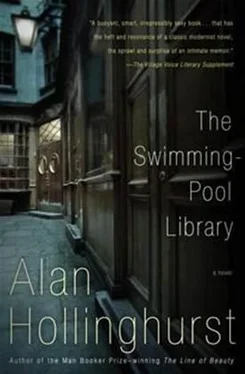

Alan Hollinghurst - The Swimming-Pool Library

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Alan Hollinghurst - The Swimming-Pool Library» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Жанр: Триллер, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:The Swimming-Pool Library

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Swimming-Pool Library: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The Swimming-Pool Library»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

The Swimming-Pool Library — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The Swimming-Pool Library», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

Bill turned to me with a look of relief. ‘He’s done it,’ he said. ‘They’ll have to stop it now. Yes, he’s done it.’ The shouts in the hall were modified with a sympathy easily accorded to the loser, and Alastair, himself looking rather stunned, cheated somehow by his own victory, jogged about in the ring, punching the air, which was all that was left for him, and showing he had hardly noticed, he needed a fight. After brief deliberations between the ref and the officious, serious judges (this was their life, after all) the unanimous decision was announced. Then Alastair relaxed, hugged and patted his opponent with a careless fondness, and did his lively round of thanks and handshakes. I was moved by the propriety of this.

Bill of course went off with his champion, and after I’d watched the opening of the next fight, which didn’t promise to go so well for Limehouse, I wondered what the hell I was doing and sloped off too through the audience and out by the swinging blue doors. Through another door on the right I heard the familiar fizz of showers and felt the familiar need to see what was going on in them.

There was such an innocence to the place that they saw nothing suspicious in my presence there-nothing either in Bill’s, who, freed from adult prerogatives, absorbed himself with earnest complicity in this little manly world. The mood here also was one of pure sportsmanship, of candid bustle, like a chorus dressing room. Both teams shared the facilities, and Alastair and his opponent sat side by side on a bench, Alastair undoing, with patient, soldierly tenderness, the bandages that bound the black boy’s hands, and then offering his own hands to be undone, his wrists lying intimately on the other’s hairless thigh. The black boy wore a plaster woefully along his already puffing cheekbone.

‘I’d have a shower, lads,’ said Bill professionally. Watching the lads undress I felt, as perhaps Bill always felt too, not only randy curiosity but a real pang of exclusion, in every way outside their world. The shower was a perfunctory business and soon Alastair was back by us, towelling himself with surprising unselfconsciousness for a sixteen-year-old. I realised why it was, when, after tucking his long-skinned dick into cheap red knickers, and pulling on a grey jersey and those baggy, splotch-bleached jeans which look as though a circle of kids have jacked off all over them, he said to Bill: ‘I got to go and see my girlfriend.’

Bill grinned at him wretchedly. ‘Don’t do anything I wouldn’t do,’ he said.

7

At my prep school the prefects (for some errant Wykehamical reason) were called Librarians. The appellation seemed to imply that in the care of books lay the roots of leadership-though, by and large, there was nothing bookish about the Librarians themselves. They were chosen on grounds of aptitude for particular tasks, and were known officially by the name of their responsibility. So there were the Chapel Librarian, the Hall Librarian, the Garden Librarian and even, more charmingly, the Running and the Cricket Librarians. My aptitude, from the tropically early onslaught of puberty forwards, had been so narrowly, though abundantly, for playing with myself and others, that it was only in my last term, as a shooting, tumid thirteen-year-old, that I achieved official status, and was appointed Swimming-Pool Librarian. My parents were evidently relieved that I was not entirely lost (urged absurdly to read Trollope I had stuck fast on Rider Haggard) and my father, in a letter to me, made one of his rare witticisms: ‘Delighted to hear that you’re to be Swimming-Pool Librarian. You must tell me what sort of books they have in the Swimming-Pool Library.’

I was an ideal appointment, not only a good swimmer but one who took a keen interest in the pool. A quarter of a mile from the school buildings, down a chestnut-lined drive, the small open-air bath and its whitewashed, skylit changing-room saw all my earliest excesses. On high summer nights when it was light enough at midnight to read outside, three or four of us would slip away from the dorms and go with an exaggerated refinement of stealth to the pool. In the changing-room serious, hot No 6 were smoked, and soap, lathered in the cold, starlit water, eased the violence of cocks up young bums. Fox-eyed, silent but for our breathing and the thrilling, gross little rhythms of sex-which made us gulp and grope for more-we learnt our stuff. Then, noisier, enjoining each other to silence, we slid into the pool and swam through the underwater blackness where the cleaning device, humming faintly, swung round the sucking tentacle of its hose. On the dorm floor in the morning there were often dead leaves, or grassy lumps of mud, which we had brought in on our shoes in the small hours and which seemed mementoes of some Panic visitor.

I told Phil all or some of this when he asked me about swimming, and showed him my Swimming-Pool Librarian badge (brass letters on red enamel, with a bendy brass pin) which, along with my preliminary lifesaving badge, I still had and kept in a round leather stud-box on my dressing-table. The box itself, aptly enough, was a gift from Johnny Carver, my great buddy and love at Winchester. Phil was round at my place for the first time, and it seemed to arouse a curiosity in him which had been almost abnormally absent before.

‘It smells so rich,’ he said.

‘That onion flan, yesterday-my old socks…’ I apologised.

He was close enough to me now to laugh at anything. ‘No, no. I mean it smells expensive. Like a country house.’

I still dream, once a month or so, of that changing-room, its slatted floor and benches. In our retrogressive slang it was known as the Swimming-Pool Library and then simply as the Library, a notion fitting to the double lives we led. ‘I shall be in the library,’ I would announce, a prodigy of study. Sometimes I think that shadowy, doorless little shelter-which is all it was really, an empty, empty place-is where at heart I want to be. Beyond it was a wire fence and then a sloping, moonlit field of grass-‘the Wilderness’-that whispered and sighed in the night breeze. Nipping into that library of uncatalogued pleasure was to step into the dark and halt. Then held breath was released, a cigarette glowed, its smoke was smelled, the substantial blackness moved, glimmered and touched. Friendly hands felt for the flies. There was never, or rarely, any kissing-no cloying, adult impurity in the lubricious innocence of what we did.

‘Are you into kids?’ Phil asked.

‘I’m into you, darling.’

‘Yeah, but…’

‘You know it’s illegal, our affair. Officially, I can’t touch you for another three years.’

‘Christ,’ he said, as if that altered everything, and paced around the room. ‘No, I think kids can be quite something. After fourteen or so. I mean I wouldn’t touch them when they were really small …’

‘No-but a little chap who’s already got a big donger on him gets a hard-on all the time, doesn’t know what to do with this thing that’s taking over his life-that’s quite something, as you say.’

Phil grinned and blushed. One of the reasons he loved me was that I put these things into words, legitimised them just as I was most risqué. He was encouraged by this franc-parler to explore the new possibilities of talk, sometimes in so reckless a way that I thought he must be making things up. The men at the Corry came in for particular attention. ‘I really dig that Pete/Alan/Nigel/Guy’, he would quietly celebrate as we dressed after a shower, or emerged onto the evening streets again. The wonderfully handsome, virile and heterosexual Maurice seemed to excite him in particular. ‘What a pity he’s straight , man,’ Phil would say, with charming and earnest shakings of the head.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The Swimming-Pool Library»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The Swimming-Pool Library» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The Swimming-Pool Library» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.