The next day I pack two gigantic garbage bags with my summer clothes and my Isaac Asimovs . I tell my father to drive me to the Peter Pan bus station. I cannot remember most of the fight that takes place between me and my mother as I announce my leave-taking, except for the fact that she does not retreat one centimeter, does not even acknowledge that the Sauerkraut Arms is not the Hilton. “What’s the difference between the two?” she shouts. “Show me one difference!” It is a frightening fight, with my mother’s harshest words and her silent treatment somehow woven into one. But it’s an important fight, too. I stand my ground. I will not be lied to.

“I’d like to see you live alone at home!” my mother says. “I’d like to see you starve.”

“I have fifty-three dollars,” I say.

And so my father, my partner in this particular crime, wheels me over to the bus station with my two garbage bags full of clothes and books. He kisses me on both cheeks. He looks me in the eye. “Bud’ zdorov, synok,” he says. Be well, little son . And then a sly but respectful wink. He knows I have triumphed over her.

Only what have I done? The scenery is scrolling past me, the bridges and woods of New England giving way to the grilled-cheese patty-melt of a New York City summer. I am alone in the Peter Pan, surrounded by American adults and their Walkmans. All alone, but what else? Emancipated, liberated, giddy, with fifty-three dollars in allowance money to last me one and a half weeks.

At the Port Authority, I scramble past the subway turnstile with my two garbage bags. By the time I reach eastern Queens, two hours and many subway trains later, one of them breaks. (Our family is not the kind to use Hefty and other premier-class bags.) I try to tie off the hole in the bag with my hands, but you have to be very handy to do this successfully, and I am, no point denying it, a mama’s boy, unable to perform basic tasks. I take some of the clothes out of the distressed garbage bag and wear them in layers around me, tying several T-shirts around my neck. Not wanting to spend an extra token, I trudge the last segment to our garden apartment on foot, sweating for about five miles in the early summer heat beneath many layers of clothing as I drag my one and a half garbage bags behind me.

I run down to the Waldbaum’s supermarket and invest in forty dollars’ worth of Swanson Hungry-Man TV dinners, a half-dozen full-sized bags of Doritos, which my family never eats (my parents call them rvota , or “vomit”), and several fun-sized bottles of Coke. There isn’t a McDonald’s within striking distance, and I do not wish to try my luck with the Burger King, where I believe the basic hamburger is costlier and inauthentic.

Back home, I take my clothes off down to my underwear and turn on the television for 240 hours. Mama, what have I done to you? I cry as the morning news turns into the nightly news and a comic show about an inventive orphaned child named Punky Brewster takes up some of the time in between. How could I have run away from you like that? Am I really any better now than this motherless Punky?

My father calls from Cape Cod to check up on me.

“Could you put Mama on?” I ask.

“She doesn’t want to speak to you.”

And I know what will happen when she returns, at least a month of silence, of doing a little whinny with her head whenever I so much as come into her line of vision, and sometimes even pushing away the air in front of her with her palm as if to signify that I am no longer welcome to share the earth’s atmosphere with her.

But one day, deep within my ten-day escape, all alone with my science fiction and my forbidden Doritos, my ass sore from sitting on the scruffy couch for so long, my eyes television red, my mind television numb, my fifty-three-dollar capitalization reduced to a pocketful of quarters, I think to myself: This is not so bad.

It’s actually kind of good.

It’s actually kind of perfect.

Maybe this is who I really am.

Not a loner, exactly.

But someone who can be alone.

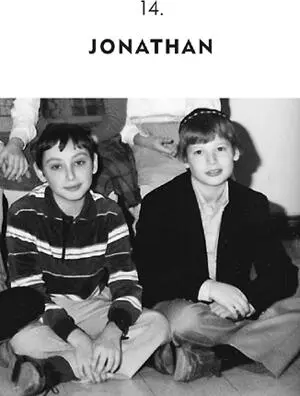

Prisoners of Zion: Gary and Jonathan face another day of Hebrew school.

BACK AT SSSQ, the bodies have been piling up for years. Auschwitz, Birkenau, Treblinka. We have special presentations in the gym, a protective fortress of prayer books around us, the American flag on one side of the stage, the Israeli flag on the other, and between them the slaughter of our innocents. As I watch the ovens open and the skeletons crumble, I become angry at the Germans and also at the Arabs, who are the same thing as the Nazis, Jew-killers, fucking murderers, they took our land or something, I hate them.

Then the other images that disturb us: Kids, white kids like us , are putting marijuana needles into their arms. They are smoking the heroin cigarettes. First Lady Nancy Reagan, standing next to the actor Clint Eastwood, a somber black background behind them, tells us, “The thrill can kill. Drug dealers need to know that we want them out of our schools, neighborhoods and our lives. Say no to drugs. And say yes to life.”

The children of the Solomon Schechter School of Queens are scared of Nazis and we are scared of drugs. If the Jewish Week had published an article revealing that Goebbels had been dealing dope to Hitler up at the Eagle’s Nest the world would finally click into place. But for now, the sad fact is that some of us will not go on to Jewish educations. We will go to public high schools where there will be gentiles, and gentiles love to “do” drugs. And how will we be able to resist the peer pressure when those thrilling drugs come our way? Clint Eastwood, sneering: “What would I do if someone offered me these drugs ? I’d tell them to take a hike.”

I picture myself walking past the lockers of Cardozo High School in Bayside, Queens, the mild-mannered public school I’m zoned for. A kid walks up to me. He seems all-American, but there’s something not quite right in his eyes. “Hey, Gnu,” he says, “you want these drugs ?”

And then I punch him in his face and scream, “Take a hike! Take a hike, you Nazi PLO scum!” And there’s a Jewish girl they’re trying to stick with their needles, and I run over to her, fists swinging, and scream, “Take a hike! Take a hike from her!” And she falls into my arms and I kiss her needle marks, and I say, “It’s going to be okay, Rivka. I love you. Maybe they didn’t give you the AIDS.”

The other holocaust we’re scared of is the nuclear one. The 1983 ABC-TV movie The Day After showed us what could happen to the good people of Kansas City, MO, and Lawrence, KS, if the Soviets were to vaporize them with thermonuclear devices. Then there is the BBC version, Threads , shown on PBS, which is widely acknowledged to be more realistic: babies and milk bottles are instantly turned to cinders, cats asphyxiate, survivors are left to eat raw radioactive sheep. (“Is it safe to eat?” “It’s got a thick coat, that should have protected it.”) I memorize the final moments before the bomb hits Yorkshire, an exchange between two ill-prepared bureaucrats, and I chant it to myself in the middle of the sclerotic hum that is Talmud class:

“Attack warning red!”

“Attack warning? Is it for real?”

Читать дальше