He went on: “First, by a disastrous mischance, Webster himself got hurt, so this pair, from that time to this, have had no chance to confer, to cook up some new tale to square with the unexpected development. Second, by a still more disastrous mischance, Mrs. Val, when left on her own, turned out a very poor liar. She had no talent at all, and told tale after tale to the police, each more incredible than the last, and none, until she took the stand just now, bearing any relation to the truth. Third, by the most disastrous mischance of all, Webster turned out a slick, cool liar, adept, by his own facetious admission, at inventing things for the police, first a tale of amnesia that served him well for a time, then a tale of acrobatics that served him a little too well.”

He tossed the handkerchief again, batting it as a cat bats a mouse, and said: “In other words, in this card game, if we exclude, as we must, my distinguished colleague Mr. Brice from any part in stacking the deck, Mrs. Val found herself — and I intend no pun — in the position of dummy. She couldn’t play until Webster finessed to her hand. Then, for a time, she played very well, following his lead closely, though not seeming to, as she mixed everything with the story of her life in a moving, convincing way. But watch the way, the almost Biblical way, she made one misplay. Toward the end, Webster hurried over the one bad part of his story. Try as he would, he could not talk down that shell, with his thumbprints on it, that he fired, as I think, to compel Val to jump, or perhaps to startle him into jumping. If, in his story, Val fired it, at what, in heaven’s name? At Webster? At Mrs. Val? How could he miss at a point-blank range? So Webster invented a cat, a cat which we are asked to believe came from nowhere and, instead of running away from a ruckus, was actually strolling toward it. But at this moment the eternal Eve in Mrs. Val tempted her to take her eye off the cards and turn it on her pictures — very pretty ones, understandably a matter of pride with her.”

He let that soak in, and then: “Now, though I would like to have questioned Webster in regard to this remarkable cat, I refrained, as it occurred to me: if this card she neglected to watch was the one she couldn’t pick out when I let her choose from the pack, it would prove beyond a doubt what I suspected about Webster’s tale. I risked the state’s whole case on this one vital point. You heard me: I offered the pack, the whole pack, and nothing but the pack to pick the card. I asked her to name the animal Val had shot at, as Webster told it here, and she couldn’t. She heard no cat. She saw no cat. There w as no cat — and no scene on the ladder as Webster described that scene! ”

There was more, a great deal more, but I didn’t quite hear it, on account of a ringing in my ears. Mr. Brice made a speech, a terrific speech, smacking out all that had been said against us. The judge instructed the jury, and around half past two of maybe the fifth day of the trial, it went out.

The judge went, after calling some kind of recess, and a buzz went over the place, now that people could talk. Lucas went. Suddenly Holly got up, came over, took my hand, and spoke my name, the first word she had said to me, just between us two, since that morning when we held hands in her car. Brice grabbed her hand and pulled it away. He said: “Damn it, Mrs. Val, haven’t you done enough, wrecking this whole case while you admired your cheesecake, without this? Suppose a juror sees it? Or a bailiff? Don’t you know there’s no such grapevine as the door of a jury room?”

She pulled her hand from his and put it back in mine. She said: “I’m sorry, Mr. Brice, if I haven’t acted to suit you, but I may never see Duke again, and there are things I have to say to him — if you’ll excuse me.”

“I beg your pardon, Mrs. Valenty.”

He went back to his place, peevish, yet pulling for us both.

She said: “Duke, do you love me?”

“I said so, didn’t I?”

“As I did, darling, and do again. At least they didn’t break us, to set us against each other. Duke, one thing I have to say. It wasn’t that I doted on — cheesecake, whatever that is. But I had to show them, they had to know, what Val would have done to me, and what you did for me... Duke, it seemed wonderful, heaven on this earth, that one day you would see me as I was created to be. I little dreamed the whole world would, that I must practically undress in front of them all. We all get what we pray for. The trouble is, we get it all.”

The whispering went on, but I was stretched on my back and could only hear this crowd, not see it. She pushed pillows under my head, so at last I got a view of what went on. It was a mob, with everyone staying put, for fear they’d lose their place when the jury came in with the verdict. Lippert was gone, not having been called back to the stand, the cops were gone, the colored boy was gone. But the Valenty sisters were there, and Mr. and Mrs. Hollis, huddled with Marge and Bill. That huddle caught my eye, as Marge seemed to be frantic, and she never fussed up over nothing. And then here the four of them came, she leading the way through the gate. She whispered with Holly a minute, then stooped over me. She said: “Duke, that cat? Did it by any chance have a bell?”

“I said so, didn’t I?”

“No! You said: ‘He shot at a cat’ — like you didn’t even believe it yourself — ‘and I let go the tank with my right.’ If only, just once, you could have forgotten your left and your right and told what happened, so someone could understand it.”

I said I was sorry, and she turned away. Then Holly was there, pulling a chair up close, and I asked what it was about, and what difference it made whether I mentioned the cat bell or not. She said: “Nothing you could help, and I’ll never blame you for it. It wasn’t a bell, Duke. It was a spur, the one the colored boy heard. The same one as caught in a flag, the night Lincoln got shot.”

She said it solemn, and I could see she believed every word. By then Brice was there, over his peeve, now that he’d heard this news, and taking it very serious. Holly said to me: “Marge was the one who realized that when I didn’t hear that spur, it proved my heart was pure.”

“Mine was set to kill.”

“But for my sake only. You could hear, but you weren’t meant. Only Val was called.”

“He did some praying too.”

“When did Val ever pray?”

“For Hollis Hill. He got it.”

Her eyes opened wide, but about that time Brice put her hand in mine. He said: “Mrs. Val, I apologize — maybe, maybe you proved your case, instead of ruining it.” And then, to me: “If she’s a socker, boy, now let her sock. The door of a jury room can even hear heartbeats. From now on it’s a question of faith.”

He left us, and our hands gripped together, but hers so hard it locked on mine like a clamp. She closed her eyes, and I did, and it was pure communion in prayer.

The lights came on, the judge came in, the old geezer spoke his piece, and once more the court was in session, with the judge calling the jury back in, to see how things were going. The foreman talked pretty glum, said he saw no chance of agreement. A gray-haired woman stood up, said: “We can agree. What’s more, we will.” The judge said they must try, and recessed until nine. Marge raced through the gate, whispered: “She knows! Oh, thank God, she’s got it!”

“How do you find the defendant Holly Valenty?”

“Not guilty.”

“How do you find the defendant Duke Webster?”

“Not guilty.”

She bowed her head and I closed my eyes, each to pray our thanks up before people swarmed all around. I was raised on spurs; my father was a packer in the Sierras on the Truckee, I know what they sound like, which is more like tambourine clickers than any bell. What went by was a cat, that had probably been under the pump-house and made tracks when things got noisy. But when her hand at last was tucked into mine, so thin, so tired, so strained compared with what it had been, I knew, and will believe the rest of my life, that John Wilkes Booth was on Hollis Hill that night, and knew who he was looking for.

Читать дальше

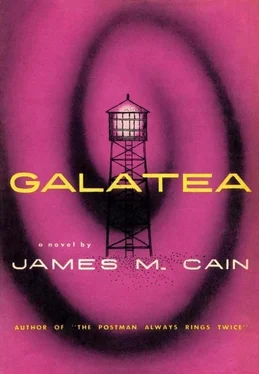

![Джеймс Кейн - Почтальон всегда звонит дважды [сборник litres]](/books/412339/dzhejms-kejn-pochtalon-vsegda-zvonit-dvazhdy-sborni-thumb.webp)