Akawe Asema

The rock paintings are alive. This is more important than anything else that I can say about them. As if to prove this point, we see as we approach Painted Rock Island that a boat has paused. It is a silver fishing boat with a medium horsepower outboard motor. A man leans over and scoops a handful of tobacco from a pouch, places it before the painting, and then maneuvers his boat out and goes on. Akawe asema. First offer tobacco. This makes Tobasonakwut extremely happy, as do all the offerings that we will see as we visit the other paintings. It is evidence to him that the spiritual life of his people is in the process of recovery. He swerves the boat out and chases down the man who made the offering, and then, seeing who he is, waves and cuts away. He is doubly pleased because he knows where this man sets his nets, and knows that he went ten or twelve miles out of his way to visit the rock painting. It is sunset now and will be dark before the man returns to his dock.

The Wild Rice Spirit

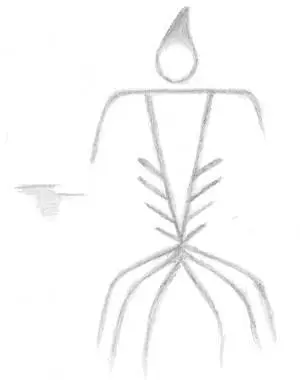

The long rays of the deepening sun reach through the channel. As we draw our boat up to the rock painting, the light warms the face of what was once a cliff. I am standing before the rock wall of Painted Rock Island and trying to read it like a book. I don’t know the language, though. The painting spreads across a ten- or twelve-foot rectangle of smooth rock, and includes several spirit figures as well as diagrams of teachings. The deep light pulls the figures from the rock. They seem to glow from the inside, a vibrant golden red. For a long while, I am only interested in the visual experience of standing at eye level with the central figures in the rock. They are simple and extremely powerful. One is a horned human figure and the other a stylized spirit figure who Tobasonakwut calls, lovingly, the Manoominikeshii , or the wild rice spirit.

Once you know what it is, the wild rice spirit looks exactly like itself. A spiritualized wild rice plant. Beautifully drawn, economically imagined. I have no doubt that this figure appeared to the painter in a dream, for I have had such dreams, and I have heard such dreams described. The spirits of things have a certain look to them, a family resemblance. This particular spirit of the wild rice crop is invoked and fussed over, worried over, just as the plants are checked throughout the summer for signs of ripening.

This year, on Lake of the Woods, the rice looks dismal. Because the high waters have invaded a whole new level of recently established rice beds, the rice is leggy and will flop over before it can be harvested. Earlier in the day, we stopped to examine Tobasonakwut’s family rice beds. At this time of the year, mid-July, the rice is especially beautiful. It is in the floating leaf stage and makes a pattern on the water like bright green floating hair. Kiimaagoogan , it is called. But upon pulling up a stalk Tobasonakwut says sadly, “There’s nothing in this loonshit,” meaning he cannot find the seed in the roots. All the energy of the plant has gone into growing itself high enough to survive the depth of the water. There will not be enough reserve strength left in the plant to produce a harvest. “And then,” Tobasonakwut goes on, “if your parents had no children, you can’t have children.” In other words, the rice crop will be affected for years.

So perhaps this year it is especially important to ask for some help from the Manoominikeshii.

When the pictures were painted, the lake was a full nine feet lower, and as it is nearly four feet higher this year than usual, some paintings of course are submerged. The water level is a political as well as natural process — it is in most large lakes now. From the beginning, that the provincial government allowed the lake levels to rise infuriated the Anishinaabeg, as the water ruined thousands of acres of wild rice beds. As it is, I mentally add about one story of rock to the painting, which at present lies only a few feet out of the water.

This is a feminine-looking drawing. The language of the wild rice harvest is intensely erotic and often comically sexualized. If the stalk is floppy, it is a poor erection. Too wet, it is a penis soaking in its favorite place. Half hard, full, hairy, the metaphors go on and on. Everything is sexual, the way of the world is to be sexual, and it is good (although often ridiculous). The great teacher of the Anishinaabeg, whose intellectual prints are also on this rock, was a being called Nanabozho, or Winabojo. He was wise, he was clever, he was a sexual idiot, a glutton, full of miscalculations and bravado. He gave medicines to the Ojibwe, one of the primary being laughter.

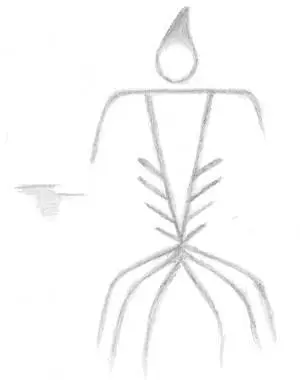

The Horned Man

This is the figure that glows brightest from the rock. He is not a devil, and he isn’t throwing away a Christian cross — the local white Christian interpretation of the painting, which has led to its close call at defacement. (At the figure’s far right, in white paint, I can still make out Jesus Christ in fairly neat lettering. But the thirty-year-old graffiti has nearly flaked off, while the original painted figures still blaze true.) As I stand before the painting, I come to believe that the horned figure is a self-portrait of the artist.

Books. Why? So we can talk to you even though we are dead. Here we are, the writer and I, regarding each other.

Horns connote intellectual and spiritual activity — important to us both and used on many of the rock paintings all across the Canadian Shield. The cross that the figure is holding over the rectangular water drum probably signifies the degree that the painter had reached in the hierarchy of knowledge that composes the formal structure of the Ojibwe religion, the Midewiwin. The cross is the sign of the fourth degree, and as well, there are four Mide squares stacked at the figure’s left-hand side, again revealing the position of the painter in the Mide lodge.

I quickly grow fond of this squat, rosy, hieratic figure. His stance is both proud and somewhat comical, the bent legs strong and stocky. His arms are raised but he doesn’t seem to be praying as much as dancing, ready to spring into the air, off the rock. When this rock was painted on a cliff, the water below was not a channel but a small lake that probably flooded periodically, allowing fish to exit and enter. Perhaps it was a camping or a teaching place, or possibly even a productive wild rice bed. Very likely it was a place where the Mide lodge was built, like Niiyaawaangashing. The painter may have been a Mide teacher, eager to leave instructions and to tell people about the activities that took place here.

Most of the major forms of communication with the spirit world are visible in this painting — the Mide lodge, the sweat lodge or madoodiswan , the shake tent. The horned figure beats a water drum. Such drums are extremely resonant, and their tone changes beautifully according to the level of the water and the player’s skill at shifting the water in the drum while beating it. (Anyone curious about the sound of the water drum can buy a CD and listen to the winners of a recent Native American Grammy, the singers Verdell Primeaux and Johnny Mike, Bless The People .) The water drum is a healing drum. In the pictograph a bear floats over the drum, and a line between the horned figure and the bear connects them with the sky world.

The line is a sign of power and communication. It is sound, speech, song. The lines drawn between things in Ojibwe pictographs are extremely important, for they express relationships, usually between a human and a supernatural being. Wavy lines are most impressive, for they signify direct visionary information, talk from spirit to spirit. In the work of some contemporary Ojibwe artists, Joe Geshick, Blake Debassige, and of course Norval Morrisseau, the line is still used to signify spiritual interaction. Contemporary native art is not just influenced by the conventions invented by the rock painters, it is a continuation, evidence of the vitality of Ojibwe art.

Читать дальше