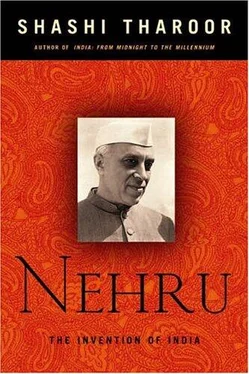

Tharoor Shashi - Nehru - The Invention of India

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Tharoor Shashi - Nehru - The Invention of India» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2004, Издательство: Arcade Publishing, Жанр: Биографии и Мемуары, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Nehru: The Invention of India

- Автор:

- Издательство:Arcade Publishing

- Жанр:

- Год:2004

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Nehru: The Invention of India: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Nehru: The Invention of India»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Nehru: The Invention of India — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Nehru: The Invention of India», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

The man who, as Congress president in Lahore in 1929, had first demanded purna swaraj (full independence), now stood ready to claim it, even if the city in which he had moved his famous resolution was no longer to be part of the newly free country. Amid the rioting and carnage that consumed large sections of northern India, Jawaharlal Nehru found the time to ensure that no pettiness marred the moment: he dropped the formal lowering of the Union Jack from the independence ceremony in order not to hurt British sensibilities. The Indian tricolor was raised just before sunset, and as it fluttered up the flagpole a late-monsoon rainbow emerged behind it, a glittering tribute from the heavens. Just before midnight, Jawaharlal Nehru rose in the Constituent Assembly to deliver the most famous speech ever made by an Indian:

Long years ago we made a tryst with destiny, and now the time comes when we shall redeem our pledge, not wholly or in full measure, but very substantially. At the stroke of the midnight hour, when the world sleeps, India will awake to life and freedom. A moment comes, which comes but rarely in history, when we step out from the old to the new, when an age ends, and when the soul of a nation long suppressed finds utterance.

“This is no time … for ill-will or blaming others,” he added. “We have to build the noble mansion of free India where all her children may dwell.” And typically he ended this immortal passage with a sentence that combined both humility and ambition, looking beyond the tragedy besieging his moment of triumph to India’s larger place in the world: “It is fitting,” he said, “that at this solemn moment we take the pledge of dedication to the service of India and her people and to the still larger cause of humanity.”

There would be challenges enough ahead, but Jawaharlal Nehru would never cease, even at the moment of his greatest victory, to look above the suffering around him and fix his gaze upon a distant dream.

7 V. K. Krishna Menon, an acerbic south Indian intellectual and longtime London resident, had helped publish Jawaharlal in England and led the pro-Congress India League since 1929. Jawaharlal met Menon for the first time in London in 1935 and was greatly impressed with his intelligence, his energy, and his left-wing credentials, but observed: “he has the virtues and failings of the intellectual.” Their friendship was deep, abiding, and, as we shall see, ultimately ill-starred.

8.“Commanding Heights”: 1947–1957

One man did not join the celebrations that midnight. Mahatma Gandhi stayed in Calcutta, fasting, striving to keep the peace in a city that just a year earlier had been ravaged by killing. He saw no cause for celebration. Instead of the cheers of rejoicing, he heard the cries of the women ripped open in the internecine frenzy; instead of the slogans of freedom, he heard the shouts of the crazed assaulters firing their weapons at helpless refugees, and the silence of trains arriving full of corpses massacred on their journey; instead of the dawn of Jawaharlal’s promise, he saw only the long dark night of horror that was breaking his country in two. In his own Independence Day message to the nation Jawaharlal could not help thinking of the Mahatma:

On this day, our first thoughts go to the architect of freedom, the Father of our Nation who, embodying the old spirit of India, held aloft the torch…. We have often been unworthy followers of his, and we have strayed from his message, but not only we, but the succeeding generations, will remember his message and bear the imprint in their hearts.

It was a repudiation as well as a tribute: the Mahatma was now gently relegated to the “old spirit of India” from whom the custodians of the new had “strayed.” In his crushing disillusionment with his own people (of all religions), the Mahatma announced that he would spend the rest of his years in Pakistan, a prospect that made the leaders of the League collectively choke. But he never got there: on January 30, 1948, a Hindu extremist angered by Gandhi’s sympathy for Muslims shot him dead after a prayer meeting. Mahatma Gandhi died with the name of God on his lips.

