Suffering from severe asthma by age six, she had been treated with a high dose of a promising new drug — the first of the world’s glucocorticoids, or steroid hormones — which had cured her asthma symptoms in miraculous fashion. Sadly, the drug’s unanticipated side effects had not emerged until years later when Sinskey passed through puberty … and yet never developed a menstrual cycle. She would never forget the dark moment in the doctor’s office, at nineteen, when she learned that the damage to her reproductive system was permanent.

Elizabeth Sinskey could never have children.

Time will heal the emptiness , her doctor assured, but the sadness and anger only grew inside her. Cruelly, the drugs that had robbed her of her ability to conceive a child had failed to rob her of her animal instincts to do so. For decades, she had battled her cravings to fulfill this impossible desire. Even now, at sixty-one years old, she still felt a pang of hollowness every time she saw a mother and infant.

“It’s just ahead, Dr. Sinskey,” the limo driver announced.

Elizabeth ran a quick brush through her long silver ringlets and checked her face in the mirror. Before she knew it, the car had stopped, and the driver was helping her out onto the sidewalk in an affluent section of Manhattan.

“I’ll wait here for you,” the driver said. “We can go straight to the airport when you’re ready.”

The New York headquarters of the Council on Foreign Relations was an unobtrusive neoclassical building on the corner of Park and Sixty-eighth that had once been the home of a Standard Oil tycoon. Its exterior blended seamlessly with the elegant landscape surrounding it, offering no hint of its unique purpose.

“Dr. Sinskey,” a portly female receptionist greeted her. “This way, please. He’s expecting you.”

Okay, but who is he? She followed the receptionist down a luxurious corridor to a closed door, on which the woman gave a quick knock before opening it and motioning for Elizabeth to enter.

She went in, and the door closed behind her.

The small, dark conference room was illuminated only by the glow of a video screen. In front of the screen, a very tall and lanky silhouette faced her. Though she couldn’t make out his face, she sensed power here.

“Dr. Sinskey,” the man’s sharp voice declared. “Thank you for joining me.” The man’s tautly precise accent suggested Elizabeth’s homeland of Switzerland, or perhaps Germany.

“Please sit,” he said, motioning to a chair near the front of the room.

No introductions? Elizabeth sat. The bizarre image being projected on the video screen did nothing to calm her nerves. What in the world?

“I was at your presentation this morning,” declared the silhouette. “I came a long distance to hear you speak. An impressive performance.”

“Thank you,” she replied.

“Might I also say you are much more beautiful than I imagined … despite your age and your myopic view of world health.”

Elizabeth felt her jaw drop. The comment was offensive in all kinds of ways. “Excuse me?” she demanded, peering into the darkness. “Who are you? And why have you called me here?”

“Pardon my failed attempt at humor,” the lanky shadow replied. “The image on the screen will explain why you’re here.”

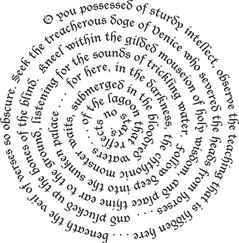

Sinskey eyed the horrific visual — a painting depicting a vast sea of humanity, throngs of sickly people, all climbing over one another in a dense tangle of naked bodies.

“The great artist Doré,” the man announced. “His spectacularly grim interpretation of Dante Alighieri’s vision of hell. I hope it looks comfortable to you … because that’s where we’re headed.” He paused, drifting slowly toward her. “And let me tell you why.”

He kept moving toward her, seeming to grow taller with every step. “If I were to take this piece of paper and tear it in two …” He paused at a table, picked up a sheet of paper, and ripped it loudly in half. “And then if I were to place the two halves on top of each other …” He stacked the two halves. “And then if I were to repeat the process …” He again tore the papers, stacking them. “I produce a stack of paper that is now four times the thickness of the original, correct?” His eyes seemed to smolder in the darkness of the room.

Elizabeth did not appreciate his condescending tone and aggressive posture. She said nothing.

“Hypothetically speaking,” he continued, moving closer still, “if the original sheet of paper is a mere one-tenth of a millimeter thick, and I were to repeat this process … say, fifty times … do you know how tall this stack would be?”

Elizabeth bristled. “I do,” she replied with more hostility than she intended. “It would be one-tenth of a millimeter times two to the fiftieth power. It’s called geometric progression. Might I ask what I’m doing here?”

The man smirked and gave an impressed nod. “Yes, and can you guess what that actual value might look like? One-tenth of a millimeter times two to the fiftieth power? Do you know how tall our stack of paper has become?” He paused only an instant. “Our stack of paper, after only fifty doublings, now reaches almost all the way … to the sun.”

Elizabeth was not surprised. The staggering power of geometric growth was something she dealt with all the time in her work. Circles of contamination … replication of infected cells … death-toll estimates. “I apologize if I seem naive,” she said, making no effort to hide her annoyance. “But I’m missing your point.”

“My point?” He chuckled quietly. “My point is that the history of our human population growth is even more dramatic. The earth’s population, like our stack of paper, had very meager beginnings … but alarming potential.”

He was pacing again. “Consider this. It took the earth’s population thousands of years — from the early dawn of man all the way to the early 1800s — to reach one billion people. Then, astoundingly, it took only about a hundred years to double the population to two billion in the 1920s. After that, it took a mere fifty years for the population to double again to four billion in the 1970s. As you can imagine, we’re well on track to reach eight billion very soon. Just today, the human race added another quarter-million people to planet Earth. A quarter million . And this happens every day — rain or shine. Currently, every year, we’re adding the equivalent of the entire country of Germany.”

The tall man stopped short, hovering over Elizabeth. “How old are you?”

Another offensive question, although as the head of the WHO, she was accustomed to handling antagonism with diplomacy. “Sixty-one.”

“Did you know that if you live another nineteen years, until the age of eighty, you will witness the population triple in your lifetime. One lifetime — a tripling . Think of the implications. As you know, your World Health Organization has again increased its forecasts, predicting there will be some nine billion people on earth before the midpoint of this century. Animal species are going extinct at a precipitously accelerated rate. The demand for dwindling natural resources is skyrocketing. Clean water is harder and harder to come by. By any biological gauge, our species has exceeded our sustainable numbers. And in the face of this disaster, the World Health Organization — the gatekeeper of the planet’s health — is investing in things like curing diabetes, filling blood banks, battling cancer.” He paused, staring directly at her. “And so I brought you here to ask you directly why the hell the World Health Organization does not have the guts to deal with this issue head-on?”

Читать дальше

Конец ознакомительного отрывка

Купить книгу