While I was talking, she had listened and not listened, staring off part of the time, as though rehearsing what she would say, and in her lap part of the time, at an envelope she had there. Lucas watched her, more than he seemed to watch me, and made some notes on a card. When he started to cross-examine, he did it very friendly, first straightening up my blankets, asking how I felt, and making a little crack about my recovery of memory. I bore in mind to be reckless, and handed it back as he gave it, as though the memory was a bit of a joke. He kept it up, being so funny I had to laugh myself, and of course I’d try to top him. Then he began to bore in, until Brice got up and objected. There seemed to be some kind of rule that if I hadn’t been asked about it on direct examination, I couldn’t be grilled for it on the cross. Brice said it was “irrelevant, a waste of time,” but Lucas said he had asked the police about it, in presenting the state’s case, and could go into it therefore, here now questioning me. And then: “As to irrelevance, it has a solemn bearing on this case that this defendant, as a means of obstructing justice, has already invented one complicated, ingenious, and incredible story, which he regards so lightly as to joke about it, and may have invented another — once he heard about Sickles.”

The judge held it was proper, and we went over and over and over it, my memory there at the hospital; and repeatedly, when I was to “tell in my own words” the way things happened, I could tell nothing at all. When at last I burst out: “Listen, Mr. Lucas, suppose you try facing a murder rap, and see what you make up” — that did it. He insisted I had made it up, every word about Arizona, and I said: “Just to protect myself — until I knew where I was.” He made me repeat it, and I realized how it sounded. Then, at last, he moved on to Sickles, and I said: “It was a big case they had — several years ago.” That got a laugh, even from the judge, and I realized it was the booby trap. Because of course, if I’d been making anything up, presumably I’d have got the thing straight. But Lucas just laughed too, and said: “Several score years ago, Webster. Sickles lost a leg at Gettysburg. You need a clerk to look up your cases.” That got an even bigger laugh, and on it, quite suddenly, he sat down, without going into the main event on the ladder at all.

It helped a little, maybe, that Brice called Daniel and pinned the gun switch on him, but not much. I had led with my chin and landed.

I had taken all day and part of the next morning, so it was the afternoon of the third day of the trial when she took the stand, white, grim, and tense. After the usual preliminaries, Brice gave her a general question: “Now please tell the jury, Mrs. Valenty, in your own words, what led up, the main events, in any way relevant, to the death of your husband.” She answered, very slow: “In my own words, Mr. Brice, let me say at the start that none of it had any relation to what I told the police officers. I said what they’ve said I said. I made things up — not to shield myself, as it never entered my mind that I would be accused. To hush up for my husband what he tried to do to me, so it never, never would come out. I remind you, Mr. Brice, that after I got down from the tank, after screaming no doubt, since a point has been made of that — both the men were alive, groaning there on the ground. And if I did what I did with the gun, I’m not ashamed, I’m proud of it. And if Duke Webster made things up, he had reason, after the way one police officer practically sold him to slavery. And if Mr. Lucas is making things up, misrepresenting Duke as he is — no doubt he has reason too, after the part he played in my husband’s designs on my life.”

Wham.

“Just a minute!”

“Yes — Mrs. Valenty — please.”

Lucas was white, Brice hardly able to talk, she icy, a tight little smile on her face, as she watched the effects of what made my poor little bombshell look like a firecracker. The judge told the jury to retire, and when they had clumped out, said: “Mr. Brice, what does this mean?”

“I’m completely caught by surprise.”

“Mrs. Valenty?”

“It means that Mr. Lucas, knowing my husband was set on a child, though the doctor had said it would kill me, didn’t even make one phone call to warn me what was in store for me. It means my husband rang him, before he was state’s attorney, to find out who made the decision in case one had to be made, as to the life that would be spared — a conversation that I overheard — and that he did not, not ever , ring me. He was my husband’s friend, but perhaps it won’t be such fun to accuse the widow of murder.”

The judge argued with her, saying it was not up to Lucas to discuss his client’s affairs, and Brice argued with her, saying it was “utter folly” to claim justifiable homicide. She said: “If you don’t want my case, Mr. Brice, I can get somebody else. But I can tell you right now, we’re going to try my case, and not some case you think ought to be my case. My husband wanted me dead, and Mr. Lucas knew it. That’s the first event that led to my husband’s decease. I was married to Death, and he pursued me to the end — but didn’t get me, thanks to a brave boy, Duke Webster. That’s my case, and I won’t have any other.”

Brice wiped the sweat from his face, but Lucas took it quite calm.

He said: “The call was made, Your Honor, exactly as she says, and I’ll stipulate it, if that helps, or take the stand, if Brice wants — though it may surprise her what I said at the other end, which she apparently didn’t hear. But I see nothing I can object to. If that’s her case, I may feel, as Brice does, she’s courting complete disaster — but there’s nothing I can object to.”

“Bring the jury in.”

She ripped along with it, on the same question all afternoon, and told of her childhood, St. Mary’s, the oxen, the church, the holly, all the stuff that had meant so little to me but that the jury seemed to get the point of. She told of her “weakness,” and the relation it had to Val’s hopes for a child. It turned out that Hollis Valenty was ten times as dark an idea as Bill had mentioned to me, and that the volcanoes I’d heard in the summer were plenty real. Toward the end of the day she opened the envelope she held in her lap, and broke out the pictures that got such a play, “taken of me, by my husband’s photographer, on my wedding day, and by myself, with a camera I have, by working it with a string — as I became, little by little, with Duke Webster’s help.”

Brice squawked as usual, and the court warned her that if introduced, the pictures would be public property, subject to use by the press, but she said: “I want the jury to see what I’m talking about. Why I could have no child, as natural birth was impossible, and an operation, a Caesarean as it’s called, was impossible too, as no stitches could hold in such fat.”

So the pictures went to the jury, and the men looked away quick, but the women, the three middle-aged women at the far end of the box, studied each separate one. The papers got them too, and ate them up, hog-wild, just why I don’t quite know. But some, the fat ones, were too ugly to be quite decent, and the others, the slim ones in bra and panties, were just a little too pretty. There was a pause during the looksee, and she sat staring at me, her face turning pink.

“Webster, is there anything on earth, anything you know I can tell her, any message you can send, that’ll stop this insane recital?”

Brice had stopped by the hospital that night on his way to see her, and after saying that, in spite of the Arizona fumble, my testimony had helped a lot, he got bitter about her and “this damned surprise she’s sprung on me.”

Читать дальше

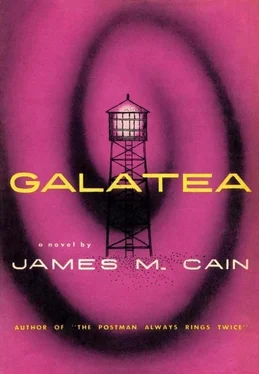

![Джеймс Кейн - Почтальон всегда звонит дважды [сборник litres]](/books/412339/dzhejms-kejn-pochtalon-vsegda-zvonit-dvazhdy-sborni-thumb.webp)