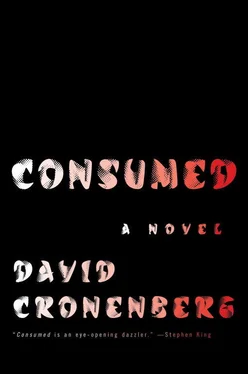

“They roam the earth looking for a doctor who will cut off a perfectly good arm or leg. An arm and a leg.”

“Or else they do it themselves with a chainsaw or a shotgun. Yeah. What’s it called?”

“Apotemnophilia.”

“Yeah. Body dysmorphic disorder, on the street.”

“Psychotherapeutic amputation.”

“Amputee identity disorder, with a twist of bioethics. It sounds juicy.”

“Speaking of ethics,” said Nathan, getting very close to her with the camera, “I believe I might be experiencing a touch of acrotomophilia. What should I do about it?”

“Hmm,” said Naomi uneasily, “I got the philia part.”

“A sexual attraction to amputees.” Nathan started to nuzzle her thighs.

Naomi whipped off the sheet and sat up. “I think you just managed to creep me out.” She held out her hand. “Gimme my camera back.”

“Aw.”

“I don’t do medical. You do medical, remember? I do crime. It’s cleaner.”

“Sometimes hard to separate them. But I thought you were giving me your camera. You were going iPhone solo, remember? I could use a backup.”

Naomi snapped her extended hand at him and Nathan gave her the camera. She immediately started to delete the photos.

“I think you’ve just rejected my pitch, and that is a crime,” said Nathan.

Naomi swung off the bed and started fretting the Nikon back into its roller. She spoke into the wall with her back to him. “Hey, aren’t you supposed to be going to Geneva for that… what was it? Worldwide Genital Mutilation Conference? Honestly, I think that’s more interesting than the amputation thing. There were so many articles about it for a while, then it tanked into hotness oblivion. It’s interesting about diseases, how they peak and tank. The politics of genital mutilation, now, that’s endlessly hot.”

“Thanks for the encouragement. I was thinking that my apotemnophilia piece would segue into that exact meditation. But never mind. The Geneva mutilation piece is off. No, I stay here in this hotel and finish the Hungarian thing, just in case there’s something in Europe I missed and have to pick up. I email it to my agent, shamelessly begging him to get me The New Yorker —”

“That’s still Lance, isn’t it?”

“It is the same old Lance. Then maybe I just go home to NYC. To where you aren’t.”

“I hate that part.”

“The New Yorker part?”

“The part where we say goodbye,” said Naomi, now sitting on the floor and playing with her new iPhone, still not looking at him.

Nathan stood up and leaned against the windowsill. “And you leave me alone in yet another hotel room,” he said.

Naomi looked up and flinched, almost startled to see him, as though she had just discovered an exotic bird at the window. Using the High Dynamic Range option, she took his flashless backlit picture with the phone. “I leave you desolate and alone. And I go back to Paris.”

NATHAN WAS FINISHING UP his solitary room-service meal. On a website called mediascandals.comwas a page devoted to Dr. Zoltán Molnár. His iPhone quavered and he answered it. “Hi, it’s Nathan.”

A very little female voice: “Nathan?”

“Yes?”

“It’s me. It’s Dunja.”

“Dunja? Where are you?”

“I’m at home. You know. Somewhere in Slovenia.”

“Yeah.” An awkward pause. Her voice was too little for comfort. “How are you?”

Dunja inhaled raggedly, suggesting to Nathan that she had been crying just before she called him. “Nathan, I think I gave you a disease. I’m so sorry.”

“A disease? You mean, literally?”

“Roiphe’s, Nathan. Roiphe’s disease. Dr. Molnár just phoned to tell me. It showed up by accident in some tests…” Her little voice hung there, suspended, weightless.

Almost without thought, or rather exactly like thought involving memory and information, Nathan was googling Roiphe’s disease and within seconds was downloading data into the conversation. Fingers flying and swiping.

“Roiphe’s?” said Nathan, net-borrowed argument tinting his tone. “Nobody’s had Roiphe’s since 1968.”

