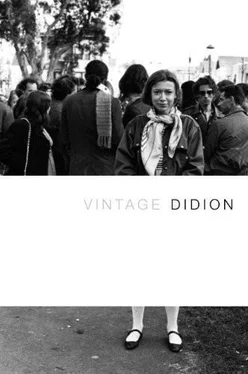

Joan Didion - Vintage Didion

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Joan Didion - Vintage Didion» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2004, Издательство: Vintage Books, Жанр: Биографии и Мемуары, Публицистика, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Vintage Didion

- Автор:

- Издательство:Vintage Books

- Жанр:

- Год:2004

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:4 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Vintage Didion: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Vintage Didion»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Vintage Didion — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Vintage Didion», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

I recall, early on, after John Ashcroft and Condoleezza Rice warned the networks not to air the bin Laden tapes because he could be “passing information,” heated debate about the First Amendment implications of this warning — as if there were even any possible point to the warning, as if we had all forgotten that our enemies as well as we lived in a world where information gets passed in more efficient ways. A year later, we were still looking for omens, portents, the supernatural manifestations of good or evil. Pathetic fallacy was everywhere. The presence of rain at a memorial for fallen firefighters was gravely reported as evidence that “even the sky cried.” The presence of wind during a memorial at the site was interpreted as another such sign, the spirit of the dead rising up from the dust.

This was a year when Rear Admiral John Stufflebeem, deputy director of operations for the Joint Chiefs of Staff, would say at a Pentagon briefing that he had been “a bit surprised” by the disinclination of the Taliban to accept the “inevitability” of their own defeat. It seemed that Admiral Stufflebeem, along with many other people in Washington, had expected the Taliban to just give up. “The more that I look into it,” he said at this briefing, “and study it from the Taliban perspective, they don’t see the world the same way we do.” It was a year when the publisher of The Sacramento Bee , speaking at the midyear commencement of California State University, Sacramento, would be forced off the stage of the Arco Arena for suggesting that because of the “validity” and “need” for increased security we would be called upon to examine to what degree we might be “willing to compromise our civil liberties in the name of security.” Here was the local verdict on this aborted speech, as expressed in one of many outraged letters to the editor of the Bee:

It was totally and completely inappropriate for her to use this opportunity to speak about civil liberties, military tribunals, terrorist attacks, etc. She should have prepared a speech about the accomplishments that so many of us had just completed, and the future opportunities that await us.

In case you think that’s a Sacramento story, it’s not.

Because this was also a year when one of the student speakers at the 2002 Harvard commencement, Zayed Yasin, a twenty-two-year-old Muslim raised in a Boston suburb by his Bangladeshi father and Irish-American mother, would be caught in a swarm of protests provoked by the announced title of his talk, which was “My American Jihad.” In fact the speech itself, which he had not yet delivered, fell safely within the commencement-address convention: its intention, Mr. Yasin told The New York Times , was to reclaim the original meaning of “jihad” as struggle on behalf of a principle, and to use it to rally his classmates in the fight against social injustice. Such use of “jihad” was not in this country previously uncharted territory: the Democratic pollster Daniel Yankelovich had only a few months before attempted to define the core values that animated what he called “the American jihad”—separation of church and state, the value placed on diversity, and equality of opportunity. In view of the protests, however, Mr. Yasin was encouraged by Harvard faculty members to change his title. He did change it. He called his talk “Of Faith and Citizenship.” This mollified some, but not all. “I don’t think it belonged here today,” one Harvard parent told The Washington Post . “Why bring it up when today should be a day of joy?”

This would in fact be a year when it was to become increasingly harder to know who was infantilizing whom.

2

California Monthly , the alumni magazine for the University of California at Berkeley, published in its November 2002 issue an interview with a member of the university’s political science faculty, Steven Weber, who is the director of the MacArthur Program on Multilateral Governance at Berkeley’s Institute of International Studies and a consultant on risk analysis to both the State Department and such private-sector firms as Shell Oil. It so happened that Mr. Weber was in New York on September 11, 2001, and for the week that followed. “I spent a lot of time talking to people, watching what they were doing, and listening to what they were saying to each other,” he told the interviewer:

The first thing you noticed was in the bookstores. On September 12, the shelves were emptied of books on Islam, on American foreign policy, on Iraq, on Afghanistan. There was a substantive discussion about what it is about the nature of the American presence in the world that created a situation in which movements like al-Qaeda can thrive and prosper. I thought that was a very promising sign.

But that discussion got short-circuited. Sometime in late October, early November 2001, the tone of that discussion switched, and it became: What’s wrong with the Islamic world that it failed to produce democracy, science, education, its own enlightenment, and created societies that breed terror?

The interviewer asked him what he thought had changed the discussion. “I don’t know,” he said, “but I will say that it’s a long-term failure of the political leadership, the intelligentsia, and the media in this country that we didn’t take the discussion that was forming in late September and try to move it forward in a constructive way.”

I was struck by this, since it is so coincided with my own impression. Most of us saw that discussion short-circuited, and most of us have some sense of how and why it became a discussion with nowhere to go. One reason, among others, runs back sixty years, through every administration since Franklin Roosevelt’s. Roosevelt was the first American president who tried to grapple with the problems inherent in securing Palestine as a Jewish state.

It was also Roosevelt who laid the groundwork for our relationship with the Saudis. There was an inherent contradiction here, and it was Roosevelt, perhaps the most adroit political animal ever made, who instinctively devised the approach adopted by the administrations that followed his: Stall. Keep the options open. Make certain promises in public, and conflicting ones in private. This was always a high-risk business, and for a while the rewards seemed commensurate: we got the oil for helping the Saudis, we got the moral credit for helping the Israelis, and, for helping both, we enjoyed the continuing business that accrued to an American defense industry significantly based on arming all sides.

Consider the range of possibilities for contradiction.

Sixty years of making promises we had no way of keeping without breaking the promises we’d already made.

Sixty years of long-term conflicting commitments, made in secret and in many cases for short-term political reasons.

Sixty years that tend to demystify the question of why we have become unable to discuss our relationship with the current government of Israel.

Whether the actions taken by that government constitute self-defense or a particularly inclusive form of self-immolation remains an open question. The question of course has a history, a background involving many complicit state and nonstate actors and going back most recently to, but by no means beginning with, the breakup of the Ottoman Empire. This open question, and its history, are discussed rationally and with considerable intellectual subtlety in Jerusalem and Tel Aviv, as anyone who reads Amos Elon or Avishai Margalit in The New York Review or even occasionally sees Ha’aretz on-line is well aware. Where the question is not discussed rationally — where in fact the question is rarely discussed at all, since so few of us are willing to see our evenings turn toxic — is in New York and Washington and in those academic venues where the attitudes and apprehensions of New York and Washington have taken hold. The president of Harvard recently warned that criticisms of the current government of Israel could be construed as “anti-Semitic in their effect if not their intent.”

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Vintage Didion»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Vintage Didion» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Vintage Didion» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.