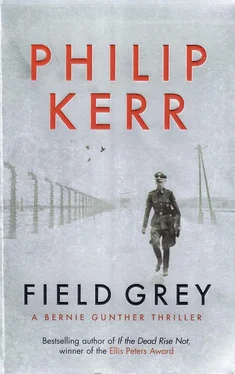

Philip Kerr - Field Grey

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Philip Kerr - Field Grey» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Жанр: Триллер, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Field Grey

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:3 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Field Grey: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Field Grey»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Field Grey — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Field Grey», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

'No, sir. I was always in uniform. Which means if I had been a spy I'd have been a rather stupid one. And as I told you already, sir, I was in intelligence. It was my job to monitor Russian radio broadcasts, read Russian newspapers, speak to Russian prisoners…'

'Did you ever torture a Russian prisoner?'

'No, sir.'

'A Russian would never give information to fascists unless he was tortured.'

'I expect that's why I never got any information from Russian prisoners, sir. Not once. Not ever.'

'So what makes the SGO think that you can get it from German plenis?'

'That's a good question, sir. You would have to ask him that.'

'His brother is a war criminal. Did you know that?'

'No, sir.'

'He was a doctor at Buchenwald concentration camp,' said Major Savostin. 'He carried out experiments on Russian POWs. The colonel claims not to be related to this person, but it's my impression that Mrugowski is not a common name in Germany.'

I shrugged. 'We can't choose the people to whom we are related, sir.'

'Perhaps you are also a war criminal, Captain Gunther.'

'No, sir.'

'Come now. You were in the SD. Everyone in the SD was a war criminal.'

'Look, sir, the SGO asked me to look into the murder of Wolfgang Gebhardt. He gave me the strange idea that you wanted to find out who did it. That if you didn't find out, then twenty-five of my comrades were going to be picked out at random and shot for it.'

'You were misinformed, Captain. There is no death penalty in the Soviet Union. Comrade Stalin has abolished it. But they will stand trial for it, yes. Perhaps you yourself will be one of these men picked at random.'

'So, it's like that, is it?'

'Do you know who did it?'

'Not yet. But it sounds like you just handed me an extra incentive to find out.'

'Good. We understand each other perfectly. You're excused work for the next three days in order that you may solve the crime. I will inform the guards. How will you start?'

'Now that I've seen the body, by thinking. That's what I normally do in these situations. It's not very spectacular but it gets results. Then I'd like permission to interview some of the prisoners, and perhaps some of the guards.'

'The prisoners, yes, the guards, no. It wouldn't be right to have a good communist being cross-questioned by a fascist.'

'Very well. I'd also like to interview the surviving anti-fa agent, Kittel.'

'This I will have to think about. Now then, it would not be appropriate for you to interview the other prisoners while they're working. So you can use the canteen for that. And for thinking, yes, it might be best if you were to use Gebhardt's hut. I'll have the body removed immediately if you're finished with it.'

I nodded.

'Very well then. Please follow me.'

We walked to Gebhardt's hut. Halfway there Savostin saw some guards and barked some orders in a language that wasn't Russian. Noticing my curiosity, he told me that it was Tatar.

'Most of these pigs who guard the camp are Tatars,' he explained. 'They speak Russian, of course, but to make yourself clear you really have to speak Tatar. Perhaps you should try to learn.'

I didn't answer that. He wasn't expecting me to. He was too busy looking around at the huge building site.

'Just think,' he said. 'All of this will be a canal by 1950. Extraordinary.'

I had my doubts about that, which Savostin seemed to sense. 'Comrade Stalin has ordered it; he said, as if this was the only affirmation needed.

And in that place, and in that time, he was probably right.

When we reached Gebhardt's hut he supervised the removal of the body.

'If you need anything,' he said, 'come to the guardhouse.' He looked around. 'Which is where exactly? I'm not at all familiar with this camp.'

I pointed to the west, beyond the canteen. I felt like Virgil pointing out the sights in Hell to Dante. I watched him walk away and went back into the hut.

The first thing I did was to turn over the mattress, not because I was looking for something but because I intended to have a sleep and I hardly wanted to lie on top of Gebhardt's bloodstains. No one ever had enough sleep at KA, but thinking's no good if you're tired. I took off his jacket, lay down and closed my eyes. It wasn't just lack of sleep that made me tired, but the vodka, too. The deflated football that was my stomach wasn't used to the stuff any more than my liver was. I closed my eyes and went to sleep wondering what the Soviet authorities were likely to do to me and twenty-four others if the death penalty had indeed been abolished. Was it possible there was a worse camp than the ones I had already seen?

A while later – I've no idea how long I slept, but it was still light outside – I sat up. The cigarettes were still in my jacket pocket so I lit another, but it wasn't like a proper cigarette; there was a paper holder and only about three or four centimetres of tobacco – what the Ivans called a papirossi cigarette. These were Belomorkanal, which seemed only appropriate since that was a Russian brand introduced to commemorate the construction of another canal, this one connecting the White Sea to the Baltic. The Abwehr's opinion of the Belomorkanal was that it had been a disaster: too shallow, making it useless to most seagoing vessels, not to mention the tens of thousands of prisoners sacrificed on its construction. I wondered if this particular canal would fare any better.

I finished the cigarette and aimed the butt at Stalin, and something about the way it struck the great leader's nose made me get up and take a closer look at the paper portrait. When I tugged it off the wall I was surprised to see that the picture had neatly concealed a small shelved alcove, about the size of a book. On the shelf were a notebook and a roll of banknotes. It wasn't a wall safe, but in that place it was maybe the next-best thing.

The roll of banknotes was almost four hundred five 'gold' rouble notes – about three or four months' wages for a Blue. This wasn't a fortune, unless you were a pleni. Two thousand roubles plus a gold wedding band might just be enough to bribe some better treatment inside an MVD jail in Stalingrad. I looked at the roubles again, just to make sure, and to my relief they all had that greasy, authentically Russian feel about them. I even held the bills up to the light coming through the window to check the watermark before folding them into the back pocket of my uniform breeches, which was the only one with a button and without a large hole.

The notebook had a red cover and was about the size of an identity card. It was full of cheap Russian paper that looked more like something flattened by a heavy object and which contained a surprise all of its own, for on one page there was a name beneath which were written some dates and some payment details, and these seemed to indicate that the pleni named was in the pay of Gebhardt. Not that this made the pleni a murderer, exactly, but it did help to explain how it was that the Blues were able to police the POWs so effectively.

But the date of one particular payment caught my eye: Wednesday August 15th. This was the Feast of the Assumption of Mary, and for some Catholic Germans, especially those from

Saarland or Bavaria, it was also an important public holiday. But nearly everyone in camp remembered this as the day when Georg Oberheuser – a sergeant from Stuttgart – had been arrested by the MVD. Angry that this date was to be treated as a normal working day, Oberheuser had loudly denounced Stalin to everyone in our hut as a 'wicked, godless bastard'. There were other no less slanderous epithets he used as well, and all of them well deserved, no doubt, but we were all a little bit shaken when Oberheuser was taken away and never seen again, and by the knowledge that with no Ivans in our hut, Oberheuser had to have been betrayed to the Blues by another German.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Field Grey»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Field Grey» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Field Grey» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.