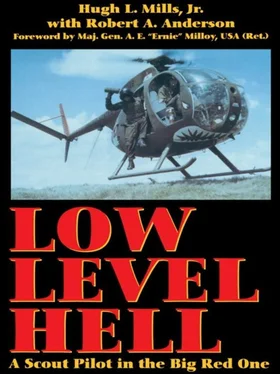

Hugh L. Mills, Jr.

with Robert A. Anderson

LOW LEVEL HELL

A SCOUT PILOT IN THE BIG RED ONE

This book is dedicated to the memory of the officers, noncommissioned officers, and troopers who died on the field of battle with Darkhorse in 1969. May they rest in peace.

WOl James K. Ameigh, aeroscout pilot, 24 June.

PFC William J. Brown, aerorifleman, 17 November.

SGT Allen H. Caldwell, aerorifleman, 17 November.

SP5 James L. Downing, aeroscout gunner, 6 November.

SP4 August F. Hamilton, aerorifleman, 28 July.

SP4 Eric T. Harshberger, aerolift crew chief, 1 November.

PFC Michael H. Lawhon, aerorifleman, 11 August.

SSG James R. Potter, aeroscout gunner, 11 September

1LT Bruce S. Gibson, aeroscout pilot, 11 September

SP4 James A. Slater, aeroscout gunner, 24 June.

WOl Henry J. Vad, aeroscout pilot, 6 November.

SGT James R. Woods, aerorifleman, 11 August.

Ever since man began to create military forces, the role of the military scout has been an extremely dangerous one. Working out in front of friendly forces, he has been exposed continually to the enemy—the first to make contact, and usually outgunned and outnumbered.

During the settlement of our country the scouts along the frontier laid their lives on the line daily. They played a major role in our development and are some of the true heroes of the times.

With the advent of the balloon in the middle of the last century, aerial reconnaissance was born. Scouts in the Civil War observed enemy activities from these lofty perches. Then came the manned airplane, and the drone airplane followed.

When the helicopter was introduced to the military inventory in the mid-twentieth century, the aeroscout technique was developed. It came into its own in the Vietnam War. Without taking anything away from the exploits of those brave men who gained fame in the early stages of our country’s development, men such as Davy Crockett, Kit Carson, and Jim Bowie, the aeroscout achieved an effectiveness far superior to that of his forebears. Also, his exposure to the enemy was increased manyfold. Long hours of daily exposure to heavy ground fire, in often-marginal weather and over treacherous terrain, served to test the mettle of these brave young men.

This book is an account of one man’s experiences in the Vietnam War as an aeroscout pilot. Hugh Mills is eminently qualified to write such a story. He served two tours in Vietnam as an aeroscout pilot and was instrumental in developing many of the tactics and techniques employed by the aeroscouts, as well as improving upon some of the original concepts. During that time he was shot down sixteen times, wounded three times, and earned numerous decorations for valor, including three Silver Stars, four Distinguished Flying Crosses, and three Bronze Stars with V devices. He knows whereof he speaks.

On my second tour in Vietnam it was my good fortune to be assigned as commander of the First Infantry Division, The Big Red One. Early on, the aeroscouts came to my attention. An extraordinary amount of enemy information being received at division headquarters came from this small unit. Naturally, I was somewhat skeptical. Compared with the volume and detail furnished by other intelligence-gathering agencies, it appeared that the aeroscouts might be overly imaginative. Accordingly, I set out to determine just who was doing what. I frequently over-flew aeroscout operations and monitored their communications from my command-and-control helicopter. It was quickly evident that these hardy souls were reliable, expert, and, above all, very brave. They were furnishing the lion’s share of intelligence information because they had the knowledge, the will, and the guts to go out and get it.

During the monsoon season they flew at times when even the native ducks were grounded. When they suspected enemy presence but could not observe any signs, they deliberately and routinely exposed themselves to hostile fire by dropping through “holes” in the jungle canopy to hover at ground level and look under the trees. They invited someone to shoot at them. Anyone who has heard the snap of bullets flying by his head, or has experienced the shattering sound of enemy fire slamming into the fuselage of an aircraft, can appreciate the kind of courage it takes to invite such action.

The point to be made here is that although this book may appear to be a novel with historical background, it is not. Neither is it a self-serving attempt on the part of Hugh Mills to appear as a hero. It is a factual account of a group of extraordinarily valiant young men who fought as aeroscouts in the Vietnam War. All who read it should be extremely grateful to them.

A. E. Milloy Major General, U.S. Army, Retired

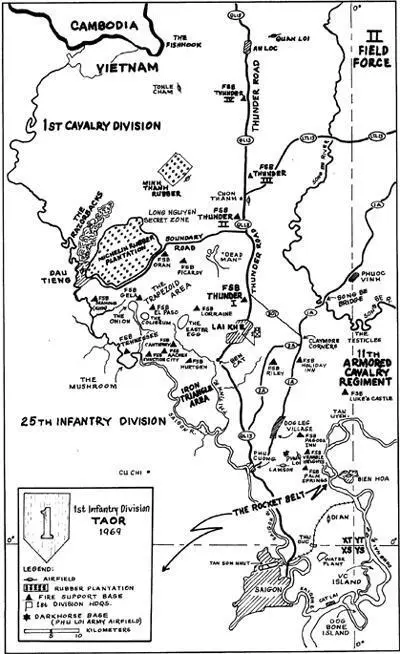

South Vietnam, July 1969

“Phu Loi tower, this is Darkhorse One Six. I’ve got a hunter-killer team on the cav pad. North departure to Lai Khe.”

“Roger, Darkhorse One Six flight of two. You’re cleared to hover.”

Cobra pilot Dean Sinor (Three One) and I were heading up to Thunder Road to provide aerial cover to a heavy northbound supply convoy. A scout and gun team ran ahead of convoys coming out of Lai Khe to run a low-level inspection of the entire road up to An Loc. Even though dismounted engineer and infantry swept the highway for mines every morning at first light, this stretch of road had proved highly susceptible to ambush attack.

With Sinor at altitude, I put my Loach down low and slow, to pick up anything out of place on or along the road. It was possible for the enemy to get in and plant a few mines between the time it was swept by the engineers and the arrival of the convoy. Early in the morning, once the highway had been swept by the engineers, civilian traffic was always bustling along Thunder Road—motorcycles, mopeds, carts, Cushman-type vehicles, little buses, and small trucks. But never before the U.S. Army had cleared the road for mines. It was far too dangerous.

Working about a mile ahead of the convoy, I headed straight down the highway, banked to the east, then back south to check the cleared area on the column’s right flank. I cut west over the last vehicle and headed back north to check out the left side of the convoy, creating a boxlike search pattern.

On my first run back along the east side of the road, I saw evidence of recent heavy foot traffic, enough to make me feel very uneasy. I didn’t see any enemy, so I headed across the tail end of the convoy to make my run back north on the west flank.

As I got about six hundred yards out ahead of the column, I picked up heavy foot trails again. There wasn’t any good reason for people to have been out in the Rome-plowed area next to the highway, so I decided to follow one of the trails to see where it took me. It led to a drainage ditch that stretched for nearly a mile—right along the side of the highway! But, again, not a single person in sight.

Circling over the area, I keyed the intercom to my crew chief. “Parker, do you see anything? Something’s damned screwy about this. What do you make of it?”

“Don’t see anything but footprints, Lieutenant. Not a soul, sir!”

About that time I made a sharp turn over a thick clump of tall grass on the west side of the road near the drainage ditch, about ten feet from the side of the highway. Not more than four to five feet below me, I glimpsed a slight movement and something dark lying on the ground.

Читать дальше