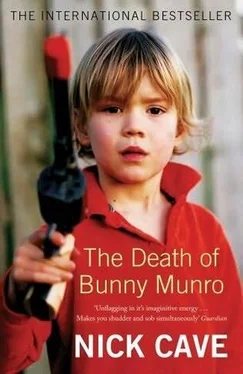

Bunny sighs and wonders what he is doing. Then it comes to him – he is here to sell stuff. He closes his eyes and composes himself and approximates a person who has charm and who is in control. This is not as easy as it sounds because Bunny feels, in an oblique way, that a kind of lunacy has come to visit and decided to stay until all the lights go out. ‘I’m looking for a Mrs Candice Brooks,’ he says.

With an arthritic and bejewelled hand, the old lady adjusts her glasses and says, ‘Yes, I’m Mrs Brooks. What can I do for you, young man?’

Bunny thinks – Young man? Jesus, is she blind? – then realises that actually she is. He silently cogitates whether this is, for him, an advantage or a disadvantage. He decides on the former due to his inherent optimism.

‘Mrs Brooks, my name is Bunny Munro. I am a representative of Eternity Enterprises. You have contacted our central office and asked for a free demonstration of our range of beauty products.’

‘I did?’ says the old lady, her ringed fingers tapping and clacking around the edge of the door.

‘Your name is on our list, Mrs Brooks.’

‘Oh, I don’t doubt it, Mr Munro. Daresay I will forget to turn up to my own funeral,’ says the old lady, with a grim chuckle.

Mrs Brooks invites Bunny in and leads him through a small, sunless kitchen. Bunny thinks, as he checks out her swollen ankles and her support stockings, that chances are Mrs Candice Brooks will turn out to be a classic time-waster – a lonely old bird that just wants to talk. He remembers when he used to go out with his dad, who was in the antique business, and it was precisely this kind of good-natured biddy that his old man could really get his teeth into – that he could really squeeze . He was a master of it – a true charmer. But extorting them of their antique furniture was one thing, trying to sell them beauty products was another thing altogether.

‘I hope the new girl who comes to clean has left the place looking nice. I never really know. They come and go, these young things. They cost the earth and none of them really wants to be looking after a dotty old bat like me.’

‘Hired hindrance, Mrs Brooks,’ says Bunny, and Mrs Brooks chuckles as she taps her way through the kitchen with her white, cleated stick.

‘Exactly, Mr Munro,’ she says, as Bunny remembers, with a sudden plasmatic surge in his leopard-skin briefs, Mylene Huq from Rottingdean, bucking and screaming and begging Bunny to come on her face.

Bunny follows Mrs Brooks into the living room and it is heavy with dead air as if time itself had ossified into something immobile and unyielding. The shelves are crammed with ancient books covered in a patina of dust and there is the terrible spectral absence of a television set. The open-lidded, upright Bösendorfer along the far wall, with its rictus of flavescent teeth, would be a nice little earner for some enterprising antique dealer in a couple of years – thinks Bunny – and he gestures pointlessly at the piano and enquires of the old blind lady, ‘Do you play?’

Mrs Brooks makes monster claws of her arthritic hands and giggles like a little girl. ‘Only on Hallowe’en,’ she says.

‘You are a very trusting lady. Do you always invite strangers into your home?’ asks Bunny.

‘Trusting? Nonsense! I have one foot firmly planted in the grave, Mr Munro. What would anyone want from me?’ and with her antenna-like stick clicking against the furniture, the old lady makes her way to the chintz-covered armchair and lowers herself into it.

‘You’d be surprised,’ says Bunny, looking at his watch and suddenly remembering an alcoholic dream he had had the night before that involved finding a matchbox full of celebrity clitorises – Kate Moss’s, Naomi Campbell’s, Pamela Anderson’s and of course Avril Lavigne’s (among others) – and trying unsuccessfully to stab holes in the lid with a blunt knitting needle while the little pink peas screamed for air.

‘I may be blind, Mr Munro, but my other senses have yet to desert me. You seem like a nice man.’

Mrs Brooks offers Bunny the chair opposite her and Bunny has the sudden urge to turn around and make a run for it – he feels a kind of foreboding in the room – but instead he sits and places his sample case on the little Queen Anne table in front of him. Bunny realises to his surprise that there is an oversized transistor radio on the table that has been playing classical music the whole time he has been there.

Mrs Brooks swoons dramatically, and then rocks back and forth and says, with great reverence, ‘Beethoven. Next to Bach, no one does it better. Streets ahead of Mozart. Beethoven understood suffering in the most profound way. You can feel his deep belief in God and his raging love for the world.’

‘It’s all a bit over my head,’ says Bunny. ‘I’m just a working stiff.’

‘Auden said it all. “We must love one another or die.”’

Mrs Brooks’ misshapen hands twitch on the armrests of her chair like alien spiders and her rings make an unsettling clicking sound. Outside Bunny can hear the bitching squawk of seagulls and the low drone of the seafront traffic.

‘Have you read Auden, Mr Munro?’

Bunny sighs and rolls his eyes and snaps open his sample case.

‘Bunny,’ he says. ‘Call me Bunny.’

‘Have you read Auden, Bunny?’

Bunny feels a needle of irritation tweak the nerve over his left eye.

‘Only on Hallowe’en, Mrs Brooks,’ says Bunny, and the old lady laughs like a little girl.

The Punto is parked on the Marine Parade and Bunny Junior rests his head on the window and watches the steady stream of people walking past and wonders exactly what it is he is doing. He feels like he has learned the Patience Law and wonders when his dad is going to teach him how to actually sell something. The boy thinks there may be a chance that not only is he going blind with advanced blepharitis, but he is going insane as well, and has looked up the word ‘Mirage’ in his encyclopaedia and it says ‘An optical illusion resulting from the refraction of light causing objects near the horizon to become distorted.’ He has also found ‘Apparition’ and it says ‘The visual experience of seeing a person (living or dead) not actually present,’ but none of this makes much sense to him. He has come to believe that his mother is looking for him and that she has something important to tell him, and he thinks that if he remains where he is she will, in time, find him. He is glad he has learned the Patience Law. It has been helpful. He also thinks that there is something that he has to tell his mother but he can’t think of what it is because he is too hungry. He wishes he had eaten his Cornish pasty in the café at lunchtime. He sees a group of youths mooch by, stuffing handfuls of chips into the holes in their hoods, and a hungering noise issues from the pit of his stomach.

He looks behind him and can see, across the road on the promenade, a booth with ‘FISH AND CHIPS’ written in large letters on its candy-striped awning. The sea breeze brings down a delirious waft of fried potatoes and vinegar and Bunny Junior closes his eyes and inhales and, once again, whatever the animal is that’s trapped in his guts lets out a demonstrative moan.

The boy knows he is not allowed to get out of the car but he is becoming increasingly worried that if he doesn’t eat something soon, he is going to die of hunger. He knows that he has three one-pound coins in the pocket of his trousers. He imagines, with a certain amount of pleasure, his father returning and finding him dead in the Punto. What would that say about his Patience Law? The boy sits there and counts to one hundred. He looks over one shoulder then the other. He opens the door of the Punto and climbs out, jiggling the coins in his pocket.

Читать дальше