‘I’ve seen these around town,’ he said – posh Edinburgh tones – keeping his voice low as if fearing being told off.

The other stranger examined the stencil, and his smile broadened. ‘You want to be the next Banksy?’

‘There was a story in the papers,’ the second stranger said. ‘Police seemed very keen to talk to the artist responsible…’

‘That’s the anti-establishment stance I was talking about.’ The first stranger faced Westie again and waited for him to say something. This time, Westie decided to oblige.

‘So you want me to copy a painting?’ he blurted out.

‘Half a dozen, actually,’ Gissing corrected him. ‘All of them from the national collection.’

‘And it’s to be done without anyone knowing?’ Westie’s eyes were widening. Was he stoned and imagining this whole thing? ‘They’ve been stolen, is that it? And the gallery doesn’t want any of the public to get an inkling…’

‘I told you he was smart.’ The visitor was leaning the Stubbs back against the skirting board. ‘Now then, Westie, if we’ve whetted your appetite, maybe we can take you to the professor’s office and show you just exactly what we’re after…’

The four of them sat at individual desks in Robert Gissing’s room. He still gave occasional tutorials, hence the chairs with writing surfaces attached. His secretary had left for the day – at Gissing’s request. Mike and Allan had eventually introduced themselves to Westie by their first names, having decided that it would be too cumbersome to use aliases. After all, it wasn’t as though Gissing could use one, and if Westie went to the police with the professor’s name, it wouldn’t take a Columbo or a Frost to connect Mike and Allan with him.

Mike wasn’t sure why Allan had said so little back in Westie’s flat – cold feet, perhaps, or maybe it was because Mike had already stated his intention to bankroll the operation. Stood to reason they’d need funds, and Mike was the one with cash to spare. For a start, he was sure Westie would need paying – payment for his silence, as well as his expertise.

At this stage, of course, it was still a game they were playing. Making the copies didn’t mean they had to take the scheme any further. Allan had seemed to accept this, but maybe also thought that Mike, being willing to pay for the privilege, should be the one to do the talking.

‘Whatever I end up forking out, I might still be getting a masterpiece on the cheap,’ Mike had assured him.

‘Not that we’re doing this for the money,’ Gissing had growled.

The professor’s room was chaotic. He had already cleared some of his bookshelves into boxes in preparation for retirement. There was a stack of mail on his desk, along with a computer and an old golfball-style typewriter. More books were heaped either side of the desk, and piles of art magazines were threatening to topple. The walls were cluttered with prints by Giotto, Rubens, Goya and Brueghel the Elder – these were the ones Mike recognised. There was a dusty CD player on one shelf and half a dozen classical titles. Von Karajan seemed to be the conductor of choice.

The blinds had been closed, leaving the room in semi-darkness. A screen had been pulled down from the ceiling immediately in front of the bookcases, so that Gissing could show them a wide selection of slides from the collection of the National Galleries, everything from Old Masters to Cubism and beyond. On the way over, Mike had explained a little more of the plan to Westie, who had slapped his knees, laughing with glee. Maybe it was just the dope kicking in.

‘If I can help, count me in,’ he’d said between gulps of air.

‘Don’t be too hasty,’ Mike had cautioned. ‘You need to think things through.’

‘After which, if you still want in,’ Gissing had added, ‘you’ll have to start taking it a bit more seriously.’

Now, as they looked at the slides, Westie slurped cola from a vending machine can. He sat forward in his chair, both knees pumping.

‘I could do that,’ was his refrain as the slides came and went.

Gissing, Allan and Mike had already pored over the slides, all of them showing items held in the overflow warehouse. Where possible, Gissing had found reproductions on paper to accompany them. These sat on the various desks, but Mike and Allan felt no need to study them further – they had already chosen a couple of favourites apiece, as had Gissing himself. But they needed to be confident that the young artist would cope with the different styles and periods.

‘Now, how would you begin here?’ Gissing asked, not for the first time. Westie’s mouth twitched and he began drawing shapes in the air as he explained.

‘Monboddo’s actually pretty straightforward if you’ve studied the Scottish Colourists – nice big flat brush, laying the oil on in thick swirls. He’ll go over one colour with another, and then another after that so you’re left with hints of what was there before. Bit like pouring cream on to coffee where you can still glimpse the black through the white. He’s after harmony rather than contrast.’

‘That sounds like a quote,’ Gissing commented.

Westie nodded. ‘It’s George Leslie Hunter – from your lecture on Bergson.’

‘Would you need special brushes, then?’ Mike interrupted.

‘Depends how thorough you want me to be.’

‘You need to defeat the naked eye, the gifted amateur…’

‘But not the forensic specialist?’ Westie checked.

‘That’s not an immediate concern,’ Gissing reassured him.

‘It would be nice if we had access to the right papers and ages of canvas… brand new canvas looks just that – brand new.’

‘But you have ways…?’

Westie gave a grin and a wink at Mike’s question. ‘Look, if an expert comes along, they’ll spot the difference in a few minutes. Even an exact copy isn’t an exact copy.’

‘A point well made,’ Gissing muttered, rubbing a hand over his forehead.

‘Yet some forgers get away with it for years,’ Mike offered.

Westie shrugged his agreement. ‘But these days, with carbon dating and Christ alone knows what else waiting in the wings… don’t tell me you’ve not watched an episode of CSI?’

‘The thing we need to keep reminding ourselves, gentlemen,’ Gissing said, removing the hand from his forehead, ‘is that nothing is going to be missing, meaning there’s no reason for any of these boffins to become involved.’

Westie chuckled, not for the first time. ‘Got to say it again, Professor – it’s mad but brilliant.’

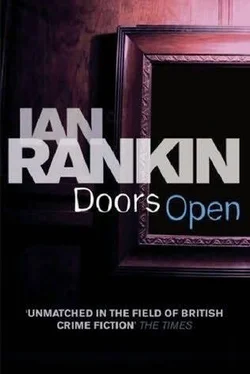

Mike was forced to agree: walk into the warehouse on Doors Open Day and replace the real paintings with Westie’s carefully crafted copies. It sounded simple, but he knew it would be anything but. There was a lot of planning still ahead of them…

And plenty of time to pull out.

‘We’re like the A-Team for unloved artworks,’ Westie was saying. He had calmed a little – only one knee was pumping as he drained the can of cola – but was no longer concentrating on the slideshow. He turned in his chair to face Mike. ‘Look, none of this is really going to happen, right? It’s like Radiohead might say – a nice dream. No disrespect, but you three are what I’d call establishment guys of a certain age and cut. You’re suits and ties and corduroy, nights at the theatre and supper afterwards.’ He leaned back in his chair and crossed one busy leg over the other, concentrating on the wagging motion of a paint-spattered trainer. ‘You’re not master criminal material, and no way can you pull off something like this without a bit more firepower.’

Secretly, Mike had been thinking the selfsame thing, but he didn’t let it show. ‘That’s our problem, not yours,’ he said instead. Westie nodded slowly.

Читать дальше