Despite the terrors of the past twenty-four hours — or perhaps because of them — Hepton threw back his head and laughed. The cab driver glanced into his rear-view mirror.

‘Glad somebody’s happy,’ he said. ‘Journalist, are you?’

‘What makes you say that?’

‘We get a lot of journalists come into town at twelve o’clock for a drink, then have to get a taxi back half an hour later so they can start work again. Mad, those journalists are. You know the ones I mean, down at that new place in the Isle, where the Herald ’s printed.’

‘Oh yes, the Herald,’ said Hepton casually. ‘That’s where I’m headed to, as it happens.’

‘Thought you were,’ the driver called, chuckling. ‘I’ve got a nose for that sort of thing, you see. A real nose. But first off, let’s see about getting you that clobber, eh?’

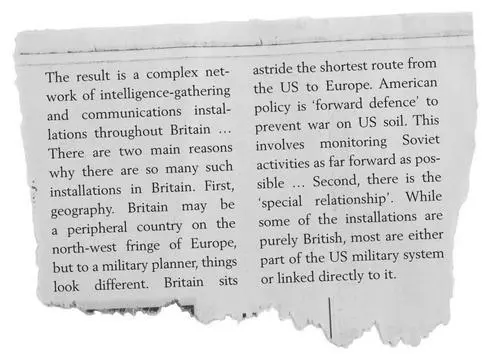

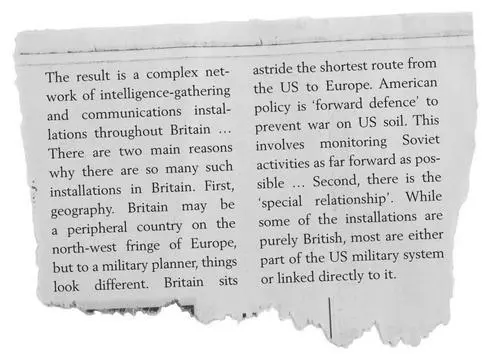

Ian Mather, Observer Magazine , 19 April 1987

The Isle of Dogs was everything Hepton had been expecting. It was, in fact, a building site, a hotchpotch of half-completed monoliths and half-demolished houses. The headquarters of the Herald , however, if not what he had hoped to find (he had fond memories of The Front Page and Citizen Kane ) was certainly what he had thought he might find. The metal and glass cube that was home to the newspaper was protected by a high security fence. A barrier lay across the road at the entrance to the site, and two security men watched from their little prefabricated building there, while video cameras scanned the perimeter.

‘Checkpoint Charlie, they call it,’ said Hepton’s taxi driver, accepting the fifteen pounds’ fare and a small tip. ‘Cheers then.’ And with that he wheeled the taxi around and away.

Hepton stared again at the construction before him, trying to find some hint of a soul. There was none. He walked towards the barrier. One of the security guards donned a cap and came to meet him.

‘Can I help you, sir?’

‘I’m here to see one of the journalists, a Miss Jilly Watson.’

‘Watson, did you say?’ The guard was already turning back towards his office. ‘Follow me, sir. Expecting you, is she?’

‘No, not really. I’m a friend of hers.’

‘I see, sir.’

The other guard lazily watched several screens, each one showing a corner of the compound. There was a mug of dark brown tea in front of him, proclaiming its owner to be the World’s Best Dad . Another bank of screens showed the interior of the large building behind them, where the workers moved like ants. The first guard looked through a sheaf of A4 printed paper on his desk.

‘Watson, J. Extension three-five-five,’ he said to himself. He punched several numbers into his telephone receiver, and, looking up, saw that Hepton was watching the screens. ‘Good, aren’t they?’

‘Yes,’ Hepton responded. It seemed everyone was a spy these days. And everyone had a camera trained on them.

The guard’s call had been connected. ‘Hello, it’s the gate here. Got someone to see Miss Watson.’ He listened to a voice speaking at the other end, then put his hand over the mouthpiece. ‘What’s the name, sir?’

This was the moment Hepton had dreaded. ‘Martin Hepton,’ he said.

‘Martin Hepton,’ the guard repeated into the mouthpiece. There was a pause while he listened again, then he motioned with the telephone towards Hepton. ‘Wants a word, Mr Hepton,’ he said.

