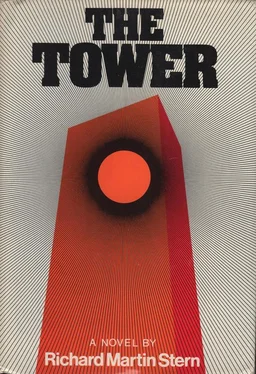

Richard Martin Stern

THE TOWER

“It is the world’s tallest structure, and the most modern, an enduring tribute to man’s ingenuity, skill, and vision. It is a triumph of imagination”

—GROVER FRAZEE at The World Tower dedication ceremonies.

“A monument to Mammon, product of man’s insatiable ego, an affront to the gods. That so much treasure should have been poured into the construction of this—this monstrosity while poverty, yes, and even hunger still stalk the land, is an abomination! There will be inevitable Divine retribution!”

—THE REVEREND JOE WILLIE THOMAS in a press interview.

“Eyewitness accounts and expert testimony are at such variance that it is difficult, if not impossible, to know where the truth concerning this disaster may be found.”

—OFFICIAL REPORT OF THE COMMITTEE OF INQUIRY.

For one hundred and twenty-five floors, from street level to Tower Room, the building rose tall and clean and shining. Above the Tower Room the radio and television spire thrust sharply against the sky.

By comparison with the twin masses of the nearby Trade Center, the building appeared slim, almost delicate, a thing of fragile-seeming grace and beauty. But eight subbasements beneath the street level its roots were anchored deep in the bedrock of the island; and its core and external skeleton, cunningly contrived, had the strength of laminated spring steel.

When fully occupied, the building would house some fifteen thousand people in its offices and studios and shops; in addition it would accommodate twenty-five thousand visitors a day.

Through its telephone, radio, and television systems operating at ground level, broadcasting through the atmosphere or via satellite, its sphere of communication was, quite simply, the earth.

It could even communicate with itself, floor to floor, subbasement to gleaming tower.

Level by level it had risen, a marvel for all to see.

The great cranes hoisted steel into position and held it while the bedlam clamor of rivet guns gave proof that it was being secured; then, their work at one level completed, the cranes, like sentient monsters, hoisted each other to new positions to repeat the process.

As the structure grew, its arteries, veins, nerves, and muscles were woven into the whole: miles of wiring, piping, utility ducting, cables and conduits; heating, ventilating, and air-conditioning ducts, intakes, and outlets—and always, always the monitoring systems and devices to oversee and control the building’s internal environment, its health, its life.

Sensors to relay information on temperature, humidity, air flow and content; computers to assimilate the data, evaluate them, issue essential instructions for continuation or change.

Are the upper ten floors, still exposed to the setting sun’s heat, warmer than optimum? Increase their flow of cool conditioned air.

Are the first ten floors above street level now cooling too rapidly in the dusk? Reduce their air-conditioning flow, and, as necessary, feed in heated air.

The building breathed, manipulated its internal systems, slept only as the human body sleeps: heart, lungs, cleansing organs functioning on automatic control, encephalic waves pulsing ceaselessly.

Dull silver was the building’s basic color—anodized aluminum curtain panels covering the structural steel; the whole pierced by tens of thousands of green-tinted tempered-glass windows.

It stood in a plaza of its own, by its height dominating the downtown area. At its base three-story arches enclosed a perimeter arcade. Great doors led into the two-story concourse, to the elevators in the core structure, the stairs and escalators and shops in the lobbies themselves.

Men had envisioned it, conceived it, and constructed it, sometimes almost lovingly, sometimes with near hatred, because, like all great projects, the building had early on developed a character of its own, and no man intimately associated with it could escape involvement.

There is, it seems, a feedback. What man creates with his hands or his mind becomes a part of himself. And there, on this morning, the building stood, its uppermost tip catching the first rays of sunrise while the rest of the city still slept in shadow; and the thousands of men who had had a part in the building’s design and construction were going to remember this day forever.

9 A.M.–9:33 A.M.

The police barricades had been stacked in the Tower Plaza since dawn that Friday morning. Now city employees were setting them out in neat straight lines. As yet no crowd had gathered.

The sky was clear, blue, limitless. A gentle harbor breeze swept the plaza, salt-smelling, fresh. The plaza flags rippled, two on-duty patrolmen—more would be arriving during the next hour—stood by the arcade.

“At least,” Patrolman Shannon was saying, “we’ve nothing political to cope with today, thank God for that. A political rally—” He shook his head. “The way some people in this country get stirred up over politics is a sin and a shame and a waste.” He glanced upward at the towering, gleaming building. “It reaches almost to Heaven,” he said. “Way above men’s little squabbles.” Patrolman Barnes said, “Dig the uninvolved man.” Patrolman Barnes was black. “To hear him tell it, all Irishmen are peaceable, loving, patient, unexcitable kind, considerate, and totally nonviolent.” Barnes had his master’s degree in sociology, was already marked down for promotion to sergeant, and had his sights set on a captaincy at least. He grinned at Shannon. “Those love-ins they stage over in Londonderry, friend, are not what you might call church socials.”

“Only when provoked,” Shannon said. He allowed himself a faint answering smile. “But I’m not saying that sometimes the provocation doesn’t have to be looked for. Sometimes it hides, like a mouse in a hole.” The smile disappeared as a man approached. “And where do you think you’re going?”

It was established later that the man’s name was John Connors. He carried a toolbox. In testimony Barnes and Shannon agreed that he had worn work clothes and a shiny aluminum hard hat and the kind of arrogance a skilled workman is tempted to show toward those who ask silly questions.

“Where does it look like I’m going? Inside.” Connors paused. His smile pitied them. “Unless you’re going to try to keep me out?” There was challenge in the question.

“There’s no work today,” Barnes said.

“I know it.”

“Then?’

Connors sighed. “Where I ought to be is home. In bed. A day off for everybody while they make speeches here and go upstairs to drink champagne. Instead, here I am because the boss called me and told me to haul my ass down to the job.”

“To do what?” This was still Barnes.

“I’m an electrician,” Connors said. “Would you understand what I’m supposed to do if I told you?”

Probably not, Barnes thought. But that was not the governing factor. The trouble was orders, or lack of them.

“You and Shannon,” the duty sergeant had said, “get on down there and keep an eye on things. They’ll be setting up the lines and we don’t expect any trouble, but—” The sergeant had shrugged with a you-know-how-it-is expression.

And they did know how it was these days: every gathering seemed to generate its own unrest. All right, they would keep an eye on things, but that scarcely included keeping a workman away from his work.

Читать дальше