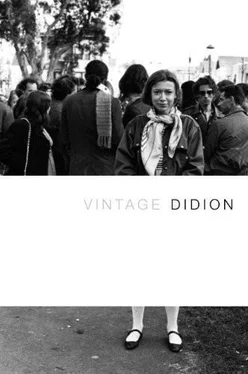

Joan Didion - Vintage Didion

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Joan Didion - Vintage Didion» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2004, Издательство: Vintage Books, Жанр: Биографии и Мемуары, Публицистика, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Vintage Didion

- Автор:

- Издательство:Vintage Books

- Жанр:

- Год:2004

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:4 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Vintage Didion: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Vintage Didion»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Vintage Didion — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Vintage Didion», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

These people recognized that even then, within days after the planes hit, there was a good deal of opportunistic ground being seized under cover of the clearly urgent need for increased security. These people recognized even then, with flames still visible in lower Manhattan, that the words “bipartisanship” and “national unity” had come to mean acquiescence to the administration’s preexisting agenda — for example the imperative for further tax cuts, the necessity for Arctic drilling, the systematic elimination of regulatory and union protections, even the funding for the missile shield — as if we had somehow missed noticing the recent demonstration of how limited, given a few box cutters and the willingness to die, superior technology can be.

These people understood that when Judy Woodruff, on the evening the president first addressed the nation, started talking on CNN about what “a couple of Democratic consultants” had told her about how the president would be needing to position himself, Washington was still doing business as usual. They understood that when the political analyst William Schneider spoke the same night about how the president had “found his vision thing,” about how “this won’t be the Bush economy anymore, it’ll be the Osama bin Laden economy,” Washington was still talking about the protection and perpetuation of its own interests.

These people got it.

They didn’t like it.

They stood up in public and they talked about it.

Only when I got back to New York did I find that people, if they got it, had stopped talking about it. I came in from Kennedy to find American flags flying all over the Upper East Side, at least as far north as 96th Street, flags that had not been there in the first week after the fact. I say “at least as far north as 96th Street” because a few days later, driving down from Washington Heights past the big projects that would provide at least some of the manpower for the “war on terror” that the president had declared — as if terror were a state and not a technique — I saw very few flags: at most, between 168th Street and 96th Street, perhaps a half-dozen. There were that many flags on my building alone. Three at each of the two entrances. I did not interpret this as an absence of feeling for the country above 96th Street. I interpreted it as an absence of trust in the efficacy of rhetorical gestures.

There was much about this return to New York that I had not expected. I had expected to find the annihilating economy of the event — the way in which it had concentrated the complicated arrangements and misarrangements of the last century into a single irreducible image — being explored, made legible. On the contrary, I found that what had happened was being processed, obscured, systematically leached of history and so of meaning, finally rendered less readable than it had seemed on the morning it happened. As if overnight, the irreconcilable event had been made manageable, reduced to the sentimental, to protective talismans, totems, garlands of garlic, repeated pieties that would come to seem in some ways as destructive as the event itself. We now had “the loved ones,” we had “the families,” we had “the heroes.”

In fact it was in the reflexive repetition of the word “hero” that we began to hear what would become in the year that followed an entrenched preference for ignoring the meaning of the event in favor of an impenetrably flattening celebration of its victims, and a troublingly belligerent idealization of historical ignorance. “Taste” and “sensitivity,” it was repeatedly suggested, demanded that we not examine what happened. Images of the intact towers were already being removed from advertising, as if we might conveniently forget they had been there. The Roundabout Theatre had canceled a revival of Stephen Sondheim’s Assassins , on the grounds that it was “not an appropriate time” to ask audiences “to think critically about various aspects of the American experience.” The McCarter Theatre at Princeton had canceled a production of Richard Nelson’s The Vienna Notes , which involves a terrorist act, saying that “it would be insensitive of us to present the play at this moment in our history.”

I found in New York that “the death of irony” had already been declared, repeatedly, and curiously, since irony had been declared dead at the precise moment — given that the gravity of September 11 derived specifically from its designed implosion of historical ironies — when we might have seemed most in need of it. “One good thing could come from this horror: it could spell the end of the age of irony,” Roger Rosenblatt wrote within days of the event in Time , a thought, or not a thought, destined to be frequently echoed but never explicated. Similarly, I found that “the death of postmodernism” had also been declared. (“It seemed bizarre that events so serious would be linked causally with a rarified form of academic talk,” Stanley Fish wrote after receiving a call from a reporter asking if September 11 meant the end of postmodernist relativism. “But in the days that followed, a growing number of commentators played serious variations on the same theme: that the ideas foisted upon us by postmodern intellectuals have weakened the country’s resolve.”) “Postmodernism” was henceforth to be replaced by “moral clarity,” and those who persisted in the decadent insistence that the one did not necessarily cancel out the other would be subjected to what William J. Bennett would call — in Why We Fight: Moral Clarity and the War on Terrorism —“a vast relearning,” “the reinstatement of a thorough and honest study of our history, undistorted by the lens of political correctness and pseudosophisticated relativism.”

I found in New York, in other words, that the entire event had been seized — even as the less nimble among us were still trying to assimilate it — to stake new ground in old domestic wars. There was the frequent deployment of the phrase “the Blame America Firsters,” or “the Blame America First crowd,” the wearying enthusiasm for excoriating anyone who suggested that it could be useful to bring at least a minimal degree of historical reference to bear on the event. There was the adroit introduction of convenient straw men. There was Christopher Hitchens, engaging in a dialogue with Noam Chomsky, giving himself the opportunity to generalize whatever got said into “the liberal-left tendency to ‘rationalize’ the aggression of September 11.” There was Donald Kagan at Yale, dismissing his colleague Paul Kennedy as “a classic case of blaming the victim,” because the latter had asked his students to try to imagine what resentments they might harbor if America were small and the world dominated by a unified Arab-Muslim state. There was Andrew Sullivan, warning on his Web site that while the American heartland was ready for war, the “decadent left in its enclaves on the coasts” could well mount “what amounts to a fifth column.”

There was the open season on Susan Sontag — on a single page of a single issue of The Weekly Standard that October she was accused of “unusual stupidity,” of “moral vacuity,” and of “sheer tastelessness”—all for three paragraphs in which she said, in closing, that “a few shreds of historical awareness might help us understand what has just happened, and what may continue to happen”; in other words that events have histories, political life has consequences, and the people who led this country and the people who wrote and spoke about the way this country was led were guilty of trying to infantilize its citizens if they continued to pretend otherwise.

Inquiry into the nature of the enemy we faced, in other words, was to be interpreted as sympathy for that enemy. The final allowable word on those who attacked us was to be that they were “evildoers,” or “wrongdoers,” peculiar constructions that served to suggest that those who used them were transmitting messages from some ultimate authority. This was a year in which it would come to seem as if we had been plunged at one fell stroke into a premodern world. The possibilities of the Enlightenment vanished. We had suddenly been asked to accept — and were in fact accepting — a kind of reasoning so extremely fragile that it might have been based on the promised return of the cargo gods.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Vintage Didion»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Vintage Didion» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Vintage Didion» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.