Hepton took the receiver cautiously. ‘Hello?’ he said.

‘Martin? Is that you?’ Jilly Watson’s voice sounded vibrant.

‘Yes,’ he said.

‘What are you doing here?’ But it wasn’t a sniping question; rather, it was filled with honest and welcome surprise. Hepton lightened: she was pleased that he had come.

‘I wanted to see you,’ he said.

‘Great! But they won’t let you in here. You need passes and all that kind of stuff. We’re not allowed visitors; a bit like a prison.’ She laughed. ‘If nobody gets in, nobody can steal our scoops, that’s what they reckon. What time is it?’ She checked her watch. ‘One thirty already! Christ, I haven’t eaten yet, have you?’

‘No.’

‘Well, that’s settled then. You can take me to lunch. There isn’t much around here, but there’s a wine bar not too far. Do you have a car?’

‘No, I came by taxi.’

‘Well, wait at the gate and I’ll bring my car round. Okay?’

‘Fine.’

‘Martin...?’

‘Yes?’

‘It’s good to hear your voice.’

Click. The connection went dead.

‘Coming down, is she, sir?’ asked the first guard. Hepton nodded. ‘Nobody’s allowed in, you see,’ the guard went on. ‘Security.’

‘Bloody daft if you ask me,’ rejoined the second guard, cupping his hands around his mug. The first guard now took off his cap and sat down.

‘Ours not to reason why,’ he said.

Hepton nodded agreement, but he wasn’t about to complete the couplet.

The guard operated the barrier from inside the gatehouse, while Hepton slid into the reassuringly familiar seat of Jilly’s red MG sports car. She leaned across to peck him on the cheek, then waved towards the gatehouse and revved the car out onto the main road.

‘You look great!’ Hepton shouted above the wind and the sound of the engine.

‘So do you,’ Jilly replied. ‘You never used to dress like that.’

Hepton examined his newly purchased clothes. ‘I’m on holiday.’

‘In London?’

‘Yes.’

‘And you thought you’d surprise me. How lovely.’ The smile left her face. ‘I did mean to get in touch, Martin. I didn’t want to lose you as a friend. But...’

‘Forget it.’ He tried to steel himself; this wasn’t the time to become emotional. ‘So how’s the job?’

‘Oh, fine.’ But her voice had taken on a false edge.

‘Really?’ he prompted.

‘Well, no... not really. In fact, it’s awful. I seem to get all the shitty jobs to do, all the really boring things. I think the editor likes the idea of me, he just doesn’t like me . If that makes any sense.’

Hepton nodded. ‘It makes sense.’ He could no longer contain his next question, his first real question. ‘Have you heard anything from Mike Dreyfuss?’

‘No, nothing, I sent some flowers to the hospital in Sacramento, but I don’t know if they arrived. Did you know they’d taken him to Sacramento? They tried to keep it a secret, but our sister paper in the States found out.’ She sighed. ‘Poor Mickey.’

‘Yes. I’m trying to get in touch with him.’

‘With Mickey? But why?’

So he told her.

They sat at a corner table in the wine bar. The waitress had cleared away their plates and brought them coffee. There was an inch of wine left in the bottom of the bottle, and Hepton poured it into Jilly’s glass. She had sat quietly and attentively all through lunch, while he had continued his story. Now and then she would ask a question, in order to clarify some point, but other than that she was silent. Hepton remembered the day she had ordered him to teach her about satellites. She had been the same then.

Occasionally she jotted a few notes into a clean page of her Filofax, and when Hepton had finished talking, she drew a thick line beneath what she had written so far, then numbered the individual points.

‘Well?’ he asked. ‘Do you think I’m going mad, or is something happening out there?’

She gave her answer some thought. ‘I don’t think you’re mad, no. But at the moment you don’t really know what’s going on, you don’t have any proof that anything’s going on, and you’ll have a hard job convincing anyone that anything’s going on. Despite which, I believe you. But then I’m a reporter, we’ll believe anything.’ She saw that Hepton was looking dispirited and squeezed his hand. ‘You’re safe now, Martin. You’ve got me to look after you.’ He smiled at this, but knew she could see he was tired; more than that, he was drained. He needed rest and sleep and to forget about the past few days for a little while.

Читать дальше