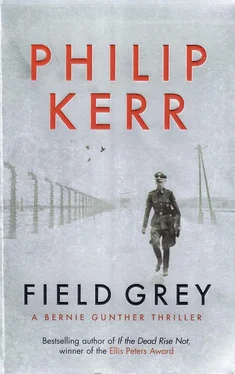

Philip Kerr - Field Grey

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Philip Kerr - Field Grey» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Жанр: Триллер, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Field Grey

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:3 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Field Grey: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Field Grey»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Field Grey — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Field Grey», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

'The first ten years are always the hardest,' he said.

I was haunted by that remark.

Most of the time I hung on to the certainty that before I was sentenced there would have to be a trial. Pospelov said there was always a trial, of sorts. But when the trial came it was over before I knew it.

They came and took me when I least expected it. One minute I was eating my breakfast, the next I was in a large room being fingerprinted and photographed by a little bearded man with a big box range-finder camera. On top of the polished wooden box was a little spirit level – a bubble of air in a yellow liquid that resembled the photographer's watery, dead eyes. I asked him several questions in my best, most subservient Russian, but the only words he used were 'Turn to the side' and 'Stand still please'. The please was nice.

After that I expected to be taken back to my cell. Instead I was steered up a flight of stairs and into a small tribunal room. There was a Soviet flag, a window, a large hero wall featuring the terrible trio of Marx, Lenin and Stalin, and, up on a stage, a table behind which were sitting three MVD officers, none of whom I recognised. The senior officer, who was seated in the middle of this troika, asked me if I required a translator, a question that was translated by a translator – another MVD officer. I said I didn't but the translator stayed anyway and translated, badly, everything that was said to or about me from then on. Including the indictment against me, which was read out by the prosecutor, a reasonable-looking woman who was also an MVD officer. She was the first woman I'd seen since the march out of Konigsberg and I could hardly keep my eyes off her.

'Bernhard Gunther,' she said, in a tremulous voice – was she nervous? Was this her first case? 'You are charged-'

'Wait a minute,' I said, in Russian. 'Don't I get a lawyer to defend me?'

'Can you afford to pay for one?' asked the chairman.

'I had some money when I left the camp at Krasno-Armeesk,' I said. 'While I was being brought here it disappeared.'

'Are you suggesting it was stolen?'

'Yes.'

The three judges conferred for a moment. Then the chairman said, 'You should have said this before. I'm afraid these proceedings may not be delayed while your allegations are investigated. We shall proceed. Comrade Lieutenant?'

The prosecutor continued to read out the charge: 'That you wilfully and with malice aforethought assaulted a guard from Voinapleni camp number three, at Krasno-Armeesk, contrary to martial law; that you stole a cigarette from the same guard at camp number three, which is also against martial law; and that you committed these actions with the intent of fomenting a mutiny among the other prisoners at camp three, also contrary to martial law. These are all crimes against Comrade Stalin and the peoples of the Union of the Soviet Socialist Republics.'

I knew I was in trouble now. If I hadn't realised it before I realised it now: knocking a man's hat off was one thing; mutiny was something else. Mutiny wasn't the kind of charge to be dismissed lightly.

'Do you have anything you wish to say in your defence?' said the chairman.

I waited politely for the translator to finish and made my defence. I admitted the assault and the theft of the cigarette. Then, almost as an afterthought I added, 'There was certainly no intention of fomenting a mutiny, sir.'

The chairman nodded, wrote something on a piece of paper – probably a reminder to buy some cigarettes and vodka on his way home that night – and looked expectantly at the prosecutor.

In most circumstances I like a woman in uniform. The trouble was this one didn't seem to like me. We'd never met before and yet she seemed to know everything about me: the very wicked thought processes that had motivated me to cause the mutiny; my devotion to the cause of Adolf Hitler and Nazism; the pleasure I had taken in the perfidious attack upon the Soviet Union in June 1941; my important part in the collective guilt of all Germans in the murders of millions of innocent Russians; and, not happy with this, that I'd intended to incite the other plenis at camp three to murder many more.

The only surprise was that the court withdrew for several minutes to reach a verdict and, more important, have a cigarette. Smoke was still trailing from the nostrils of one member of the tribunal as they came back into the room.

The prosecutor stood up. The translator stood up. I stood up. The verdict was announced. I was a fascist pig, a German bastard, a capitalist swine, a Nazi criminal; and I was also guilty as charged.

'In accordance with the demands of the prosecutor and in view of your previous record, you are sentenced to death.'

I shook my head, certain the prosecutor had made no such demands – perhaps she had forgotten – nor had my previous record been so much as mentioned. Unless you counted the invasion of the Soviet Union, and that much was true.

'Death?' I shrugged. 'I suppose I can count myself lucky I don't play the piano.'

Oddly the translator had stopped translating what I was saying. He was waiting for the chairman to finish speaking.

'You are fortunate that this is a country founded on mercy and a respect for human rights,' he was saying. 'After the Great Patriotic War, in which so many innocent Soviet citizens died, it was the wish of Comrade Stalin that the death penalty should be abolished in our country. Consequently, the capital punishment handed down to you is commuted to twenty-five years' hard labour.'

Stunned at my declared fate, I was led out of the court to a yard outside where a Black Maria was waiting for me, its engine running. The driver already had my details, which seemed to indicate that the court's verdict had been a foregone conclusion. The Black Maria was divided into four little cells, each of them so cramped and low you had to bend over double just to get inside one. The metal door was perforated with little holes like the mouthpiece of a telephone. They were considerate like that, the Ivans. We set off at speed – you might have thought the driver was in charge of a getaway car after a bank robbery – and when we stopped, we stopped very suddenly, as if the police had forced us to stop. I heard more prisoners being loaded into the Black Maria and then we were off, again at high speed, with the driver laughing loudly as we skidded around one corner and then another. Finally we stopped, the engine was switched off, the doors were flung open and all was made plain. We were beside a train that was already under steam and making strong exhalated hints that it was impatient to leave, but to where, no one said. Everyone in the Black Maria was ordered to climb aboard a cattle car alongside several other Germans whose faces looked as grim as I was feeling. Twenty-five years! If I lived that long it was going to be 1970 before I went home again! The door of the cattle car slid shut with a bang, leaving, us all in partial darkness; the bogies shifted a little, throwing us all into each other's arms, and then the train set off.

'Any idea where we're going?' said a voice.

'Does it matter?' said someone. 'Hell's the same whichever fiery pit you're in.'

'This place is too cold to be Hell,' said another.

I peered through an air hole in the wall of the cattle car. It was impossible to see where the sun was. The sky was a blank sheet of grey that was soon black with night and salted with snow. At the other end of the wagon a man was crying. The sound was tearing us all apart.

'Someone say something to that fellow, for God's sake,' I muttered loudly.

'Like what?' said the man next to me.

'I dunno, but I'd rather not listen to that sound unless I have to.'

'Hey, Fritz,' said a voice. 'Stop that crying, will you? You're spoiling the party for some fellow at the other end of the carriage. This is supposed to be a picnic, see? Not a funeral cortege.'

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Field Grey»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Field Grey» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Field Grey» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.