“That’s the airport talking.”

“Could be.”

“Well, it’s all for me, honey. Don’t try to sidestep it. Feel it.”

“I do feel it.”

“Soon you’ll be back home in our apartment and you’ll feel cozy again,” said Naomi.

Nathan began to feel the eyes of his loungemates flicking up at him. Why would they be listening? “I’m not going right back to NYC. I’ve been diverted to Toronto. You know, Canada.”

Under her covers, Naomi felt a twinge of… could it be separation anxiety? Her nest wasn’t busy enough. She slid out of bed and began to gather electronic devices, dumping them on the duvet as she found them. “But you’re not in the air yet. How can they divert you?”

“I diverted myself. I’ll email you the address and stuff.”

Naomi jumped back under the covers again, the nest reconstructed, ramparts, moats, drawbridges. “What’s going on? Toronto? What, Sunnybrook Hospital?”

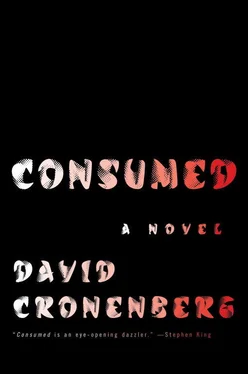

Nathan’s voice went sotto. Paranoia thickened in his brain like Alzheimer’s plaque, as it always did when he got that shiver of a great idea for a piece. “You remember Roiphe’s disease?”

“Oh, sure. The thing that killed Wayne Pardeau. But they cracked it, didn’t they? Extincted it. Only samples left in stainless-steel containers. After that, pas grand-chose , as I recall.”

“In itself, as diseases go, ultimately, pas grand-chose , no. But extinct, also no.”

“You have a brilliant angle on it?”

Nathan’s sharp, involuntary intake of breath went unremarked. “Let’s say compelling. I have a compelling angle on it.”

By now Naomi was on the same pages Nathan had been on—with the Air, not the old MacBook Pro for the moment—and she was looking at Roiphe’s house in Toronto in Google Street View. A freshly built faux chateau, Victorian kitsch pastiche of the worst kind. Oh, well. What did you expect? An old Canadian Jewish doctor with some money. But nice leafy street. “Roiphe’s there, isn’t he? In Toronto. You’re going to see him.”

Nathan had heard the rustle of Naomi’s keyboard, but out of his inexpressible guilt he wanted to compliment her. “Hey, that’s pretty good for somebody who doesn’t do medical. Try this. Do you know Roiphe’s first name?”

“Are we playing Faster Fingers or are we thinking?” Faster Fingers was their code for supplanting brain/memory with Google Search.

“Too late for the first-name thing, I guess.”

“I’m looking at Barry’s face right now,” said Naomi. “Rabbinical Jimmy Stewart, somehow. Holy Blossom Temple or something in my Toronto past. Do you know Alzheimer’s first name? No fingers.”

“Sure: Aloïs. But did you know that Alzheimer’s assistant turns out to be Creutzfeldt of Creutzfeldt-Jakob’s? You know, human mad cow disease? Sort of ?”

“I forgot what you do.”

Nathan, starting to cook now—and it was in articulating things to Naomi that the cooking really happened, part of their closeness, though he worried it didn’t really work in the opposite direction—edged himself down lower into the lounge’s carpeting, bringing the phone closer to floor level. He didn’t want his lips read. “What happens if this guy, Barry Roiphe, the guy the disease was named after, what if he’s lucky enough to discover another hot disease? Do they call it Roiphe’s 2?”

“That would be lucky?” Naomi was drifting, fingers of her left hand working the iPad, her right the Air, both all over the net and some juicy SMSs rolling in on the iPhone. The juiciest: “Greetings from Tokyo, Naomi. Here’s the email address you wanted: hmatsuda@j.u-tokyo.ac.jp. Let’s talk soon.” The avatar in the message bubble was an actual photo of a pleasant-looking young Japanese woman that was framed like a painting; a little 3D-rendered brass plate at the bottom of the antiqued frame bore the signature “Yours, Yukie.”

