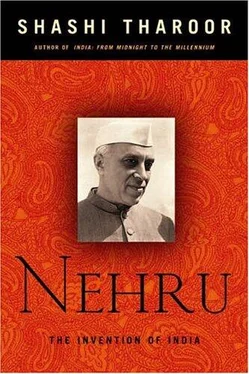

Tharoor Shashi - Nehru - The Invention of India

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Tharoor Shashi - Nehru - The Invention of India» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2004, Издательство: Arcade Publishing, Жанр: Биографии и Мемуары, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Nehru: The Invention of India

- Автор:

- Издательство:Arcade Publishing

- Жанр:

- Год:2004

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Nehru: The Invention of India: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Nehru: The Invention of India»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Nehru: The Invention of India — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Nehru: The Invention of India», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

Jawaharlal’s approach to the economy was in many ways characteristic of the great flaw that afflicted many freedom fighters: the experience of exclusion and prison gave them an excessively theoretical notion of governance, while nationalist passions injected mistrust of foreigners into policy. Public-sector ventures were run like government departments, overstaffed by bureaucrats with no commitment to their products and no understanding of business. Of course, some good came of Nehru’s bad economics: above all, the establishment of a norm of peaceful social change, eschewing both the violence from above favored by the Communists and the laissez-faire conservatism of the landed zamindars and commercial interests. Some would point also to the development of India’s industrial and intellectual infrastructure — the dams, steel mills, and institutes of technology that are the most visible result of Jawaharlal’s leadership of India’s economic policy. Yet others could argue both that these could have come through the private sector and that most of India’s public-sector industries were so inefficient that the country would actually have been better off without them. (Certainly the most successful steel plant in India was one set up in the private sector by the Tatas — under British rule.)

Jawaharlal bore a great deal of personal responsibility for the follies of planning, since it was not only led and directed by him in pursuit of his own convictions, but was conducted in a manner that discouraged dissent. All too often, opposition to planning was made to seem like opposition to a fundamental national interest and disloyalty to Jawaharlal himself. Under Nehru, socialism (as he practiced it) became a national dogma, to which his successors stayed loyal long after other developing countries, realizing the folly of his ways, had adopted a different path. Rajaji abandoned him to establish the Swatantra (Independence) Party in 1959 explicitly in protest against Nehru’s economic policies, but his was the only dissent from what became a national consensus, and the Swatantra, a pro — free enterprise, pro-Western, conservative party, never acquired enough support to mount a serious challenge to Nehruvian dominance.

The fact was that, following Patel’s death, Nehru had progressively turned into a leader without equal and without a rival. Having ousted Tandon and taken on the party presidency himself in 1951, Jawaharlal felt confident enough of his power within three years to relinquish it again. An unthreatening veteran, U. N. Dhebar, was chosen to replace him from January 1955, not by a full ballot of the All-India Congress Committee as in the past, but by the Congress Working Committee under Nehru’s chairmanship — a throwback to the days when that body simply rubber-stamped the Mahatma’s nominee for president. If some thought that Jawaharlal had become the uncrowned king of the Congress, the adjective was soon remedied by a fifty-year-old Tamilian woman who came up to him unbidden (at the very session in which he gave up his presidency) and placed a golden crown on his balding head. (She then turned to the audience and announced that Jawaharlal was a modern Lord Krishna, confusing the symbols of monarchy with those of mythology.) Nehru promptly handed the crown to Dhebar and asked him to sell it off to benefit the party’s coffers. But that minor moment of embarrassment epitomized a reality that Jawaharlal implicitly understood and never exploited.

At least not to the hilt. He could have used the adulation of the masses to turn himself into the dictator his own Modern Review article had suggested he might become. It was, indeed, the way most nationalist leaders in developing countries had gone. “Every conceivable argument has been available to tempt Mr. Nehru to forego democratic institutions in India,” the philosopher Bertrand Russell wrote. “Illiteracy and poverty, disease and ignorance, a great subcontinent to govern, severe differences between Muslim and Hindu, many scores of languages and varied cultures reflecting a tendency toward a breaking up of the Union.” Nehru rejected all these arguments.

Instead he went out of his way to demonstrate respect for the institutions of the state, showing due deference to the president as head of state (and even to the vice president, who had little to do but also outranked the prime minister in protocol terms). He treated Parliament as a serious and august body to which he was accountable, and ensured that his officials treated it as more than a forum for launching policy, but one whose demands and questions had to be treated with due deference. He set the example himself, spending hours in Parliament, suffering Prime Minister’s Question Time, and responding seriously to queries unworthy of his attention. He wrote regular monthly letters to the chief ministers of the provinces (later states) to share national and international concerns with them and consult them on issues of policy. He was astonishingly accessible to supplicants and complainants alike. As he explained,

It is perfectly true that I make myself accessible to every disgruntled element in India. That is my consistent practice. In fact, I go out of my way … [to be] accessible to everyone, time permitting. I propose to continue this because that is the way I control these people and, if I may say so, to some extent, India.

During the 1952 elections, when enthusiastic crowds shouted, “Pandit Nehru zindabad” (“Long live Pandit Nehru”), he would urge them to shout instead, “Naya Hindustan zindabad” (“Long live the new India”) or simply “Jai Hind” (“Victory to India”). When challenged on fundamental issues of policy his instinct was to offer his resignation: this instantly brought his critics around, but it was not the gesture of a Caesar. It revealed him to be both a democrat and a statesman conscious of his own indispensability.

Indispensable he was. In 1956 the cartoonist R. K. Laxman depicted Nehru playing several instruments simultaneously — a tabla with his right hand, a French horn with his left, a sitar propped up against a shoulder and a pair of cymbals at his feet, and even a party tooter in his mouth — as his audience of Congress stalwarts dutifully marked time. The instruments were labeled “financial affairs,” “foreign affairs,” “domestic affairs,” “Congress affairs,” and “SRC affairs” (for the States’ Reorganization Commission). Laxman titled his cartoon “The show must go on.” No one doubted the polyphonic excellence of the virtuoso performer.

World affairs had always been Jawaharlal’s favorite subject, and from the days when he drafted resolutions on international affairs for the annual sessions of the Congress, he enjoyed an unchallenged standing in the country as the maker and enunciator of policy. He carried this on into his prime ministership, retaining the External Affairs portfolio for himself. In one analyst’s words, “Nehru’s policies were India’s, and vice-versa.” (Indeed, for all practical purposes, India had no foreign policy, but Nehru did: senior Indian diplomats sometimes learned of policy from Nehru’s extempore speeches in Parliament.) This also meant that areas in which Jawaharlal was not particularly interested — geographically (Southeast Asia, Latin America, Africa) or substantively (international commerce and trade relations, defense and security policy) — were largely ignored. Diplomats conducted themselves in his image, focusing on policy, pronouncement, and protocol in the assertion of India’s nationhood rather than seeing foreign policy as a means of bringing economic and security benefits to the newly independent country. Given Jawaharlal’s extraordinary personal stature, no one dared challenge him; a few who did, early on, were given a taste of the prime minister’s temper, and learned quickly to acquiesce in whatever Nehru wanted. As a result, Indian foreign policy emerged whole from the head and heart of one man.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Nehru: The Invention of India»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Nehru: The Invention of India» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Nehru: The Invention of India» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.