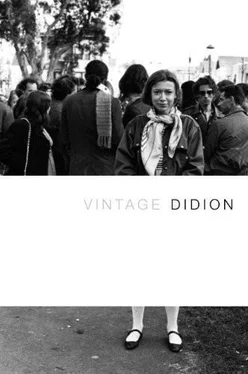

Joan Didion - Vintage Didion

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Joan Didion - Vintage Didion» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2004, Издательство: Vintage Books, Жанр: Биографии и Мемуары, Публицистика, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Vintage Didion

- Автор:

- Издательство:Vintage Books

- Жанр:

- Год:2004

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:4 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Vintage Didion: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Vintage Didion»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Vintage Didion — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Vintage Didion», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

“Average folks,” however, do not call their elected representatives, nor do they attend the events where the funds get raised and the questions asked. The citizens who do are the citizens with access, the citizens with an investment, the citizens who have a special interest. When Representative Tom Coburn (R-Okla.) reported to The Washington Post that during three days in September 1998 he received five hundred phone calls and 850 e-mails on the question of impeachment, he would appear to have been reporting, for the most part, less on “average folks” than on constituents who already knew, or had been provided, his telephone number or e-mail address; reporting, in other words, on an organized blitz campaign. When Gary Bauer of the Family Research Council seized the moment by test-running a drive for the presidency with a series of Iowa television spots demanding Mr. Clinton’s resignation, he would appear to have been interested less in reaching out to “average folks” than in galvanizing certain caucus voters, the very caucus voters who might be expected to have already called or e-mailed Washington on the question of impeachment.

When these people on the political talk shows spoke about the inability of Americans to stomach “the details,” then, they were speaking, in code, about a certain kind of American, a minority of the population but the minority to whom recent campaigns have been increasingly pitched. They were talking politics. They were talking about the “values” voter, the “pro-family” voter, and so complete by now was their isolation from the country in which they lived that they seemed willing to reserve its franchise for, in other words give it over to, that key core vote.

3

The cost of producing a television show on which Wolf Blitzer or John Gibson referees an argument between an unpaid “former federal prosecutor” and an unpaid “legal scholar” is significantly lower than that of producing conventional programming. This is, as they say, the “end of the day,” or the bottom-line fact. The explosion of “news comment” programming occasioned by this fact requires, if viewers are to be kept from tuning out, nonstop breaking stories on which the stakes can be raised hourly. The Gulf War made CNN, but it was the trial of O. J. Simpson that taught the entire broadcast industry how to perfect the pushing of the stakes. The crisis that led to the Clinton impeachment began as and remained a situation in which a handful of people, each of whom believed that he or she had something to gain (a book contract, a scoop, a sinecure as a network “analyst,” contested ground in the culture wars, or, in the case of Starr, the justification of his failure to get either of the Clintons on Whitewater), managed to harness this phenomenon and ride it. This was not an unpredictable occurrence, nor was it unpredictable that the rather impoverished but generally unremarkable transgressions in question would come in this instance to be inflated by the rhetoric of moral rearmament.

“You cannot defile the temple of justice,” Kenneth Starr told reporters during his many front-lawn and driveway appearances. “There’s no room for white lies. There’s no room for shading. There’s only room for truth…. Our job is to determine whether crimes were committed.” This was the authentic if lonely voice of the last American wilderness, the voice of the son of a Texas preacher in a fundamentalist denomination (the Churches of Christ) so focused on the punitive that it forbade even the use of instrumental music in church. This was the voice of a man who himself knew a good deal about risk-taking, an Ahab who had been mortified by his great Whitewater whale and so in his pursuit of what Melville called “the highest truth” would submit to the House, despite repeated warnings from his own supporters (most visibly on the editorial page of The Wall Street Journal) not to do so, a report in which his attempt to take down the government was based in its entirety on ten occasions of backseat intimacy as detailed by an eager but unstable participant who appeared to have memorialized the events on her hard drive.

