* * *

CHEL’S ONLY MEMORY from her childhood in Kiaqix was of riding on her father’s shoulders. It was early evening in the dry season, and Alvar had finished working for the day, so he took her to settle a claim with a neighbor over a chicken missing from their coop. From her perch, Chel watched as young girls brought pails of cornmeal from the mill back to their mothers, to be used for dinner tortillas and breakfast drinks. Whistle music came from the houses, and a drum was played; Alvar danced to it as he walked, and Chel felt the sandpaper of his beard on her legs.

She’d been back to her homeland several times since her mother took her from Kiaqix, and each time she fell more in love with the communal bonfires where stories of the ancestors were still told, the labor-sharing on the milpas at harvest time, the gifts from the beekeepers, and the villagers’ spirited volleyball and soccer games.

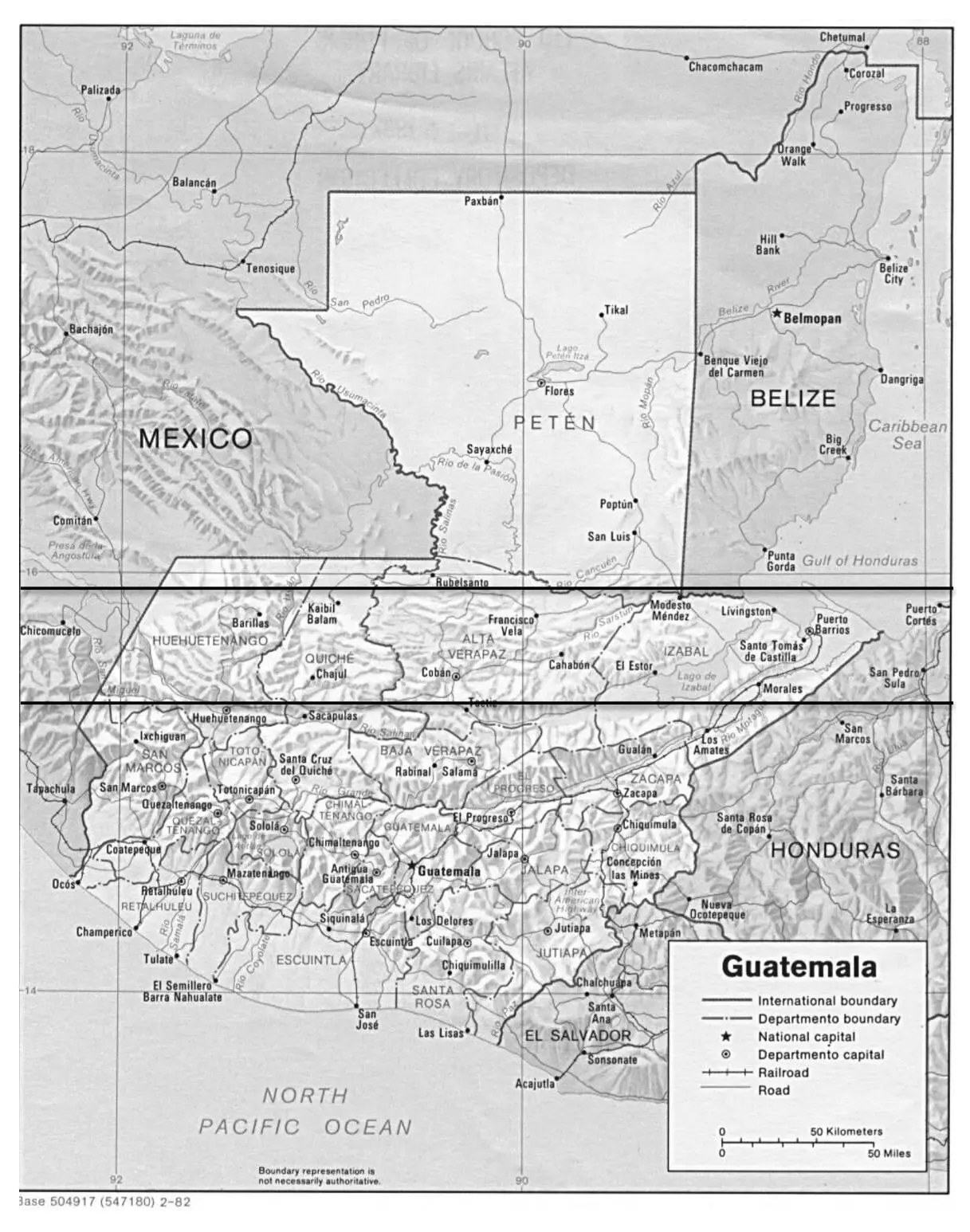

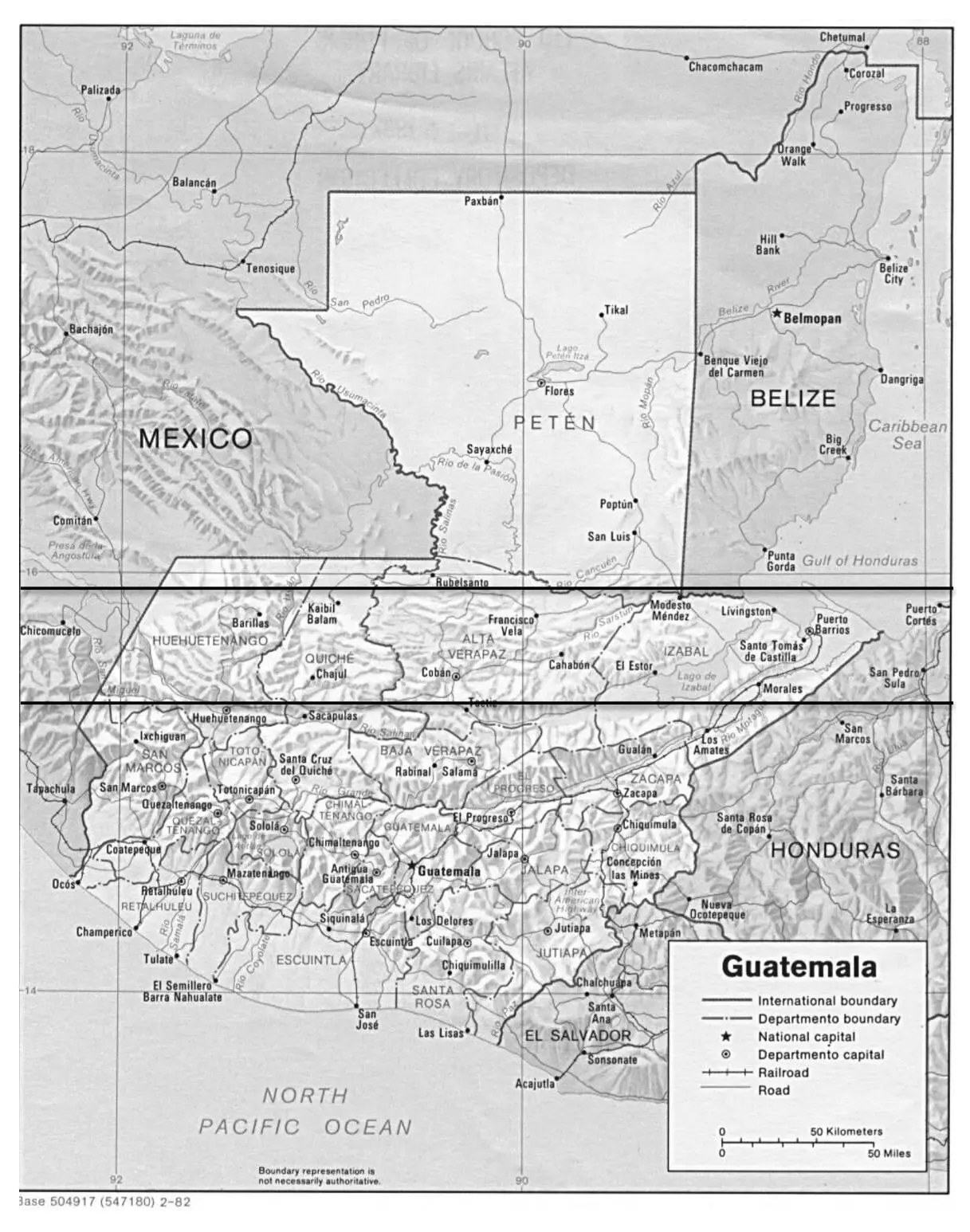

Kiaqix was hundreds of miles from any of the big cities, the highways, or the ruins, and reaching it wasn’t easy. You could take a small plane to a landing strip five miles east. But there was only one car in the village of two thousand people, so you’d likely be going those last five miles on foot. Factor in the rainy season, which made the one road into town treacherous, and you were dealing with one complicated journey.

More, Chel’s mother refused to return to Guatemala and always begged Chel not to either. Ha’ana believed that as long as the ladinos controlled the country, the Manu family would never be safe. With tensions high and violence erupting again, Ha’ana’s anxiety had only increased.

“What is it?” Patrick asked from the doorway. Behind him, the planetarium was pitch-dark, as if the world ended here, in this tiny office.

She showed him the map she’d pulled up online.

He leaned over her to better see the screen, and instinctively Chel put her hand on the cuff of his shirt, feeling the fabric at her fingertips. Whatever was lost between them, the feel of him was so familiar. “Are there any major ruins on that latitude?” he asked.

