we expected to be given during this war. We marched in rain and shine, and thunderstorms broke over our heads. We draped canvas sheeting about us, the wet dripped off our helmets, and our rifles sprouted rust like fungus.

I didn’t often go into town in the evenings. It wasn’t that it was strange to me, the towns of this world aren’t so very different, and at that time I didn’t have much of an eye for fine distinctions. It was a wretched caricature of a small town in Germany, without any amenities except a little library and a tolerable schnapps in some of the bars. I didn’t enjoy being a soldier among a conquered people. I felt strange and excluded; I felt ashamed of my presence there and often felt responsible for the people’s misery, as when an unmerited hatred seemed to strike at me from all directions. I bought cake and fruit to supplement the sparse diet, sometimes played the piano or read in the soldiers’ quarters, where we had a wildly varied selection at our disposal; then I would return home at night with my companions through the darkened town. We sat in smoky bars and drank the garish and syrupy schnapps. Later on we would stare at girls and women, but there were no encounters. I wasn’t immune to the tender blond or Gypsyish charms of Polish women, but I was too ashamed to go after love in the midst of this foreign people, and the squalid brothels only disgusted me. Eros took other paths, in our jokes, and everyone who told stories became his own Don Juan or Casanova. Only self-restraint and collective living could master what lay ahead of us. And so we lived like monks.

Usually I was on my own in the barracks reading room, and I wrote my letters, aphorisms, and poems and tried my hand at eerie tales. From my fables and fantasies I increasingly withdrew to philosophy and problems. Often serious conversations would go on till deep in the night. We were looking for some principle or backbone to help us bear our fate.

Every day the tormenting emptiness within me deepened, like the grief of a homesick child, while at the same time I ate the bread of what was to come and painted frescoes of my future.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «A Stranger to Myself»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «A Stranger to Myself» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «A Stranger to Myself» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.