“To atone for what?”

The senator’s smile faded, disappeared. “You do keep your nose to the grindstone, don’t you?”

“If you mean,” Caldwell said sharply, “the world’s troubles, the troubles in this country, poverty, bigotry, that kind of thing—what have they to do with us? I’m not responsible for them in any way.”

“A comfortable view.”

Caldwell’s gesture took in the entire room. “I’m not even responsible for these people’s troubles. I just happen to share them.”

The senator was silent.

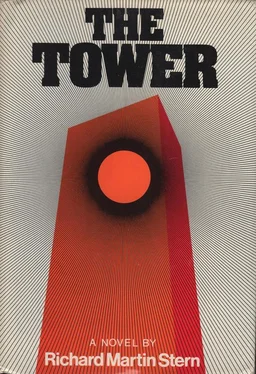

“If you’re thinking,” Caldwell said, “that because I designed this building I am responsible for its failures, I deny that. The design was, and is, sound. I don’t know all that has happened to produce this end result, but it is not my design that is to blame.”

“I think your reputation is secure,” the senator said, “and that’s the important thing, isn’t it?”

Caldwell studied the senator’s face for mockery. He found none. He relaxed a trifle.

“You asked me,” the senator said, “how to explain Grover Frazee’s behavior. I think I can in one word: panic.” He too looked around the room.

In the far comer the heavy rock beat once more blared from the transistor radio. The almost-naked girl gyrated endlessly. Her eyes were closed, her movements erotically explicit; the world was shut out.

In another comer a mixed group was joined in song. The senator listened carefully.

“‘The Battle Hymn of the Republic,’” he said, “or ‘Onward, Christian Soldiers.’ With my tin ear I can’t tell which.”

By the bar the three religious leaders who had participated in the ceremonies in the plaza conferred: the rabbi, the Catholic priest, and the Protestant minister.

“I can think of a good subject for prayer,” the senator said. “It would have to do with deliverance from a fiery furnace. Nebuchadnezzar would have dug this scene, wouldn’t you say?”

Caldwell said suddenly, “All right, I will have to admit that I share the responsibility. It is not all mine, but I share it.”

The senator stifled a smile. “It doesn’t really matter now, does it?” His voice was gentle.

“It does to me.”

“Ah,” the senator said then, “that’s a different story.”

“There is nothing fallacious in the design.”

“I’m sure of it.”

“Execution. There is where the trouble begins. When you turn the actual work over to others, you have lost control.”

“It’s a hell of a feeling, isn’t it,” the senator said, “when you have to turn over to somebody else something you’ve sweated over?”

There was a long silence. “In your own way.” Caldwell said slowly, “you are a wise man. And compassionate. You make me feel better, cleaner. Thank you.” He started to turn away.

“Which group?” the senator said. He no longer stifled his smile. “Dancing, song or prayer?”

Some of the perceptible tension went out of Caldwell’s narrow shoulders. He half-turned and his smile was easy. “I may sample them all.”

“Good for you,” the senator said.

He walked slowly toward the office, alone. “And now, physician,” he said almost whispering, “heal thyself.”

The governor was coming out of the office. His expression was inscrutable. “Come along, Jake,” he said. “We’ve got good news, I hope.” He paused. “But if this try fails too, then I think we are really going to have panic. We may anyway.” He paused again. “The traditional rush for the lifeboats or the exit.”

The governor found a chair and climbed upon it. He raised his voice. “I promised news if and when there was any. Now I want your attention.”

The singing died away. Someone turned down the transistor radio’s volume. The room was hushed.

“We are going to try again to get a line into this room,” the governor said. “This time—”

“More crap!’ Cary Wycoff’s voice dull with anger, tinged with terror. “Another sugar pill to keep us quiet!”

“This time,” the governor said, and his voice carried through Cary’s, “they are going to try to shoot the line in from a helicopter.” He paused. “I want this entire side of the room cleared so nobody will be hurt if the shot is successful.” He beckoned the fire commissioner. “Have two or three men standing by to pounce on the line when it comes through the windows. Then—”

“When?” Cary shouted. “You mean if! And you know goddam good and well that it isn’t going to happen.” The words were almost running together now. “All along you’ve kept things from us, made your own decisions, your own little deals—” He took a deep shuddering breath.

“We’re stuck here! Right from the start it’s been a fuckup! Rotten clear through, the whole city government!”

From the crowd behind Cary Wycoff there was a low, angry murmur.

“Easy, Cary,” Bob Ramsay said. He shouldered his way through the crowd to tower over Wycoff. “Easy, I say. Everything has been done that could be, and now this—”

“Shit! Give the voters that crap, don’t give it to us. We’re here to—die, man! And who’s responsible? That’s what I want to know. WHO?”

“I’m afraid we all killed Grandma.” Senator Peters’s voice raised enough for attention. He faced Wycoff and took his time. “Ever since I’ve known you, Cary, you’ve had more questions than a tenement has rats. But damned few answers, only reactions. Have you wet your pants yet? You’ve made every other infantile move.”

Cary took a deep breath. “You can’t talk to me like that.”

“Give me one reason why not.” The senator was smiling. It was not a pleasant smile. “By your standards, I’m an old man, but don’t let that bother you if it’s violence you’re thinking of. In the neighborhood I grew up in a ten-year-old kid would eat you for breakfast.”

Cary was Silent, indecisive.

“All of you,” the senator said, “simmer down. The man is trying to tell you what to do. Now, goddammit, listen!” Suddenly the governor was smiling. “I’ve said it all,” he said. He pointed. “Look!”

They all turned. A helicopter was swinging toward the bank of broken-out windows, its staccato engine sound growing louder by the moment.

Inside the chopper: a man, Kronski thought, could spend a lifetime in one of these contraptions and never get his sea legs. Boats, even small boats in heavy seas, move with some kind of rhythm. All this chopper did was buck and jump, and how in the hell the chief thought he could even hit the building, let alone the windows, he didn’t know.

His stomach was bucking and jumping too, and he swallowed hard, swallowed again, and breathed deep in the cold air.

He could see faces now inside the Tower Room. They stared at the chopper as at a vision.

The pilot looked at Kronski. There was question in his eyes.

“Closer!” Kronski roared. “Closer, goddammit!” He bloody well wanted only one shot, he told himself, and then back to solid ground, or at least the solidity of that Trade Center roof.

The pilot nodded shortly. He moved his control stick as if it were a fragile thing that might suddenly break loose in his hand.

The building moved toward them. The faces inside were plainer. The bucking and jumping increased.

“Close as I’ll go!” the pilot said. “Shoot from here!”

Inside the room people were on the move now, scurrying to one side of the room. A large man was the fire commissioner—was waving his arms to hurry them on.

Kronski raised his gun and tried to take a sight. One moment he was looking at the gleaming mast of the building, and the next moment what he saw was a row of intact windows below the Tower Room. The goddam business he had ever engaged in. He raised his voice in a great shout: “Can you, for Christ’s sake, hold this thing still?”

Читать дальше