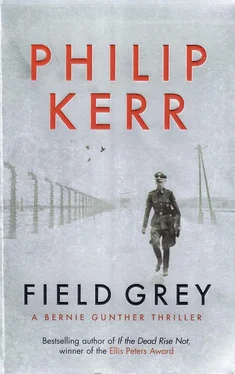

Philip Kerr - Field Grey

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Philip Kerr - Field Grey» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Жанр: Триллер, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Field Grey

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:3 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Field Grey: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Field Grey»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Field Grey — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Field Grey», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

'I'm working,' I said. 'Like anyone else.'

'You think so? When was the last time a Blue shouted at you to hurry up? Or called you a German pig?'

'Now you come to mention it, they have been rather more polite of late.'

'Eventually the other plenis will forget what you did for them and remember only that you are preferred by the Blues. And they'll conclude that there's more to it than meets the eye. That you're giving the Blues something else, in return.'

'But that's nonsense.'

'I know it. You know it. But do they know it? In six months from now you'll be an anti-fascist agent in their eyes, whether you are or not. That's what the Russians are gambling on. That as you are shunned by your own people you have no choice but to come over to them. Even if that doesn't happen, one day you'll have an accident. A bank will give way for no apparent reason and you'll be buried alive. But your rescue will come too late. And if you are rescued then you'll have no choice but to take Gebhardt's place. That is if you want to stay alive. You're one of them, my friend. A Blue. You just don't know it yet.'

I knew Pospelov was right. Pospelov knew everything about life at KA He ought to have done. He'd been there since Stalin's Great Purge. As the music teacher to the family of a senior Soviet politician arrested and executed in 1937, Pospelov had received a twenty-year sentence – a simple case of guilt by association. But for good measure the NKVD – as the MVD was then called – had broken his hands with a hammer to make sure that he could never again play the piano.

'What can I do?' I asked.

'For sure you can't beat them.'

'You can't mean that I should join them, surely?'

Pospelov shrugged. 'It's odd where a crooked path will sometimes take you. Besides, most of them are just us with blue shoulder boards.'

'No, I can't.'

'Then you will have to watch out for yourself, with all three eyes, and by the way, don't ever yawn.'

'There must be something I can do, Ivan Yefremovich. I can share some of my food, can't I? Give my warmer clothing to another man?'

"They'll simply find other ways to show you favour. Or they'll try to persecute those that you help. You must really have impressed that MVD major, Gunther.' He sighed and looked up at the grey-white sky and sniffed the air. 'Any day now it will snow. The work will be tougher then. If you're going to do anything it would be best to do it before the snow when days and tempers are shorter and the Blues hate us more for keeping them outside. In a way, they're prisoners just like we are. You've got to remember that.'

'You'd see the good in a pack of wolves, Pospelov.'

'Perhaps. However, your example is a useful one, my friend. If you wish to stop the wolves from licking your hand, you will have to bite one of them.'

Pospelov's advice was hardly welcome. Assaulting one of the guards was a serious offence – almost too serious to contemplate – and yet I didn't doubt what he had told me: if the Ivans kept on giving me special treatment I was going to meet with a fatal accident at the hands of my comrades. Many of these were ruthless Nazis and loathsome to me, but they were still my fellow countrymen and, faced with the choice of keeping faith with them or joining the Bolsheviks to save my own skin, I quickly formed the conclusion that I'd already stayed alive for longer than I might otherwise have expected and that maybe I had no choice at all. I hated the Bolsheviks as much as I hated the Nazis; under the circumstances, perhaps more than I hated the Nazis. The MVD was just the Gestapo with three Cyrillic letters, and I'd had enough of everything to do with the whole apparatus of state security to last me a lifetime.

Clear in my mind what I had to do and, in full view of almost every pleni in the half-excavated canal, I walked up to Sergeant Degermenkoy and stood right in front of him. I took the cigarette from the mouth in his astonished-looking face and puffed it happily for a moment. I discovered I didn't have the guts to hit him but managed to find it in me to knock the blue-banded cap off his ugly tree stump of a head.

It was the first and only time I heard laughter at KA And it was the last thing I heard for a while. I was waving to the other plenis when something hit me hard on the side of head – perhaps the stock of Degermenkoy's sub-machine gun – and probably more than once. My legs gave way and the hard, cold ground seemed to swallow me up as if I'd been water from the Volga. The black earth enveloped me, filling my nostrils, mouth and ears, and then collapsed altogether, and I fell into the dreadful place that the Great Stalin and the rest of his murderous Red gang had prepared for me in their socialist republic. And as I fell into that endless deep pit they stood and waved at me with gloved hands from the top of Lenin's mausoleum while all around me there were people applauding my disappearance, laughing at their own good fortune, and throwing flowers after me.

I suppose I should have been used to it. After all, I was accustomed to visiting prisons. As a cop I'd been in and out of the cement to interview suspects and take statements from others. From time to time I'd even found myself on the wrong side of the Judas hole: once in 1934, when I'd irritated the Potsdam police chief; and again, in 1936, when Heydrich had sent me into Dachau as an undercover agent, to gain the trust of a small-time criminal. Dachau had been bad, but not as bad as Krasno-Armeesk, and certainly not as bad as the place I was in now. It wasn't that the place was dirty or anything; the food was good; they even let me have a shower and some cigarettes. So what was it that bothered me? I suppose it was the fact that I was on my own for the first time since leaving Berlin in 1944. I'd been sharing quarters with one or more Germans for almost two years and now, all of a sudden, there was only myself to talk to.

The guards said nothing. I spoke to them in Russian and they ignored me. The sense of being separated from my comrades, of being cut off, began to grow and, with each day that passed, became a little worse. At the same time I had an awful feeling of being walled in – again, this was probably a corollary of having spent so much of the last six months outside. Just as the sheer size of Russia had once left me feeling overwhelmed, it was the very smallness of my windowless cell – three paces long and half as wide – that began to weigh on me. Each minute of my day seemed to last for ever. Had I really lived for as long as I had with so little to show for it in the way of thoughts and memories? With all that I had done I might reasonably have expected to have occupied myself for hours with a remembrance of things past. Not a bit of it. It was like looking down the wrong end of a telescope. My past seemed wholly insignificant, almost invisible. As for the future, the days that lay ahead of me seemed as vast and empty as the steppes themselves. But the worst feeling of all was when I thought of my wife; just thinking of her at our little apartment in Berlin, supposing it was still standing, could reduce me to tears. Probably she thought I was dead. I might as well have been dead. I was buried in a tomb. And all that remained was to die.

I managed to mark the passing time on the porcelain tile walls with my own excrement. And in this way I noted the passing of four months. Meanwhile I put on some weight. I even got my smoker's cough back. Monotony dulled my thinking. I lay on the plank bed with its sackcloth mattress and stared at the caged light bulb above the door wondering how long they gave you for knocking a Blue's hat off. Given the immensity of Pospelov's crime and punishment, I came to the conclusion that I might expect anything between six months and twenty-five years. I tried to find in me something of his fortitude and optimism, but it was no good: I couldn't help but recall something else he said. A joke he made once, only with each passing day, it felt less and less like a joke and more like a prediction.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Field Grey»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Field Grey» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Field Grey» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.