The chopper pilot said, “Well give it a try.” He shrugged. “How close I can get, I don’t know. You get anywhere near these goddam tall buildings, and the wind—” He shook his head. “It blows in every direction at once, you know what I mean?”

The chief’s face was expressionless.

“Look,” the chopper pilot said, “I don’t mean to make a big thing out of it, but if we bang into that building, it isn’t going to do anybody any good, is it?”

The chief’s head moved a fraction of an inch in acknowledgment of the point. His expression did not change.

“You know about Hell Gate?” the pilot said. “Water from the Sound coming in, meeting the Harlem River, those whirlpools, crisscross currents?”

“I know Hell Gate,” the chief said. He had seen small craft completely out of control in Hell Gate waters, powerless to maneuver against the force of the currents, slammed against bridge pilings, against walls.

“Same thing in the winds around these big goddam buildings,” the pilot said. He paused. “All I’m saying is that we’ll give it a try, but I can’t promise anything.”

“Okay,” the chief said. “Kronski, get into that thing.”

“Thanks a lot,” Kronski said.

Nat stood in the doorway of the trailer, looking up. Nothing yet. Waiting was the hard part—now who had said that? But it was true, and he had never realized it before. You have an idea and you set it in motion, and then you wait, and hope, because there is nothing else to do.

“It will work,” Patty said. She smiled. “It has to.”

6:24–6:41

With the windows broken out it was perceptibly cooler in the Tower Room, although, as some noticed with mounting alarm, the flow of smoke from the air-conditioning ducts was also increasing.

“Cause and effect, probably,” Ben Caldwell explained again. “As long as this was a more or less sealed chamber, the flow of smoke, or air, through the ducts was limited. Now with the broken-out windows acting as vents—” He spread his hands and shrugged.

Henry Timms, the network president, said, “Then we shouldn’t have allowed the windows to be broken.” His voice was assured, decisive, and critical. “There was obviously little chance that a line could be shot here.” Caldwell said merely, “It isn’t entirely black-and-white,” and turned away.

He was an architect, a designer, and in his view life was rarely black-and-white. He detested even the word compromise, but he was also aware that the accommodations it spoke for were all that made most enterprises possible. The choice here had been between the chance that a line could be shot from the Trade Center tower and the certainty that more smoke would be brought in. As far as the decision was concerned, he was happy to leave it to others. He could not have cared less.

He supposed that a majority of people in the room still entertained some hope. He did not. He was used to facing tangible facts, attempting to avoid them was exercise in futility. How deep the eventual damage to the building’s structure was going to be he could not begin to estimate, but long before the damage was complete, everyone in this room was going to be dead. He had long ago resigned himself to that. And it no longer had the power to bother him because a large part of himself had already died.

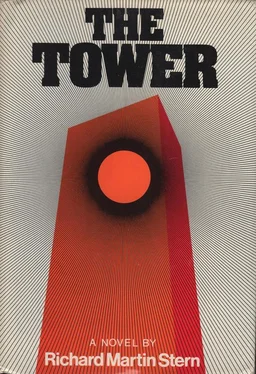

This was his building, his vision, his soaring dream. And now it was ruined.

On whose shoulders lay the ultimate blame he had no idea. Nor did he particularly care. What difference whose hand had wielded the hammer that disfigured the Pieta? Oh, society might wish to take revenge, but nothing could restore the work of art.

In New York, in Los Angeles, in Chicago, in Pittsburgh and a dozen lesser cities he had his monuments, and they would stand long after he was gone. But this building was —had been —his masterpiece, and it was now beyond redemption; visions, calculations, compromises, labor, love, all the blood, sweat, and tears of the process of achievement—for nothing.

When he stood in his office this morning, the pile of change orders lying on his desk, Nat Wilson summoned, had he felt then the first intimation of disaster? Hard to tell; hindsight was always suspect. No matter. The disaster was now taking shape.

Senator Peters walked up, wearing his crooked smile. “Deep in reverie,” he said. “Ideas?”

Caldwell shook his head. “Regrets only.”

“That sounds like an invitation to a party.”

Caldwell’s tight little smile was expressive. “For this party, I am afraid, there will be no regrets.”

“So I understand.” The senator paused. “It doesn’t seem to bother you.”

“Does it you?”

“You know,” the senator said, “I’ve been trying to find the answer to that for some time. I’m not sure.” He made a deprecatory gesture. “Oh, I don’t mean that I’m above any fear of death. I’m not. What I do mean is something entirely different.”

“Such as?” Despite himself, Caldwell was interested. “Some kind of faith?”

The senator smiled. “Not in any. established sense. I have always been a heathen. No”—he shook his head—“it’s part, I suppose, of a lifetime of learning that some things can’t be avoided, some battles can’t be won, some decisions have to be accepted—”

“In a word,” Caldwell said, “politics? The art of the possible?”

The senator nodded. “We’re shaped by what we do.” He smiled. “Bent couldn’t shuck the habit of command if he tried. He’s like a veteran airplane pilot, uncomfortable when anybody else is at the controls.”

More and more interesting. “And Paul Norris?” Caldwell said. “Grover Frazee? How do you explain their behavior?”

The senator smiled. “I’ll tell you a story about Paul Norris. At college he had a fine suite of rooms in Adams House. His bedroom window looked right out at the campanile of the Catholic church. Some of us had an idea and Paul went along. We mounted an air rifle on the window sill in a steady rest aimed at the bell tower. At midnight when the church bell struck twelve, we pulled the trigger and the bell struck thirteen.”

Caldwell was smiling now, nodding, in this moment taken back forty years to youthful fervor. “Go on.”

“We did it again the second night,” the senator said. “A couple of Catholics who lived in Adams House attended Ma-s and reported that the good fathers were understandably puzzled, even mildly upset. There was talk of a miracle.” The senator paused. “The third night the bishop came over from Boston to listen for himself. We didn’t disappoint him. The clock struck thirteen. Then we dismantled the steady rest and took the air rifle away.”

Caldwell, smiling still, said, “But what about Paul Norris?”

The senator shook his head. “He wanted to keep it up. Night after night. He couldn’t see that it was best left right there—a mystery. Among other unpleasant things about Paul, he was stupid, and I don’t like to waste time arguing with stupid people.” He paused again. “Although, God knows, a politician can’t ever hope to avoid it.” Caldwell said, “You said part of your—acceptance was that some things couldn’t be avoided, some decisions had to be accepted. What other parts?”

“I suppose,” the senator said slowly, “that I have a sniggly feeling it’s all for the best. Don’t ask me how, because I can’t give even a rational theory.” He paused. “Do you recall,” he said, “that in Athens, when things went wrong, the king had to die? Theseus’s father threw himself off the cliff because the black sails on Theseus’s ship indicated that things had gone wrong.” His smile was apologetic. “Maybe we’re a mass sacrifice? Ridiculous idea, isn’t it?”

Читать дальше