In a moment we heard footsteps in the passage and the sound of Mr Carswall's voice raised in triumph: "And he did not know I had the last heart, the poor fool, he thought Lady Ruispidge had it. No, it was neatly done, by God, and after that trick, the rubber was ours."

The door flew open, colliding with the back of a chair. In an instant the quiet parlour had filled to overflowing with lights, noise, people. As well as Mr Carswall, there was Miss Carswall, Mrs Lee, Sir George and the Captain. Lady Ruispidge had retired for the night but her sons had insisted on escorting Mr Carswall's party back to Fendall House.

Mr Carswall was not drunk, merely boisterous. In Mrs Johnson's absence, Lady Ruispidge had condescended to partner him and I believe he felt he had acquitted himself well, both at whist and in society in general. Mrs Lee and a clergyman had opposed them in the card room, and Mrs Lee did her best to appear complacent about the losses she had sustained.

Miss Carswall, we soon learned, had danced almost every dance, many of them with Sir George, two with the Captain, and several with officers from the local militia. She looked very handsome, with her colour high and the excitement running through her like electricity. Sir George had taken her down to supper, and everyone had been most attentive.

Sir George was quieter, but almost equally pleased with himself. His brother, on the other hand, was at pains to give the impression that he had been miserable for most of the time: first, contemplating how Mrs Frant was faring on her own, and later, when the news of Mrs Johnson's indisposition had reached him, being sensible of Mrs Frant's kindness to his unfortunate cousin. Indeed, to hear him speak, one would think that Mrs Frant, but for an accident of faith, were a prime candidate for canonisation. No one seemed unduly concerned about Mrs Johnson – Sir George remarked that hers was one of those unequal constitutions that alternate between spells of intense activity and periods of low spirits and general debility. He trusted that his cousin's indisposition would not inconvenience us in any way. A good night's sleep would soon set her right.

"She certainly sleeps soundly," cried Mr Carswall. "Why, I heard her snoring as we passed her door."

The hour was late – after one o'clock in the morning – and, having escorted the Carswalls back to their apartment and made civil inquiries after the well-being of Mrs Frant and Mrs Johnson, the Ruispidge brothers had no further excuse for remaining. Almost immediately after their departure, there occurred an ugly little scene which made me wonder whether Carswall were drunker than he appeared.

Mrs Frant rose, saying she was fatigued and would retire. I was about to open the door for her when Carswall plunged across the room and forestalled me. As she passed him in the doorway, he laid a hand like a great paw on her arm and begged the favour of a goodnight kiss.

"After all," said he, "are we not cousins? Should not cousins love each other?" The intonation he gave the words made it quite clear what sort of love he had in mind.

"Oh, Papa," cried Miss Carswall. "Pray let Sophie pass; she is quite fagged."

The sound of his daughter's voice rather than the words distracted him for an instant. Mrs Frant slipped into the passage. I heard her talking to Miss Carswall's maid. Then came the sound of a door opening and closing.

"Eh?" Mr Carswall said to no one in particular. "Fagged? Aye, no wonder – look at the time." He thrust his fingers into his waistcoat pocket and in a moment was matching his actions to his words. Then he turned his back to us and went to stand at the window. "God damn it, it is still snowing."

He wished us a curt goodnight and stamped out of the room, jingling the change in his pocket. The rest of us followed almost at once. Miss Carswall lingered in the passage, however, adjusting the wick of her candle. Mrs Lee went on ahead and into her own chamber. Miss Carswall turned back to me.

"I am sorry you was not at the ball," she said. "It was but a country assembly, of course, full of tradesmen and farmers' wives, but it was most agreeable for all that." She lowered her voice. "And it would have been more agreeable, had you been there."

I bowed, looking at her; and I could not help admiring what I saw.

Miss Carswall studied my face for an instant. Then she took up her candle and turned as if about to retire. But she checked herself. "Would you do something for me, sir?"

"Of course."

"I have a mind to perform an experiment. When you go to your room, will you stand at the window for a moment or two, and look out?"

"If you wish. May I ask why?"

"No, sir, you may not." She devastated me with a smile. "That would be quite unscientific – it would ruin my experiment. We natural philosophers would pay any price to avoid that."

A moment later I was alone. I threaded my way through passages and up and down the stairs until I reached my room. The old building was full of noises, and I encountered several servants going about their business.

At length I climbed the last flight of stairs to my door. My room felt almost as cold as the ice-house at Monkshill-park. My body was tired but my mind was restless, stirred by the events of the evening. I threw on my greatcoat and felt in my valise for a paper of cigars. I forced open one half of the casement window which had been wedged with newspaper. A moment later I was leaning on the sill and filling my lungs with sweet, soothing smoke.

The roofs of the city were silver and white. Somewhere a church clock sounded the half-hour and was answered by others across the city, their bells muted by the covering of snow. My mind filled with a parade of images, its constituent parts as random as the flakes still falling from the sky.

I saw Miss Carswall, of course, with that smile that promised so much, and Mrs Frant's gravely beautiful face lit by a guttering candle flame and the glow of the parlour fire. I saw Mrs Johnson huddled on the pavement, and a man running across the road from her. I looked further back, to the man glimpsed at the window of Grange Cottage, to the dried, yellowing finger I had found in the satchel, to the mutilated corpse on the trestle at Wellington-terrace.

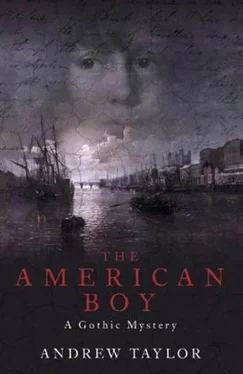

Dansey, too, and Rowsell joined the parade, and I wondered idly at the reasons for the kindnesses they showed me. (One of the oddest things about affection is surely that in many cases its object so little deserves it.) I thought of the boys, Charlie and Edgar, so like each other in appearance with their high foreheads, their air of refinement, their vulnerability, but so different in their temperaments. I had met the American boy on my first visit to Stoke Newington, the day I had first seen Sophia Frant, and he seemed, albeit unconsciously, to have acted as the proximate cause of much that had happened. He had brought David Poe into my life, and without David Poe I would not have become entangled with the Carswalls and the Frants.

I was also aware of an underlying layer of anxiety in my mind, which reminded me of something. After another half-inch of the cigar, I had fixed the memory like a butterfly with a pin: I had felt this way in the days before Waterloo: then, as now, there had been a sense of foreboding, of disaster drawing ineluctably closer. The difference was this: then I had known the nature of the impending catastrophe; now I did not.

Ayez peur, I thought. Ayez peur. Perhaps the quack's parrot was wiser than it knew.

All at once, my mind was jolted away from these aimless but gloomy reflections. A long narrow triangle of yellow light appeared in the wall of the house's modern wing beyond the shrubbery, almost opposite my window but several feet lower. The heavy curtains were moving. The triangle of light widened still further and a figure carrying a candle slipped through the gap into the narrow space between curtains and glass. The left hand cupped the flame and concealed its owner's identity. All of a sudden, the window embrasure was neither one thing nor the other, as equivocal as a proscenium. It seemed to me as though I were in a box overlooking the pit of a darkened theatre.

Читать дальше

Конец ознакомительного отрывка

Купить книгу