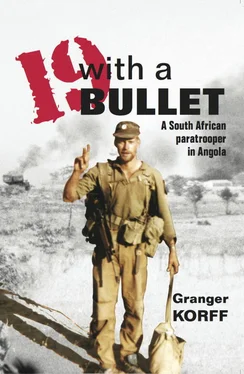

So here we were—a group of sweating, skinny, filthy men trudging through the harsh bush and thick sand of the Caprivi Strip and trying to hold on to the very tiny part of our brain that pushed us on, one step after another, to the next rendezvous point 25 kilometres away, knowing that we would simply be sent back again when we arrived. It was one of the toughest selection courses in the world. (Recces’ equivalent would perhaps be the United States Navy SEALs who, as far as I understood, did not spend seven weeks of their selection course walking 700 kilometres with next to no food.) The first phase of the selection process was a nine-week PT course, which we were spared because we had already gone through the gruelling PT course at 1 Parachute Battalion.

When the six of us paratroopers arrived at the infamous Bluff in Durban (1 Reconnaissance Commando’s base was on a large bluff, concealed by trees overlooking the sea), it was at the end of the nine-week PT course. We watched as straggling lines of dead-beat troops came in from kayaking around the bay and were now running with their kayaks on their shoulders. We climbed down from the trucks and felt awed standing in the legendary 1 Recce base camp, but were quickly hustled off to our quarters overlooking the sea. We had arrived just in time to be shipped off in trucks to Zululand for the second phase of the selection course, bush orientation.

It began with not being fed throughout the day-long drive to Zululand—a wilderness area a day’s ride north of Durban. When we arrived in the middle of the night, we immediately set out on a 25-kilometre route march. This sort of thing went on for two weeks.

Zululand is humid and subtropical. It was beautiful and lush on the coast, so we were able to get an occasional green wild banana or some maize meal from the local people who lived in scattered villages. We had to cross high mountains on our route marches, and would walk for miles on the long, deserted beaches carrying telephone poles. It was fun at the beginning to get away from 1 Parachute Battalion and all the bullshit. At least we were in the bush, sleeping in the dirt and walking all day covered with ‘Black is Beautiful’, a thick black grease that is used as camouflage cream—but after two weeks of marching 15 to 25 kilometres a day with little or no food, the adventure began to pall. One of the paratroopers, a senior bloke we didn’t know well, got lost. They had to send a spotter plane to find him.

The two weeks in Zululand weren’t that bad; only when all 200 of us volunteers left Zululand in a C-130 and flew thousands of miles north up to the Caprivi Strip for the third phase, did the shit really start.

The Caprivi is a piece of beautiful South West African bush that stretches in a long finger between Zambia and Botswana. It has tall trees and scattered evergreen scrub grows everywhere. At the start of the border war it had been a hot spot for SWAPO infiltration from Zambia but when Zambia lost interest in the ‘cause’ it became inactive, but it was still a ‘red area’—ideal for a Recce selection course. It is usually very hot and dry but it was the rainy season and the tough thorn and big mopane trees were thick with green leaves while the bush teemed with game.

Sightings, spoor and brushes with buffalo, wild dog, hyena, elephant and lion would be fairly common, as we were to find out in our hundreds of kilometres of meandering. Rainy season or not, when we climbed off the C-130 onto a small landing strip in the bush, the heat hit us like a wall. The glare from the white sand was intense and we were greeted by rough-looking black and white Reconnaissance troops dressed in terrorist camo and holding strange machine guns.

“This looks menacing,” I thought. “These guys look like they live in the bush.”

We were strip-searched and all hidden watches, cigarettes or anything that could make life easier in the bush was taken away. We were then divided into six- or seven-man teams, given a compass and a compass bearing and told to start walking through the bush to the rendezvous 20 ‘clicks’ (kilometres) away.

We walked and walked and walked. Then we walked some more. Day in and day out. Through nights, days, and nights again. We walked for five more weeks, 20 to 30 clicks every day, through the African bush.

No mad PT to fuck you up like there had been at 1 Parachute Battalion, just trudging through the Caprivi bush day after day, week after week, for 500 kilometres, until my brain screamed “No more!”

I pushed on.

My stomach shrunk to nothing, so did my body fat. We now had one meal every five days. We were given three cans of food and a loaf of bread to share between two guys every five days. And, every day, relentlessly, without flagging, another 20 or 30 kilometres. No nutrients; zero energy. Day after day. I had no idea that walking could be such prolonged torture. And now they gave us 60-millimetre mortar cases filled with cement to carry in our kit.

My mind started to play games with me. Some days I felt okay, gripped my mind and pushed on, step by step, but the next day I was depleted and could hardly move or think properly.

“Fuck this… I can’t carry on… no, carry on, you can do it… I can’t go on. I’m stopping at the tree! Carry on, boy… go past the tree and keep on… don’t stop now!”

It became a second-by-second mind-fuck.

We were a mixed bunch, but most of our course mates were older Permanent Force personnel with rank. Their rank was meaningless on this course and we spoke on an equal basis to sergeants, lieutenants and captains. Some were civilians who had finished their military service and had come back to try out for the Recces, like the skinny blond-haired bus driver who ended up coming first out of everybody on the course. There was Jan Muis, a huge bull of a man with bright blue eyes and a big walrus moustache, whose quiet manner kept us going. He had come from Civvy Street after his brother, a Recce apparently equally as big, was killed on a mission deep in Angola. The story was that he had taken 12 AK-47 rounds before he went down, taking a handful of SWAPO with him. Everyone had their own reasons for wanting to become a Recce. I was running out of reasons.

We had all lost weight dramatically; our filthy, torn uniforms hung on our skinny bodies. We had not shaved, washed or had a change of clothes since we had left the Bluff, which had been almost seven weeks before. We were filthy from the black camouflage grease that we had to put on every so often.

My stomach had long since shrunk so much that I wasn’t even that hungry any more, and had passed fantasizing about juicy hamburgers and huge, sizzling steaks. But the longing for an ice-cold Coke was ever present.

After well over a month now of constant walking and little food, I was having a hard time holding onto my mind and had lost the ability to judge distance and time. We had stopped quarrelling among ourselves over teamwork and now just walked in long silence, a line of six men spread over the space of half a kilometre, walking on each other’s spoor.

Hyenas constantly followed us in the distance; at night they would come right up among us hoping to take a chance bite of a carelessly exposed limb or skull. We slept like the spokes of a wagon-wheel, around a tree with our heads against the tree and our feet sticking out. Wild dogs would also be yapping in hunting packs close by, but they never bothered us.

We had reached a rendezvous point; it was feeding day and John Delaney and I were sitting under a large tree wolfing down our weekly three cans of beans. The instructors told us that ‘another paratrooper’ had been attacked and mauled by a lioness but was alright, and was continuing on the course with a few scratches. The lioness had crept up to him as he settled down to sleep. She had jumped him but quickly took fright and ran off when the other troops yelled at her in unison. We laughed, because it was Hans, and we knew that he would have a long story to tell when we met up with him again.

Читать дальше