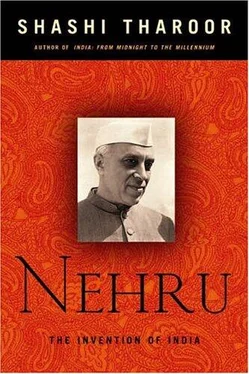

Tharoor Shashi - Nehru - The Invention of India

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Tharoor Shashi - Nehru - The Invention of India» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2004, Издательство: Arcade Publishing, Жанр: Биографии и Мемуары, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Nehru: The Invention of India

- Автор:

- Издательство:Arcade Publishing

- Жанр:

- Год:2004

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Nehru: The Invention of India: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Nehru: The Invention of India»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Nehru: The Invention of India — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Nehru: The Invention of India», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

The general elections legitimized Congress rule and Jawaharlal Nehru’s prime ministership of India. It was an India whose internal political contours he would soon have to change. During the nationalist movement the Congress had affirmed the principle of linguistic states, arguing that language was the only viable basis for India’s political geography. But partition shocked Nehru (and Patel) into rejecting any proposal to redraw state boundaries, for fear of accelerating any latent fissiparous tendencies in the country. So independent India’s provincial boundaries remained drawn for administrative convenience until a southern Gandhian, Potti Sriramulu, undertook a fast-unto-death for the creation of a Telugu-speaking Andhra state — and, after fifty-five days of fasting, actually died. Protests erupted throughout the Telugu-speaking districts of Madras, and Nehru gave in. Andhra Pradesh was created and a States’ Reorganization Commission appointed, whose recommendation in 1955 to redraw India’s internal boundaries along mainly linguistic lines was largely implemented the following year.

Meanwhile, Jawaharlal saw in his 1952 electoral victory an affirmation of popular support for the principles of socialism and anti-imperialism that he had begun articulating publicly in the 1936 campaign. Though not formally a Marxist, Jawaharlal had revealed a susceptibility to Marxian analyses of historical forces in his early writings. In an unfinished review of Bertrand Russell’s 1918 book Roads to Freedom Nehru had already laid out the basics of his political philosophy. “Present-day democracy,” he wrote (in 1919), “manipulated by the unholy alliance of capital, property, militarism and an overgrown bureaucracy, and assisted by a capitalist press, has proved a delusion and a snare.” But “Orthodox Socialism does not give us much hope…. [A]n all-powerful state is no lover of individual liberty…. Life under Socialism would be a joyless and soulless thing, regulated to the minutest detail by rules and orders.” At the Lucknow Congress in 1936 Nehru had gone further, declaring: “I am convinced that the only key to the solution of the world’s problems and of India’s problems lies in socialism…. I see no way of ending the poverty, the vast unemployment, the degradation and the subjection of the Indian people except through socialism. That involves vast and revolutionary changes in our political and social structure, … a new civilization radically different from the present capitalist order. Some glimpse we can have of this new civilization in the territories of the USSR…. If the future is full of hope it is largely because of Soviet Russia.”

But he came to temper that view: Nehru was too much of a Gandhian to be a fellow-traveler of the Soviet Union, though he shared the admiration for the triumphs of the 1917 Revolution commonly felt by leftists of his generation. But he always put nationalism before ideology: convinced that the Communists’ loyalties were extraterritorial, he demanded of a band of Communists waving their hammer-and-sickle banner during the 1952 campaign, “Why don’t you go and live in the country whose flag you are carrying?” (They replied, in staggering ignorance of their critic: “Why don’t you go to New York and live with the Wall Street imperialists?”)

Jawaharlal’s constant search for the politically viable middle had kept him at the head of the eclectic Congress Party rather than led him to the ranks of his ideological soulmates, the Socialists. Nehruvian socialism was a curious amalgam of idealism (of a particularly English Fabian variety), a passionate if somewhat romanticized concern for the struggling masses (derived from his own increasingly imperial travels amid them), a Gandhian faith in self-reliance (learned at the spinning wheel and typified by the ostentatious wearing of khadi), a corollary distrust of Western capital (flowing from his elemental anticolonialism), and a “modern” belief in “scientific” methods like Planning (the capital letter is deliberate: Nehru elevated the technique to a dogma).