The grieving nation found grim solace only in the fact that his assassin had been a Hindu, not a Muslim; the retaliatory rage that a Muslim killer would have provoked against his coreligionists would have made the partition riots look like a school-yard brawl. “The light has gone out of our lives,” a brokenhearted Jawaharlal declared in a moving broadcast to the nation, “and there is darkness everywhere. . The light has gone out, I said, and yet I was wrong…. For that light represented something more than the immediate present; it represented the living truth, the eternal truths, reminding us of the right path, drawing us from error, taking this ancient country to freedom.” Jawaharlal Nehru had lost a father figure; after Motilal’s death he had grown at the feet of the Mahatma, relying on the older man’s wisdom, advice, and patronage. Now, at the age of fifty-eight, he was truly alone.

The first months of independence were anything but easy. Often emotional, Jawaharlal was caught up in the human drama of the times. He was seen weeping at the sight of a victim one day, and erupting in rage at a would-be assailant hours later. Friends thought his physical health would be in danger as he stormed from city to village, ordering his personal bodyguards to shoot any Hindu who might attack a Muslim, providing refuge in his own home in Delhi for Muslims terrified for their lives, giving employment to young refugees who had lost everything. The American editor Norman Cousins recounted how one night in August Hindu rioters in New Delhi, “inflamed by stories of Moslem terror … smashed their way into Moslem stores, destroying and looting and ready to kill”:

Even before the police arrived in force, Jawaharlal Nehru was on the scene …, trying to bring people to their senses. He spied a Moslem who had just been seized by Hindus. He interposed himself between the man and his attackers. Suddenly a cry went up: “Jawaharlal is here!” … It had a magical effect. People stood still…. Looted merchandise was dropped. The mob psychology disintegrated. By the time the police arrived people were dispersing. The riot was over…. The fact that Nehru had risked his life to save a single Moslem had a profound effect far beyond New Delhi. Many thousands of Moslems who had intended to flee to Pakistan now stayed in India, staking their lives on Nehru’s ability to protect them and assure them justice.

Affairs of state were just as draining. The new prime minister of India had to deal with the consequences of the carnage sweeping the country; preside over the integration of the princely states into the Indian Union; settle disputes with Pakistan on issues involving the division of finances, of the army, and of territory; cope with massive internal displacement, as refugees thronged Delhi and other cities; keep a fractious and divided nation together; and define both a national and an international agenda. On all issues but that of foreign policy, he relied heavily on Patel, who welded the new country together with formidable political and administrative skills and a will of iron. A more surprising ally was the former viceroy, now governor-general of India, Lord Mountbatten.

For all his culpability in rushing India to an independence drenched in blood, Mountbatten made Nehru partial amends by staying on in India for just under a year. As heir to a British government whose sympathy for the League had helped it carve out a country from the collapse of the Raj, Mountbatten enjoyed a level of credibility with the rulers of Pakistan that no Indian governorgeneral could have had. This made him a viable and impartial interlocutor with both sides at a time of great tension. When fighting broke out over Kashmir between the two Dominions (whose armies were still each commanded by a British general), Mountbatten helped prevent a deeper engagement by the Pakistani army and brought about an end to the war. Equally, as a governor-general above the political fray, he played a crucial role in persuading maharajahs and nawabs distrustful of the socialist Nehru to accept that they had no choice but to merge their domains into the Indian Union. And the governor-general and his wife distinguished themselves by their personal interest in and leadership of the emergency relief measures that saved millions of desperate refugees from misery and worse. In 1950, when India became a republic with its own Constitution, Jawaharlal arranged for it to remain within the British Commonwealth, acknowledging the British sovereign no longer as head of state but as the symbol of the free association of nations who wished to retain a British connection. Mountbatten’s influence was decisive in prompting Jawaharlal to make this choice. Nehru’s close relations with Edwina Mountbatten have been the stuff of much posthumous gossip, but his relationship with her husband was to have the more lasting impact on India’s history.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Nehru: The Invention of India»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Nehru: The Invention of India» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Nehru: The Invention of India» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.