Dunja’s tone was the flattened tone of unassailable logic. “I’ve been immune-suppressed for a long time, and I have it. And so do you, now, I think. Probably.”

“The Roiphe’s survived all that radiation?”

“Radiation is not a treatment for Roiphe’s.”

“No,” said Nathan, “I see that.”

“You… you see that? On your computer? On the internet?”

A photo of Dr. Barry Roiphe on the cover of Time magazine, May 1968. He looked lanky and shy, a bespectacled Jimmy Stewart. The caption, in screaming yellow, read, “Dr. Barry Roiphe: Sex and Disease.” Dunja began to sob huge, liquid, globular sobs. For a moment, Nathan thought the sobs were coming from Dr. Roiphe himself, his apologetic, twisted grin now morphing into a rictus of grief and shame.

“I wonder whatever happened to him?” said Nathan.

“Who?” said Dunja, amid shudders.

“Roiphe. Dr. Barry Roiphe.”

NATHAN WAS HAVING A PEE, and it hurt. He talked to the pain: “Ow, fuck, ow, shit, that really hurts! Barry, Barry, what did I do to you?” The pee dribbled to an uncertain halt, then dripped morosely. Nathan shook his penis angrily and reached over to his shaving-kit bag. He took out a large magnifying glass with a ring of battery-operated LEDs, swiveled around to the sink, flicked on the LEDs, flopped his penis over the edge of the basin, and examined its tip. The word suppurating came to mind. “Fuck,” said Nathan. “Fuck, fuck, fuck!”

Back in the Schiphol Airport Lounge, despondent, he sat with laptop closed while others browsed with professional intensity. He hadn’t finished his Hungarian piece, his Slovenian, Dunja piece. The hotel room had started to feel like a disease ward, a holding compound for infectious disaster. His phone released the frog trill that said Naomi. He would have to consider changing her ringtone. The endangered frog species thing. Spooky, symbolic, something not good. Slide to answer. “Yeah, hi. Nathan.”

“I hear airport. Are you in an airport?”

“Yeah. Checked out early. You home?”

“Well, the Crillon. Not exactly my home away from home. Comfy.”

“I’ll bet. You sound edgy.”

On Naomi’s laptop was a grid of several horrific black-and-white photos under the heading “Arosteguy Crime Scene Images.” The photos showed the torso of Célestine Arosteguy, which was missing various pieces: one breast, half a buttock, the soft area around the belly button. Bite-sized lesions everywhere. “I’m back in my room, and I’m alone and I’m freaked out.”

Nathan was surprised to hear Naomi mention being alone, something she never did; with social media, net, phone, camera, recorder, she never seemed to feel alone. “Yeah? How come?”

“Oh, the CSI photos of Célestine Arosteguy. They’re hideous. How could the guy do that? I just can’t believe it. He’s such an attractive character, but… I dunno. Maybe. God. I’m sending you the URL.”

“Maybe don’t,” said Nathan. An African lady with a pushcart came around cleaning up bottles, cups, cans, newspapers. She took Nathan’s cappuccino before he was finished with it. “I’m not in the mood.”

Naomi got up from the desk chair and twirled onto the bed. She got under the duvet with all her clothes on, including shoes. “I need your advice, Than. You have to see this stuff. I can’t have it in my head all by myself. He ate pieces of her. I mean, I knew that, but now I’m seeing it.”

Nathan lifted the lid on his own Air, the third generation one with no SD card slot. It was actually Naomi’s hand-me-down. She needed that slot, she said. Needed it for photos, especially now that those little cards had become ubiquitous, even on pro cameras. He couldn’t bring himself to press the power button. “Is this crushing loneliness I feel just for you, or is it really, underneath, the harsh metallic edge of existential longing?”

Читать дальше

Конец ознакомительного отрывка

Купить книгу

![David Jagusson - Fesselspiele mit Meister David [Hardcore BDSM]](/books/486693/david-jagusson-fesselspiele-mit-meister-david-har-thumb.webp)