This idiosyncratic variant of socialism became an increasing hallmark of his rule. Jawaharlal saw Indian capitalism as weak and concentrated in a few hands; to him the state was the only guarantor of the economic welfare of ordinary people. Some degree of planning was probably unavoidable; even the Bombay business community drew up a plan in 1944 for India’s rapid industrialization. There was certainly a need for the state to invest some resources where the private sector would not, particularly in infrastructure and in agriculture. The economist Jagdish Bhagwati has suggested that what India needed at the time was probably socialism on the land and capitalism in industry. Nehru tried the opposite. Despite Patel’s skepticism, Nehru prompted the government of India to adopt an Industrial Policy Resolution in April 1948 that granted the state monopolies over railways, atomic energy, and defense manufacturing as well as reserved rights relating to any new enterprise in a host of vital areas, from coal and steel to shipbuilding and communications. The Constitution that came into force on January 29, 1950 included a section on the “Directive Principles of State Policy” which enshrined socialist goals but made them objectives, not enforceable rights. In 1950 the government of India created a permanent Planning Commission with Jawaharlal Nehru as chairman.

The result was to embark the nation upon a series of Five-Year Plans, starting in 1952, that bore successively decreasing relation to reality; actively impeded, rather than facilitated, the country’s development; and shackled India to what became derisively known in economic circles as “the Hindu rate of growth” (a fitful 3 percent when the rest of the developing countries of Asia were racing along at 10 to 12 percent or better). Nehru’s mistrust of foreign capital kept out much-needed foreign investment but paradoxically made India more dependent on foreign aid. This applied not just to industry: the First Plan’s necessary emphasis on agriculture (essential following the loss of the “national granary,” West Punjab, to Pakistan) was so faulty in conception that by 1957 the country’s agricultural output had dropped below that of 1953 and the government was soon importing food grains in a country where four out of five Indians scratched their living from the land.

Nehru’s economic assumptions demonstrated that one of the lessons history teaches is that history often teaches the wrong lessons: since the East India Company had come to trade and stayed on to rule, Nehru was instinctively suspicious of every foreign businessman, seeing in every Western briefcase the thin end of a neo-imperial wedge. The Gandhian equation of political nationalism with economic self-sufficiency only served to underscore Nehru’s prejudice against capitalism, which (far from being synonymous with freedom) was in his mind equated principally with the slavery of his people. Protectionism was the inevitable result: in Jawaharlal’s mindset the essential corollary of political independence was economic independence. That this meant a far slower release from poverty for the Indian people he never understood.

There followed the inaptly named Industries (Development and Regulation) Act of 1951, which entrenched regulation and strangled development, and a series of similarly wrongheaded laws that enshrined what Rajaji called the “license-permit-quota Raj.” The road to disaster was, as usual, paved with good, even noble, intentions. In December 1954 the government, under Jawaharlal’s prodding, formally adopted the goal of “a socialistic pattern of society,” and the Congress resolved at Avadi the next year to place the state on the “commanding heights” of the national economy. Within a year the Second Five-Year Plan enshrined industrial self-sufficiency as the goal, to be attained by a state-controlled public sector which would dominate the “commanding heights” of the economy. This public sector would be financed by higher income, wealth, and sales taxes on India’s citizenry. India would industrialize, Indians would pay for it, and the Indian government would run the show. This approach was formalized in an Industrial Policy Resolution in 1956 that enshrined state capitalism in India while calling it socialism. Nehru placed bureaucrats rather than entrepreneurs upon the commanding heights, stifled initiative and investment, and spent the rest of his rule presiding over a system that sought to regulate stagnation and divide poverty.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Nehru: The Invention of India»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Nehru: The Invention of India» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Nehru: The Invention of India» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.