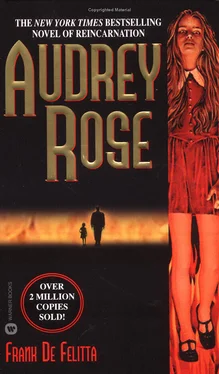

Ivy’s temperature had returned to normal soon after their arrival, and her hands, which Janice scrupulously medicated and bandaged each morning and evening, were beginning to heal. Thus far she had been spared the ordeal of the nightmares, which, to Janice, was a mixed blessing since this only confirmed Elliot Hoover’s theory of their origin.

Possibly the biggest shock was Bill’s reaction when she called him that first morning. He accepted each of her bombshells calmly and quietly, making no real protest, but probing her on every detail of her evening with Elliot Hoover: what he did upon entering, how long it took for him to quiet Ivy, what he said to Janice afterward, how long he remained, and what his parting words were. He thought her decision to flee to Westport was a good one; was glad they hadn’t come to Hawaii since it was hot, sticky and dull; told her to stay put until he arrived, which would probably be just after the weekend as he was cutting out the trip to Seattle, and screw Pel.

Monday, the day before Bill was to arrive, the storm drifted out to sea and, like a curtain being drawn across a child’s painting, disclosed a big, yellow, make-believe sun in a sky of azure blue.

The morning was a special gift for Ivy.

As they trudged along the water line, gingerly sidestepping the larger breakers, Janice rejoiced to see a faint tint of pink return to Ivy’s pale cheeks and hoped her appetite would return as well. They walked barefoot down miles of beach, seeking treasure given up by the sea during the storm. The booty presented itself to them in a continual line at the water’s edge, like a long counter of goods at the dime store. Shells, crustaceans, rocks, pebbles, sea plants, bits of driftwood, punctuated by larger set pieces—cruciforms of tree limbs, massive pilings, acres of bubbly seaweed—a variety of manufactured oddments: sea-weathered boards, bricks, and sundry bottles and rusted cans, their labels and messages obscured by tides and time.

“Look, Mommy!” Ivy called. “It’s dead!”

Janice, who had been lagging some distance behind, now approached to find her daughter squatting at the water’s edge over a large dead fish. Huge bites had reduced its flesh to the skeleton. A small shell had found a home in its eye socket.

“Come away from it,” Janice gently ordered and, taking Ivy’s hand, quickly led her past the mutilated carcass.

“It looked so— dead ,” Ivy said, incredulous.

“Dead is dead,” Janice lightly replied.

“Is that how people look when they die?”

“People look like people, not like fish.”

“I mean, all stiff and—broken?”

“Sometimes. If the death is violent.”

“Like in a car accident?”

Janice felt her heart leap.

“Yes,” she replied, her voice faltering slightly. “Like in a car accident.”

“It’s awful dying like that.”

Janice said nothing.

“Sometimes I have dreams about it,” continued Ivy.

Janice bit her lip. Then: “What kind of dreams?”

“Oh. Dying dreams.”

“In a car accident?”

“Sometimes. Sometimes I dream I’m dying in my bed. And everybody’s standing around me and crying. Bettina says the living suffer more than the dead. Her mother still suffers.”

“Do you have these dreams a lot?”

“No. Just sometimes.”

They walked a bit in silence.

“Will you mind very much?” Ivy asked wistfully.

“Mind?”

“Dying.”

“Yes.” Janice’s voice was heavy, stark. “I’ll mind very much.”

“I suppose I will, too,” Ivy said simply. “Especially if it’s in a terrible car accident.”

The conversation ended, leaving Janice to battle the rattling crash of the breakers with her own pounding heart.

There could be no doubt.

No doubt at all.

Audrey Rose’s terrors were beginning to leak into Ivy’s waking thoughts.

For a week, her daughter had been free of nightmares.…

The week away from Hoover.…

Audrey Rose sensed her father’s presence.…

—“Wanting! Needing! Crying out for my help! For MY help!”

His proximity alerted Audrey Rose, brought on the cruelly punishing nightmares.…

Away from Hoover there would be no nightmares.…

She must do everything in her power to keep Elliot Hoover away from her child.…

Somehow, she must think hard, and find a way to keep them apart … forever—

On their return to the cottage they passed a group of uniformed girls about Ivy’s age, sifting and sorting among the sea forms. A nature study class, Janice surmised, private, probably parochial, and very expensive. A middle-aged woman, not a nun, was seated nearby on a camp chair, attending her brood. There was an exchange of smiles between Janice and the woman as each paid tribute to the glorious morning, while Ivy squatted among the girls and became part of the class.

The scene was idyllic, restful, secure, an obvious and perfect answer.

“No!”

“Why not?”

“No discussion, Janice, I’m not buying—”

“Why not?”

“I’m not going to let this guy break up my family, that’s why not.”

Bill had rented a car at the airport and had driven directly to Westport, arriving just after 10. p.m. With Ivy safely asleep, they stood on a tuft of knoll a few paces away from the cottage, within sight of the moonspeckled waters of the Sound.

“I happen to like our life the way it is,” Bill continued hotly. “All of us together under the same roof. I’m surprised to hear you suggest such a nutty idea. Correction: I’m not that surprised. You’re really sold on this guy.”

“What does that mean?”

“You let him in, didn’t you? You let him help you—wash your wounds, take care of things, isn’t that what you told me?”

“I did it because I had to do it—”

“You didn’t have to do it—you could have waited for Kaplan!”

“I couldn’t—For God’s sake, I was there, you weren’t! Ivy was going crazy, I was afraid she’d kill herself—I had to let him in because only he could help her! Is it possible you still don’t understand that?”

“Right, Janice—on that point we part company. To me, Elliot Hoover is no miracle man. To me, he’s a misguided nut who seems to have made a hell of an impression on my wife!”

Janice shut her eyes and flexed her hands. Her voice, kept soft, was filled with shocked disbelief.

“You’re right, he’s made a hell of an impression on me. He’s scared me half to death; that’s what he’s done. Most of the time I’m so scared I can’t think straight. He’s got me talking to myself when I’m not talking to priests or screaming to God on my knees. He’s got me drinking in the mornings and stealing off in the dead of night to escape from him. Not because I’m afraid he’s a nut, but because I know he’s sane. Because I believe what he believes is true. Because I accept the fact that our child is the victim of some cosmic screw-up, and as long as she is near him, she’s in terrible danger of losing her life.”

Janice was trying not to cry, but could not stop the tears from coming.

“But the most terrible and frightening thing of all is that I’m completely alone in all this … that with all you’ve seen and heard, with all the evidence clearly stated before your eyes and ears, you still choose to ignore it. Bill, we’re in trouble! Sooner or later you’ve got to come out from under that fig leaf of yours and face it!”

Janice was sobbing now, but Bill made no move to hold her or soothe her. His face took on a masklike appearance.

“Okay, you’ve had your say. Now let me have mine.” The voice was grave, subdued. “To begin with, what you believe, I can never believe. Even if Hoover took me on a personal tour through St. Peter’s Gate and gave me a point-of-sales pitch, I still wouldn’t believe it. It’s not my reality. Although I will admit the day I left you and went to the airport my head was twisting and turning in every direction. I was glad to be leaving the whole mess behind me—you, Ivy, Hoover, all the sick bullshit we’ve been going through. Imagine. Me, model father, glad to be getting away from my own wife and child, whom I love more than life itself. But that’s the way I felt—glad and guilty, glad and guilty, glad and guilty, halfway across the country.

Читать дальше