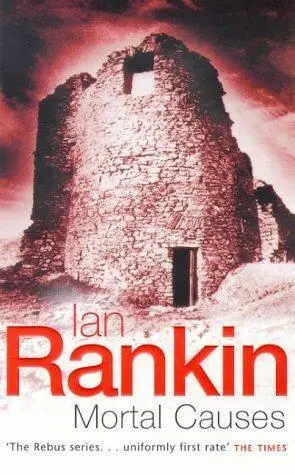

The sixth book in the Inspector Rebus series, 1994

A lot of people helped me with this book. I'd like to thank the people of Northern Ireland for their generosity and their `crack'. Particular thanks need to go to a few people who can't be named or wouldn't thank me for naming them. You know who you are.

Thanks also to: Colin and Liz Stevenson, for trying, Gerald Hammond, for his gun expertise; the Officers of the City of Edinburgh Police and Lothian and Borders Police, who never seem to mind me telling stories about them; David and Pauline, for help at the Festival.

The best book on the subject of Protestant paramilitaries is Professor Steve Bruce's The Red Hand (OUP, 1992). One quote from the book: `There is no "Northern Ireland problem" for which there is a solution. There is only a conflict in which there must be winners and losers.’

The action of Mortal Causes takes place in a fictiionallsed summer, 1993, before the Shankill Road bombing and its bloody aftermath.

Perhaps Edinburgh's terrible inability to speak out, Edinburgh's silence with regard to all it should be saying, Is but the hush that precedes the thunder, The liberating detonation so oppressively imminent now? Hugh MacDiarmid

We're all gonna be just dirt in the ground.

He could scream all he liked.

They were underground, a place he didn't know, a cool ancient place but lit by electricity. And he was being punished. The blood dripped off him onto the earth floor. He could hear sounds like distant voices, something beyond the breathing of the men who stood around him. Ghosts, he thought. Shrieks and laughter, the sounds of a good night out. He must be mistaken: he was having a very bad night in.

His bare toes just touched the ground. His shoes had came off as they'd scraped him down the flights of steps. His socks had followed sometime after. He was in agony, but agony could be cured. Agony wasn't eternal. He wondered if he would walk again. He remembered the barrel of the gun touching the back of his knee, sending waves of energy up and down his leg.

His eyes were closed. If he opened them he knew he would see flecks of his own blood against the whitewashed wall, the wall which seemed to arch towards him. His toes were still moving against the ground, dabbling in warm blood. Wherever he tried to steak, he could feel his face cracking: dried salt tears and sweat.

It was strange, the shape your life could take. You might be loved as a child but still go bad. You might have monsters for parents but grow up pure. His life had been neither one nor the other. Or rather, it had been both, for he'd been cherished and abandoned in equal measure. He was six, and shaking hands with a large man. There should have been more affection between them, but somehow there wasn't. He was ten, and his mother was looking tired, bowed down, as she leaned over the sink washing dishes. Not knowing he was in the doorway, she paused to rest her hands on the rim of the sink. He was thirteen, and being initiated into his first gang. They took a pack of cards and skinned his knuckles with the edge of the pack. They took it in turns, all eleven of them. It hurt until he belonged.

Now there was a shuffling sound. And the gun barrel was touching the back of his neck, sending out more waves. How could something be so cold? He took a deep breath, feeling the effort in his shoulder-blades. There couldn't be more pain than he already felt. Heavy breathing close to his ear, and then the words again.

`Nemo me impune lacessit.’

He opened his eyes to the ghosts. They were in a smoke filled tavern, seated around a long rectangular table, their goblets of wine and ale held high. A young woman was slouching from the lap of a one-legged man. The goblets had stems but no bases: you couldn't put them back on the table until they'd been emptied. A toast was being raised. Those in fine dress rubbed shoulders with beggars. There were no divisions, not in the tavern's gloom. Then they looked towards him, and he tried to smile.

He felt but did not hear the final explosion.

Probably the worst Saturday night of the year: which was why Inspector John Rebus had landed the shift. God was in his heaven, just making sure. There had been a derby match in the afternoon, Hibs versus Hearts at Easter Road. Fans making their way back to the west end and beyond had stopped in the city centre to drink to excess and take in some of the sights and sounds of the Festival.

The Edinburgh Festival was the bane of Rebus's life. He'd spent years confronting it, trying to avoid it, cursing it, being caught up in it. There were those who said that it was somehow atypical of Edinburgh, a city which for most of the year seemed sleepy, moderate, bridled. But that was nonsense; Edinburgh's history was full of licence and riotous behaviour. But the Festival, especially the Festival Fringe, was different. Tourism was its lifeblood, and where there were tourists there was trouble. Pickpockets and housebreakers came to town as to a convention, while those football supporters who normally steered clear of the city centre suddenly became its passionate defenders, challenging the foreign invaders who could be found at tables outside short-lease cafes up and down the High Street.

Tonight the two might clash in a big way.

'It's hell out there,' one constable had already commented as he paused for rest in the canteen. Rebus believed him all too readily. The cells were filling nicely along with the CID in-trays. A woman had pushed her drunken husband's fingers into the kitchen mincer. Someone was applying superglue to cashpoint machines then chiselling the flap open later to get at the money. Several bags had been snatched around Princes Street. And the Can Gang were on the go again.

The Can Gang had a simple recipe. They stood at bus stops and offered a drink from their can. They were imposing figures, and the victim would take the proffered drink, not knowing that the beer or cola contained crushed up Mogadon tablets, or similar fast-acting tranquillisers. When the victim passed out, the gang would strip them of cash and valuables. You woke up with a gummy head, or in one severe case with your stomach pumped dry. And you woke up poor.

Meantime, there had been another bomb threat, this time phoned to the newspaper rather than Lowland Radio. Rebus had gone to the newspaper offices to take a statement from the journalist who'd taken the call. The place was a madhouse of Festival and Fringe critics filing their reviews. The journalist read from his notes.

`He just said, if we didn't shut the Festival down, we'd be sorry.’

'Did he sound serious?’

`Oh, yes, definitely.’

`And he had an Irish accent?’

'Sounded like it.’

`Not just a fake?’

The reporter shrugged. He was keen to file his story, so Rebus let him go. That made three calls in the past weak, each one threatening to bomb or otherwise disrupt the Festival. The police were taking the threat seriously. How could they afford not to? So far, the tourists hadn't been scared off, but venues were being urged to make security checks before and after each performance.

Back at St Leonard's, Rebus reported to his Chief Superintendent, then tried to finish another piece of paperwork. Masochist that he was, he quite liked the Saturday backshift. You saw the city in its many guises. It allowed a salutory peek into Edinburgh's grey soul. Sin and evil weren't black – he'd argued the point with a priest – but were greyly anonymous. You saw them all night long, the grey peering faces of the wrongdoers and malcontents, the wife beaters and the knife boys. Unfocused eyes, drained of all concern save for themselves. And you prayed, if you were John Rebus, prayed that as few people as possible ever had to get as close as this to the massive grey nonentity.

Читать дальше