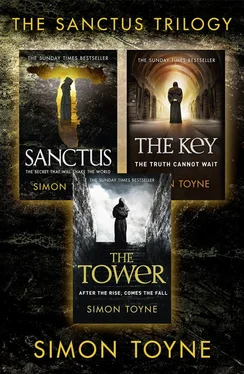

BESTSELLING CONSPIRACY THRILLER TRILOGY: Sanctus, The Key, The Tower

Simon Toyne

In the last week of May 2006 I decided to burn my life down.

The weather was warm, the sky was blue, and to the casual observer it probably seemed that my world did not particularly need torching. I was thirty-eight, had worked as a producer, director and writer in television for almost twenty years and in that time I had travelled the world, won some awards, made a good living and carved a fairly decent if unspectacular career. I had a lovely wife, a funny, clever little three year old with blonde ringlets and huge green eyes, and my baby boy had just been born. And it was the baby, in the end, that made me reach for the matches.

At the time of his birth I was producing a sort of talent show for inventors called ‘The Big Idea’, which was about as good as it sounds. And because it was live and because when you’re employed by someone else you have to do what they tell you, I wasn’t allowed to take any time off. My son had just been born and I couldn’t be there, not for him, not for my wife and not for my daughter, whose world had been invaded by a tiny, bald, crying thing.

I managed to sneak a few days at home – most of which I spent on the phone to the production office – and as I juggled a sleeping baby and a phone so hot it was cooking my ear, just to make a programme no one was going to see, I felt a growing sense of anger and frustration. I could sense the ghost of my eighteen-year-old self, watching me from the shadows, his brow knitted in fury and confusion, his unlined face incredulous at what he had become. That version of me had envisaged novels and film scripts and movies in his future. That version had a deep love of language and a desire to use it to tell stories, big stories on grand, vivid canvasses. He had not imagined arriving at the sharp end of thirty to find himself writing weak jokes about nerds in sheds for a cable channel. Something had to change. A bonfire needed to be built around all the pointless stuff I had somehow exchanged his dreams for.

The first thing I did was talk it all through with my wife, who, being lovely, realised that I was deeply unhappy and needed to do something about it, even though we now had two small mouths to feed as well as too big a mortgage on a house that was not quite big enough. She did a deal with me. She said she’d give me five years or three books to try and make a go of it. In that time I would spend six months of each year writing and the other six doing freelance TV jobs to bring some money in. Suddenly there was light in my professional darkness. We started saving and I began to think about what sort of story I was going to write. I also began to read lots of thrillers.

I have always loved thrillers, I love the mechanics of them and the addictive nature of reading a good one. The narrative structure of commercial television is not dissimilar. In both you have to grab the reader or viewer and hold on to them as tightly as you can, constantly re-engaging them and staying one or two steps ahead.

I discovered Lee Child, who was not quite so well known then. I remember burning through Killing Floor (his debut), then discovering that he was English and had worked for twenty years in British commercial television before writing his first novel. I took this to be a sign and carried on plotting and building my fire.

I also read a lot of advice for first time novelists, most of which seemed to agree that the best thing to do was to write what you know, stick close to your own experience so you can just concentrate on the writing. With this in mind I started developing a couple of ideas, both of which were contemporary thrillers revolving around an ordinary man, a bit like me, who is thrust into extraordinary situations. I figured this way I could keep my research to a minimum and make the most of the six months I planned to spend writing.

Then I struck the match and quit my job.

My bosses offered me a sabbatical but I turned it down, knowing that writing a book would be hard and having a safety net would make it easier to give up. I had read an interview with Lee Child where he’d said he’d written his first book as if his life depended on it. I could see the wisdom in that. I needed to do the same thing if I wanted to have the slightest chance of succeeding. And if I ultimately failed, I wanted it to be an honest failure with no excuses. That way I could at least look my eighteen-year-old self in the eye and say ‘Listen, we gave it our best shot. We just weren’t good enough.’

So, at the end of November 2007, I found myself aged thirty-nine with no job, sitting behind the wheel of a second-hand white transit van packed mostly with children’s books and toys. I was parked at the Newhaven ferry terminal waiting to board the midnight ferry. My wife was behind me in our car, also packed with various worldly goods. As part of the ‘burning down our life to see what was left’ pledge we had decided to rent out our flat in England and go and live in France for six months. The kids were still young enough for school terms not to be a problem and I figured if I was going to spend more time with my family I might as well do it somewhere exotic.

We were travelling in November because it’s much cheaper to rent somewhere in France in the winter than it is in the summer and the money we had saved needed to last. The plan was for my wife and I to sleep during the night crossing then drive for eight hours to our rented house in the Tarn and fill it full of familiar things in time for the arrival of our kids a couple of days later, who were flying over with friends.

Unfortunately we sailed into a force eight gale, which battered the ferry and ensured we got no sleep at all. We arrived in Dieppe in no shape to attempt an eight-hour drive, so we headed to Rouen instead, looking for a cheap hotel. And as we drove into the outskirts of the city, and dawn began to lighten the sky, I saw the spires of Rouen Cathedral and a Ralph Waldo Emerson quote I had always liked popped into my head. ‘A man is a god in ruins’. It could have been my tiredness, or the sense-sharpened state you can only achieve by stepping out of a comfortable place, but something about the spires and that quote meshed together to form the seed of a new idea.

We got some sleep and set off again, and the radio promptly broke in the van leaving me in silence for the entire eight-hour drive. And in that silence I kept thinking about the silhouette of the cathedral and the quote. By the time we got to the house that was going to be home for the next six months I had the framework of what eventually became Sanctus . It wasn’t small and semi-autobiographical. It was big, really big, with the whole of human history as its back-story and the end of days as its conclusion. It would require extensive research and ultimately the construction of an entire city, architecture, history and all. In short, it was not the sort of book I had intended to write – it wasn’t even the sort of book I thought I was capable of writing – but it was by far the best idea I had, so I started writing it.

We had a glorious six months, hanging out with each other, having winter fires then barbeques outside when the weather started to turn. The neat twisted lines of dead-looking sticks in the fields around us sprouted green fuzz then flowers then miniature bunches of hard, green grapes. The cherry crop came like a sugary wave that we bottled and made into jam and ate straight from the trees, and then the figs started to ripen and the grapes began to darken and swell. And when the money ran out and we had to come home I had written the first hundred and eighty pages of a book I called Ruin after the city I’d made up.

Читать дальше