Chel shook her head.

“But Kiaqix is a small village,” Patrick said. “You said the scribe is talking about a city of tens of thousands.”

He was right: Kiaqix was a no-man’s-land for the ancients. No artifacts had been discovered there from the classic era, and the nearest ruins were two hundred miles away.

Then again, Chel thought, staring at the map, the circumstances described in the codex were eerily similar to the stories she knew: the oral history of a king destroying his own city. “The Original Trio,” she reminded Patrick. “Kiaqix was supposedly founded when three city-dwellers escaped to the jungle.”

“I thought you didn’t believe there was a lost city. That it was a legend.”

“There’s no evidence either way,” Chel whispered. “All we have are the oral history and the people who say they saw the ruins but couldn’t prove it.”

Remembering now, Patrick said, “Your uncle, right?”

“My father’s cousin.”

More than three decades ago, Chiam Manu left Kiaqix and went into the jungle for more than a week. When he returned, he claimed to have found Kiaqix’s lost city, from which the oral history claimed their ancestors came. But Chiam brought nothing back and would tell no one in which direction the lost city lay. Few believed him; most ridiculed Chiam and called him a liar. When he was murdered by the army weeks later, the truth died with him.

“What about Volcy?” Patrick continued. “You think it’s possible he’s from Kiaqix?”

Chel took a breath. “Everything he said about his village could be said of Kiaqix, I guess. And also about three hundred other villages across the Petén.”

Patrick put his hand on top of hers and leaned closer. Chel smelled traces of the sandalwood soap he always used. “How does this book land in your lap in the middle of all this? It’s one hell of a coincidence, don’t you think?”

Chel turned back to the computer screen. There was no word in Qu’iche for coincidence , and it wasn’t only a problem of translation. When events happened together and pointed in a single direction, her people used a different word. It was the same word Chel’s father used in his final letter from prison, when he sensed his death was near: ch’umilal.

Fate.

12.19.19.17.14

DECEMBER 15, 2012

JUST AFTER SIX A.M., WHILE DAVIES AND THANE REVIEWED every detail of their plan for a final time, Stanton stepped out onto the empty boardwalk to join a conference call with government officials in L.A., Atlanta, D.C., and around the country. The sun was inching toward the coastline and hadn’t started cooking the ocean air, so in his thin, long-sleeved shirt and jeans, he was underdressed for the chill lingering on the Walk. The only sound competing with the lapping of the waves was an invisible helicopter churning somewhere in the distance.

Tuning out a procedural roll call, Stanton glimpsed a small circle of men sitting in sun chairs right near the shore, all wearing eye shields. At first he couldn’t imagine who was brazen enough to meet right now in violation of the curfew. Then Stanton realized they were sitting in exactly the same spot as the Venice Beach men’s AA meeting always did. They often congregated at dawn, and, however surprising, it was a strange comfort to Stanton to know that some appointments couldn’t be missed.

“The utilities can’t keep up with the demands or the outages,” a FEMA deputy was saying on the phone now. “No electricity means no potable water.”

Los Angeles had been on the brink of an energy crisis for decades. Now, with half of the city suffering from anxiety-related sleeplessness, lights and televisions and computers ran twenty-four hours a day. Blackouts spread. Water consumption had skyrocketed. Taps could run dry within a week.

“What are we doing about bodies?” Stanton broke in, out of turn. “Houses across the city could have decaying corpses inside them.”

“We have to take them to a central location,” somebody replied. He didn’t recognize the voice—there were so many bureaucrats involved in every decision now.

“We could be talking about thousands in a few days,” Stanton said. There were more than eight thousand known victims of VFI citywide. “You don’t have the equipment for that kind of biohazard, and there’d be no way to ensure the safety of the workers.”

“Well, we have to do something,” Cavanagh cut in, “and I can’t believe I’m saying this, but I’m starting to think that means telling people they have to douse the bodies with acid or lye and let them dissolve in bathtubs.”

Stanton’s boss was taking the call from the recession-shuttered post office in East L.A. that had been turned into a CDC command center. From the tone of Cavanagh’s voice, Stanton could feel the toll all this was exacting on her. Already, forty-two CDC investigators and nurses were infected with VFI, and he knew Cavanagh well enough to know that she blamed herself. She’d personally selected many of them to come out from Atlanta to help manage the outbreak.

As the call broke up, Stanton sensed an opening and asked his boss to stay on the line. One way or another, he, Davies, and Thane were going to test the antibodies in the next twenty-four hours. Their plans were in place. But if he could convince Cavanagh that it was the right thing, they’d have access to a much larger sample group and they’d be acting within the law.

Читать дальше