“Children, obey your parents in the Lord, for this is right. Ephesians 6:1. I love you Mom, I love you Dad.” —Kristin Chang

“I am crucified with Christ, therefore I no longer live. Jesus Christ now lives in me! — Embrace the Cross.” —Julie Cheng

Meanwhile, Brian’s lips are attached to his girlfriend’s, a fact I jealously espy, and mine are attached to a tallboy in a brown paper bag. Since I’ve started drinking, I’ve started drinking . Kahlúa and milk with Sara, Fifth Avenue rooftop screwdrivers with Alana, another girl I’m chastely in love with, vodka and tonic, vodka and grapefruit juice, vodka and vodka, pitchers of hard cider in the afternoon at the Life Café on the corner of Tenth and Avenue B. In true alcoholic fashion, I divide the day into quadrants of booze, the rise and fall of the sun regulated by clear and brown liquors. I’d tasted alcohol many years before Stuyvesant — I am from a Russian family, after all — but here with my outcast friends every twenty-four ounces’ worth carries me a little bit away from the dreams I can no longer fulfill. Because even as I’m chugging away in the Park, my mother is deep in the bowels of the Beaux-Arts Stuyvesant building, standing at the head of a long line of similarly teary Asian mothers, begging the physics teacher to pass me in her sweet but not fully there English, telling him, “My son, he has trouble to adjust.”

Booze. It sands away the edges. Or it makes me all edges. Take your pick. When I laugh now, I hear the laughter coming from far away, as if from another person. I hear that bright, crazy laughter of mine, and then I hear it submerged in the bright, crazy laughter of my colleagues, and I feel brotherhood. Ben! Brian! John! Other Guy! I do declare jihad on you!

Would it be outrageous to say that at this point in my life alcohol is the best thing to ever have happened to me?

Absolutely. It would be outrageous. Because there’s also pot.

In an attempt to help me deal with peer pressure Mama and the newly arrived Aunt Tanya have shown me how to smoke a cigarette and stream it quickly out of the right side of my mouth without really inhaling. The three of us stand in the backyard of our Little Neck house, fall leaves scrunching underfoot, fake smoking, and acting nonchalant like in the movies. “ Vot tak, Igoryochek ,” Mama says as I let the smoke spill out of my mouth, my nose hungering after its sweet, forbidden smell. That’s how it’s done, Little Igor. Now I can pretend to smoke cigarettes or pot just like the cool kids. I apply this knowledge to my first fifty or so encounters with the evil weed, pretending to be even more stoned than the rest of my friends, screaming my nonsense: “Peace in the Middle East! Gary out of the ghetto! No sellout!” But on the fifty-first time, somewhere at the beginning of junior year, I forget to exhale.

If alcohol obliterates me, the pot unpeels me. Down to the nub. The last 234 pages you have just read — they never happened. There was no Moscow Square, no Lenin and His Magical Goose , no Buck Rogers in the 25th Century , no “Gentlemen, we can rebuild him, we have the technology,” no Gnorah, no Mama, no Papa, no Lightman, no Church and the Helicopter. Down to the nub, as I’ve said. But what if the nub’s no good either?

And when the pot laughter comes out of me, it is slow and deliberate, starting from my toes and ending in my eyelashes. As it travels up my body, it tickles the nub, and it doesn’t matter whether the nub is good or bad, just that it’s there, stored away for future use.

How does one transition from Republican striver to absolute stoner? I will never be fully accepted into the crowd, much as I will never learn the words to Cream’s “Sunshine of Your Love.” If I’m lucky, I’m maybe invited to every third party, and the prettiest of the girls still keep their distance from me. But the “hippies,” as they’re called, are the closest I have to a group of friends. When I see carved into a rotting school desk the words “Fuck all Hippies, Gideon take a shower,” I feel angry at the author of such words and also a strange wish that I myself could smell that bad. If only I could be the opposite of what I was raised to be. If only I could be a fully natural being like this Gideon, whose father happens to be some kind of American genius at something and whose family lives in a sprawling West Village penthouse.

I love the boys, but Manhattan is my best friend. Walking down Second Avenue on a Friday night, I pass a man and woman in cheap tight clothes, standing in the middle of the sidewalk crying in each other’s arms. Crowds of teenagers gingerly walk around them, not exactly stunned by this display but respectful of the unabashed emotion. Everyone around me is silent for at least a block. I double back to take another look. The woman’s face is barely visible, but as she leans back I notice her slightly Persian cast, the parabola of her long lashes, her coarse red lips. She is beautiful. But so is everyone else. It is hard to walk from the Safe Train on Fourteenth Street to the school on Fifteenth without falling desperately in love.

This is what I’m learning. Men and women, in various combinations of gender, are exchanging small bits of sexual information with their eyes, then rounding the next corner as if they had never met. Yes , my eyes say to nearly every woman who passes, but they only scowl and avert their eyes ( No ) or smile and look away ( No, but thanks for thinking of me ). Finally, on a soupy summer day, a young woman walking ahead of me lowers her shorts so that the curve of her posterior is visible. She turns around and flashes a brief, gap-toothed smile. She starts to walk faster. I can barely keep up. There are now several men on her trail, most of them young professionals in suits, all of us silent and needy. Every few blocks, she lowers her shorts a bit more, bringing out little bellows of disbelief from her followers. Suddenly she runs across the street and disappears into a doorway, laughing at us before slamming the door. We look around to discover we are on Avenue D, in the shadow of some fierce-looking projects. This is the farthest I have been from Little Neck, and I am never going back.

The greatest lies of our childhood are about who will keep us safe. And here an entire city is coming together with its fat, ugly arms around me. And here, for all the talk of muggers and blade swingers, no one will hit me. Because if there is a religion here, it is the one we’ve made. Parents, obey thy children in the Lord, for this is right.

*Later, I will devote more than a decade to this task.

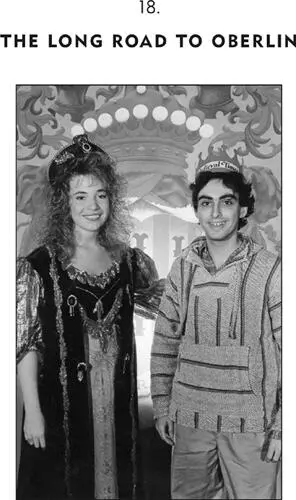

18. The Long Road to Oberlin

The author has been rightfully crowned the King of Medieval Times. To the left is his blushing queen.

BACK IN QUEENS, my parents sense that I’m going off the rails, but they’re actually quite nonviolent about it. My father patiently tries to diagram the workings of a combustion engine so that I may survive physics. My mother begs forgiveness from teachers on my behalf. Everything is being done to make sure I can recover grade-wise in time for law school. And while my mother is unhappy that I show up at three in the morning drunk—“Why, why didn’t you call us if you were going to be nine hours late?” “I ran out of quarters, Mama!”—my parents did both grow up in Russia and understand how young adult life works. On the few occasions when I return from a virginal night out with a girl, my father will take time out from slicing up one of his prized heirloom tomatoes at the kitchen table to query, “ Nu , are you a man yet?” He’ll lean in and smell the air around me. And I will sigh and say, “ Otstan’ ot menya ,” Leave me alone, and stomp, stomp, stomp upstairs to my Playboys and my Essays That Worked for Law School .

Читать дальше