Atcha,

” and I say, “

Atcha

,” with a laugh,

atcha

meaning okay.

The woman of the house scours the floor with sand. She rises when we enter and draws her shawl up over her head. Her hair is just like her daughter’s hair, long, in a braid, parted in the middle, and she wears a huge ring in her nose, as well as earrings and big silver bracelets on her ankles. Prana has sweet gold earrings in her ears, and there is a lovely jewel that falls from the long sari that the old lady wears over her head.

The woman’s name is Rama, and she looks to be having another baby.

The old lady enters the house, and her hair, long like the other women, is absolutely white. Her name is Shira, she seems to be the grandmother, and she wears the

kabja,

the blouse which covers the top of the body, and a loose-fitting petticoat, the

chania,

and over all is the eternal sari. She still has the brass pot on her head, but now she removes it, and we all sit on the floor where there is a meal. We eat

chapati

, the bread. It has been freshly baked for this meal and is served hot.

At the meal, too, are Uncle Chupar, Aunt Kastori, and Shakur, their son. These Indians live like many Indians in the villages, in what they call joint families. Almost like a miniature commune. All the property is communally owned, and the earnings of all the individual members are thrown into a common pool. There is great emotional security, and there is great economic security. If we think it does not offer much privacy or solitude, we must think only of their religion and how it invites them to go into themselves for privacy and solitude.

And later:

The family Pachali’s day begins at 4

a.m.

We bathe in icy cold water, and prayers are begun. The women join in the meditations but soon get down to household chores, churning butter, making buttermilk, leaving the men to continue with their meditations and prayers.

There are daily rituals which are accomplished by every member of the family. The first is

Bhuta Yajna,

an offering of food to the animal kingdom, symbolizing man’s realization of this obligation to less evolved forms of creation. In this way we come to understand instinctively that the weaker animals are also tied to a body identification as we are, but they do not have the quality of reason that we have. So as we help those that are weaker than ourselves, we can feel sure that we will be comforted in like manner by higher, unseen beings. That is the first form of daily worship. The second form is a ritual of silent love, silent love for nature. This is the way we surmount the inability to communicate with earth, sea, and sky. The other two daily

yajnas

are

Pitri

and

Nri,

these being offerings to ancestors so that daily we may acknowledge our debt to past generations, since it is their wisdom that has brought the light on us today.

I observe Amdhu and Rama and the real bond of love that exists between husband and wife. They treat each other with great gentility, although they are not openly affectionate in public or in front of their children. Rama sacrifices, at all times, for Amdhu and her children, keeping them the center of her universe and serving them at all times. She is concerned for Amdhu’s religious progress, feeling that the deeds she carries out for him will help him progress toward God. There is also a very close attachment between Amdhu and his daughter, Prana. Until puberty, she is allowed to accompany him on all male gatherings. With the knowledge that she will be sent to another home at marriage, she’s treated with indulgence by her father.

Arun, like all boys his age, spends more and more time outside the women’s quarters, in the vicinity of the men, in the company of his father and uncles who indulge him. But Amdhu always maintains a certain formality with him. The desire for sons is great, for only a son can adequately perform the death rites and the annual ceremony that assures peace to his father’s soul.

And so at all times death is looked upon quite openly with a sense of responsibility, planning, and a knowledge that every day lived leads toward that death which, in turn, will ensure a worthy progression to the next life.

And then:

I see great poverty, pain, sickness, drought, famine. Yet, in the midst of calamity, I see life progress with joy and love, with great care, and with great reverence.

The family is a microcosm of God’s world.…

Two large paper clips were necessary to fasten the thick group of pages that led to the next entry, which, surprisingly, found Hoover in a different part of India—in the forests of the south. For some reason he had left the Pachali family and either did not think it important enough or did not want Janice to know why. The two paper clips were all that barred her from learning more. Without hesitation, she flicked them off and renewed her relationship with Amdhu, Arun, Prana, and the rest of the family.

The drought continues. Failure of the monsoon to arrive on time makes the difference between abundance and blight. The entire village suffers. What few food stores are left are carefully divided between all the villagers.

Rama’s twins, who are just over a year old, cry a great deal, the girl more than the boy, since Rama favors him, nurses and feeds him first while the girl gets the leftovers, which is very little.…

The boy Khwaja, cries, but the girl, Sarojini, no longer cries. Prana, too, is ill from hunger, as is Rama, since the greater portion of what little food there is must go to the men. There is no hostility in this seemingly callous act of willful deprivation. It is simply part of a deeply ingrained tradition. In every village family, the women are fed last.…

Things are critical.…

On hands and knees, we all scour the parched fields for vagrant roots and seeds.…

A child in the village has died, and two others are soon to die. The family left this morning with the child’s body for the Ghats at Benares, eighteen kilometers to the north. Wrapped in white linen, the tiny form of the dead girl seemed to tremble with life as the cart trundled over dry clods of earth. The entire family pulled and pushed the cart. It will take them all day and all night to reach Benares.…

Prana has stopped speaking. Her large eyes can only stare at me. I must try to rehabilitate her and the village with whatever I possess. For two years now, I have not thought of the money or any of the ways and means of the life I left. But now I must think about it. And act!

Benares. Heat at 118 degrees. Sidewalks and streets covered with prostrate bodies, sacred cows chewing on coconut husks.

I have been here five days now, living in the transients’ settlement down by the riverbanks. Rejected air-conditioned hotel. Should have rejected American meal (Southern fried chicken and apple pie, first in two years). Made me violently ill.…

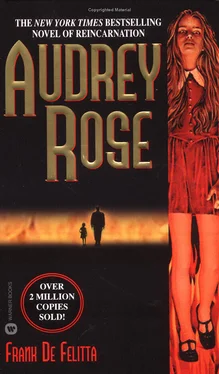

I am waiting for Barclay’s Bank to receive a wire from their correspondent in New York City approving my credit. I have contacted a man—shifty fellow—regarding grain stores which are black-market. He promises me vans will deliver supplies immediately that money, in American dollars, is received. I put my faith in him, reluctantly, but what choice have I? I have bargained for eight vanloads of rice, flour, and food grains for planting. They will be distributed among our own village and the neighboring villages, stretching the food as far as it will go. It will take all the money from the accident benefit to accomplish this. I like to think that Sylvia and Audrey Rose would approve.…

Strong ocean winds, lashing rains, and an extreme drop in temperature. The monsoon has come. With the suddenness and force of an avenging god. In minutes, the streets of Benares are flooded. The river is forced hundreds of yards beyond its banks. I hear that some of the villages to the south have become mudholes in the space of a day. There is no traffic, trucks, carts, cows, or people, as the roads are impassable.…

Читать дальше