Dustin Thomason

12.21

A Novel

To my sister, Heather, who helps me understand

that blood really is thicker,

and to Janet, the best mother in the world,

our very own giving tree.

HE STANDS SILENTLY IN THE MOONLIGHT AGAINST THE WALL OF the temple, the small bundle held tightly under his arm. The sisal wrapping chafes against his skin, but he welcomes the feeling. It reassures him. In this drought-stricken city, he would not trade this package, even for water. The ground beneath his sandals is cracked and dry. The green world of his childhood is gone, and he is beginning to wonder if soon he will be too.

Satisfied that the temple guards haven’t detected his presence, he hurries toward the central square, where artisans and tattoo-painters once thrived. Now it is populated only by beggars, and beggars, when hungry, can be dangerous. But tonight he is lucky. There are only two men standing by the east temple. They have seen him before, and they know he gives to them what he can. Still, he holds the bundle close as he goes.

At the boundary between the central square and the maize silos, there is a guard posted. No more than a boy. For a moment, he considers burying the bundle and returning for it later, but the earth is dust, and the winds drive through fields where trees once stood. Nothing in this parched city remains buried for long.

He takes a breath and continues walking forward.

“Royal and Holy One,” calls the boy. “Where are you going?” The boy’s eyes are tired, hungry, but spark when they take in the bundle under the man’s arm.

“To my fasting cave.”

“What are you carrying?”

“Incense for my dedications.”

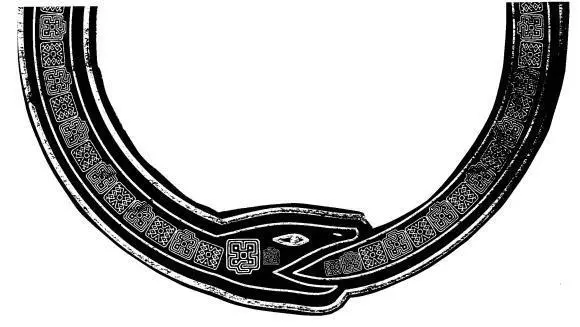

The man tightens his arm around the parcel and prays silently to Itzamnaaj .

“But there has been no incense at the market for days, Royal and Holy One.” The guard’s voice is jaded. As if all men lie now to survive. As if all innocence has fled with the rains. “Give it to me.”

“Warrior, you are right. It is not incense but a gift for the king.” He has no choice but to invoke the king’s name, though the king would have his heart ripped out if he knew what he was carrying.

“Give it to me,” the boy says again.

The man reluctantly obeys.

The boy’s fingers unwrap the bundle roughly, but when the sisal falls away, he sees disappointment in the young guard’s eyes. What had he been hoping for? Maize? Cacao? He does not understand what he has seen. Like most boys in these times, he understands only hunger.

Rewrapping it quickly, the man hurries away from the guard, offering thanks to the gods for his good fortune. His small cave lies at the eastern edge of the city, and he slips through the opening undetected.

There are cloths spread across the floor, placed here in preparation for this moment. He lights his candle, sets the bundle at a careful distance from the wax, then carefully wipes his hands. He drops to his knees and reaches for the sisal. Inside is a folded stack of pages made from the bark of a fig tree, hardened with a glaze of limestone paste.

With the great but seemingly effortless care of a man who has trained for this act his entire life, he unfolds the paper. Twenty-five times it has been doubled back on itself, and when it is completely unfurled, the blank pages stretch across the width of the cave.

From behind his hearth, he gathers three small bowls of paint. He has scraped cooking pots to make black ink, shaved rust from the rocks to make red, and searched fields and riverbeds for anil and clay to make indigo. Finally, he makes a puncture in the skin of his arm. He watches the crimson rivulets run over his wrist and into the bowls of paint before him, sanctifying the ink with his blood.

Then he begins to write.

12.19.19.17.10

DECEMBER 11, 2012

DR. GABRIEL STANTON’S CONDO SAT AT THE END OF THE BOARD-WALK, before the Venice Beach footpath morphed into lush lawns where the tai chi lovers gathered. The modest duplex wasn’t entirely to Stanton’s taste. He would have preferred something with more history. But on this odd stretch of the California coastline, the only options to choose between were run-down shacks and contemporary stone and glass. Stanton left his home just after seven a.m. on his old Gary Fisher bike and headed south with Dogma, his yellow Labrador, running beside him. Groundwork, the best coffee in L.A., was only six blocks away, and there Jillian would have a triple shot of Black Gold ready for him the minute he walked in.

Dogma loved the mornings as much as his owner did. But the dog wasn’t allowed into Groundwork, so after Stanton tied him up, he made his way inside alone, waved at Jillian, collected his cup, and checked out the scene. A lot of the early clientele were surfers, their wetsuits still dripping. Stanton was usually up by six, but these guys had been up for hours.

Sitting at his usual table was one of the boardwalk’s best-known and strangest-looking residents. His entire face and shaved head were covered with intricate designs, as well as rings, studs, and small chains protruding from his earlobes, nose, and lips. Stanton often wondered where a man like Monster came from. What had happened to him in early life that led to the decision to cover his body entirely with art? For some reason, whenever Stanton imagined Monster’s origins, he saw a split-level home near a military base—exactly the type of houses in which he himself had spent his childhood.

“How’s the world out there doing?” Stanton asked.

Monster looked up from his computer. He was an obsessive news junkie, and when he wasn’t working at his tattoo shop or entertaining tourists as part of the Venice Beach Freak Show, he was here posting comments on political blogs.

“Other than there being only two weeks before the galactic alignment makes the magnetic poles reverse and we all die?” he asked.

“Other than that.”

“Hell of a nice day out there.”

“How’s your lady?”

“Electrifying, thanks.”

Stanton headed for the door. “If we’re still here, I’ll see you tomorrow, Monster.”

After Stanton downed his Black Gold outside, he and Dogma continued south. A century ago, miles of canals snaked through the streets of Venice, tobacco magnate Abbot Kinney’s re-creation of the famed Italian city. Now virtually all of the waterways where gondoliers once ferried residents were paved over and covered with steroid-fueled gyms, greasy-food stands, and novelty T-shirt shops.

Stanton had ruefully watched a rash of “Mayan apocalypse” graffiti and trinkets pop up all over Venice in recent weeks, vendors taking advantage of all the hype. He’d been raised Catholic but hadn’t been in a church in years. If people wanted to seek their destiny or believe in some ancient clock, they could go right ahead; he’d stick to testable hypotheses and the scientific method.

Fortunately, it seemed not everyone in Venice believed December 21 would bring the end of the world; red and green lights also decorated the boardwalk too, just in case the crackpots had it wrong. Yuletide was a strange time in L.A. Few transplants understood how to celebrate the holidays at seventy degrees, but Stanton loved the contrast—Santa hats on rollerbladers, suntan lotion in stockings, surfboards festooned with antlers. A ride along the beach on Christmas was as spiritual as he got these days.

Читать дальше