Nathan was himself drifting into an imagined conversation with Dr. Barry Roiphe: “It helps with the research grants if your particular field of study touches a public nerve, don’t you think?”

“Is that it?” said Naomi. “Is that your hook? Roiphe’s 2: The Sequel?” Naomi was never intentionally cruel unless attacked, but when she was browsing, her attention thinned out into dismissiveness. But Nathan was really pitching his story to Roiphe, not Naomi.

“But it’s a great hook. I mean, it’s about medical fame and all that comes with it. It’s about the politics of medical grant-giving, repression from the religious right, etcetera. It’s about becoming a household name that’s more feared than Creutzfeldt ever was. What kind of man would want that fame? Would he get depressed when they found a cure and his name disappeared from the front pages?”

“It’s workable. Will it get too sensational? Have you placed it?”

“It’s another spec piece. Self-financed. Feels like The New Yorker , though, doesn’t it? ‘Annals of Medicine’?”

“Everything feels like that to you.”

“This is different.”

“Something about it is driving you.”

“Something. Must be.”

Triggered by the Yukie text, Naomi had quickly left Roiphe to unearth new Arosteguy crime-scene pages, all of them murky and suggestive of viral infections and weird Russian and Chinese spoofed URLs. That the pages themselves should feel diseased and virulent seemed appropriate, even oddly comforting. As though tracing her thoughts directly through her fingertips into its touchscreen, her iPad (she named it Smudgy) disgorged a close-up of Célestine’s severed head in the small refrigerator of the Arosteguy apartment.

“Oh, god,” said Naomi. “Oh… I just got another Arosteguy atrocity hit. I think the killer must have taken these photos himself. I don’t see any crime-scene guys around in them. But who posted them? I’m sending you that URL too.”

Nathan stood up and stretched. Something resembling a flight announcement was resonating through the lounge. It wasn’t his flight, but he held the phone out a bit to pick up the metallic garble for authenticity and then brought the phone back to his mouth. The disease dissonance was getting to him. “Well, maybe I’ll look at them in Toronto. Gotta go now. They’re calling my flight. Adore you. Don’t crumble.”

“ Je t’adore aussi. ” Naomi touched the red End button, and was instantly back in the Arosteguy apartment.

NATHAN GOT OUT OF A pumpkin-and-mint-green Beck cab in Toronto’s Forest Hill Village in front of the Coach Restaurant, a faded greasy spoon with the graphic of a silhouetted coach-and-four hanging over the door. Seniors leaning on walkers shuffled, a few girls in gray-and-burgundy uniforms from nearby Bishop Cornwall School drifted in and out. Carrying no camera, no visible recording device of any kind, he walked in through two sets of doors and stood by the vintage National cash register—embossed brass, color-coded glass keys, marble and wooden base.

A man who could be one of his own senior customers came slowly up some back stairs and approached him. “Can I help you?” he said, dropping a pad of order forms behind the ornate machine and punching the orange No Sale key. The National’s cash drawer slid open and a bell chimed.

“Is Dr. Roiphe here?”

The man—manager? owner?—smiled a wry, snorty smile without looking up and lifted a hinged lead-weighted bill holder so that he could riffle through the banknotes in one of the drawer’s cubbies. “You think this is a doctor’s office?”

Nathan played it straight. “I’m supposed to meet him here, but I don’t see him. Dr. Barry Roiphe.”

“If you don’t see him, then you’re blind,” said the man, not looking up but sticking an index finger into the air.

Читать дальше

Конец ознакомительного отрывка

Купить книгу

![David Jagusson - Fesselspiele mit Meister David [Hardcore BDSM]](/books/486693/david-jagusson-fesselspiele-mit-meister-david-har-thumb.webp)