This was a curious document. It was reported by The New York Times , on the day after its initial and partial release, to have been written in part by Stephen Bates, identified as a “part-time employee of the independent counsel’s office and the part-time literary editor of the Wilson Quarterly,” an apparent polymath who after his 1987 graduation from Harvard Law School “wrote for publications as diverse as The Nation, The Weekly Standard, Playboy , and The New Republic .” According to the Times , Mr. Bates and Mr. Starr had together written a proposal for a book about a high school student in Omaha barred by her school from forming a Bible study group. The proposed book, which did not find a publisher, was to be titled Bridget’s Story . This is interesting, since the “narrative” section of the Referral , including as it does a wealth of nonrelevant or “story” details (for example, the threatening letter from Miss Lewinsky to the president that the president said he had not read, although “Ms. Lewinsky suspected that he had actually read the whole thing”), seems very much framed as “Monica’s Story.” We repeatedly share her “feelings,” just as we might have shared Bridget’s: “I left that day sort of emotionally stunned,” Miss Lewinsky is said to have testified at one point, for “I just knew he was in love with me.”

Consider this. The day in question, July 4, 1997, was six weeks after the most recent of the president’s attempts to break off their relationship. The previous day, after weeks of barraging members of the White House staff with messages and calls detailing her frustration at being unable to reach the president, her conviction that he owed her a job, and her dramatically good intentions (“I know that in your eyes I am just a hindrance — a woman who doesn’t have a certain someone’s best interests at heart, but please trust me when I say I do”), Miss Lewinsky had dispatched a letter that “obliquely,” as the narrative has it, “threatened to disclose their relationship.” On this day, July 4, the president has at last agreed to see her. He accuses her of threatening him. She accuses him of failing to secure for her an appropriate job, which in fact she would define in a later communiqué as including “anything at George magazine.” “The most important things to me,” she would then specify, “are that I am engaged and interested in my work, I am not someone’s administrative/executive assistant, and my salary can provide me with a comfortable living in NY.”

At this point she cried. He “praised her intellect and beauty,” according to the narrative. He said, according to Miss Lewinsky, “he wished he had more time for me.” She left the Oval Office, “emotionally stunned,” convinced “he was in love with me.” The “narrative,” in other words, offers what is known among students of fiction as an unreliable first-person narrator, a classic literary device whereby the reader is made to realize that the situation, and indeed the narrator, are other than what the narrator says they are. It cannot have been the intention of the authors to present their witness as the victimizer and the president her hapless victim, and yet there it was, for all the world to read. That the authors of the Referral should have fallen into this basic craft error suggests the extent to which, by the time the Referral was submitted, the righteous voice of the grand inquisitor had isolated itself from the more wary voices of his cannier allies.

That the voice of the inquisitor was not one to which large numbers of Americans would respond had always been, for these allies, beside the point: what it offered, and what less authentic voices obligingly amplified, was a platform for the reintroduction of fundamentalism, or “values issues,” into the general discourse. “Most politicians miss the heart and soul of this concern,” Ralph Reed wrote in 1996, having previously defined “the culture, the family, a loss of values, a decline in civility, and the destruction of our children” as the chief concerns of the Christian Coalition, which in 1996 claimed to have between a quarter and a third of its membership among registered Democrats. Despite two decades during which the promotion of the “values” agenda had been the common cause of both the “religious” (or Christian) and the neo-conservative right, too many politicians, Reed believed, still “debate issues like accountants.” John Podhoretz, calling on Republicans in 1996 to resist the efforts of Robert Dole and Newt Gingrich to “de-ideologize” the Republican Party, had echoed, somewhat less forthrightly, Reed’s complaint about the stress on economic issues. “They do not answer questions about the spiritual health of the nation,” he wrote. “They do not address the ominous sense we all have that Americans are, with every intake of breath, unconsciously inhaling a philosophy that stresses individual pleasure over individual responsibility; that our capacity to be our best selves is weakening.”

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Vintage Didion»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Vintage Didion» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Vintage Didion» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.