One of the reports went on to say that the clothes she’d been wearing had been purchased in one of the city’s larger department stores. All of her clothes — those she wore and those found in her apartment — were rather expensive, but someone at the lab thought it necessary to note that all her panties were trimmed with Belgian lace and retailed for twenty-five dollars a pair. Someone else at the lab mentioned that a thorough examination of her garments and her body had revealed no traces of blood, semen, or oil stains.

The coroner fixed the cause of death as strangulation.

It is amazing how much an apartment can sometimes yield to science. It is equally amazing, and more than a little disappointing, to get nothing from the scene of a murder when you are desperately seeking a clue. The furnished room in which Claudia Davis had been strangled to death was full of juicy surfaces conceivably carrying hundreds of latent fingerprints. The closets and drawers contained piles of clothing that might have carried traces of anything from gunpowder to face powder.

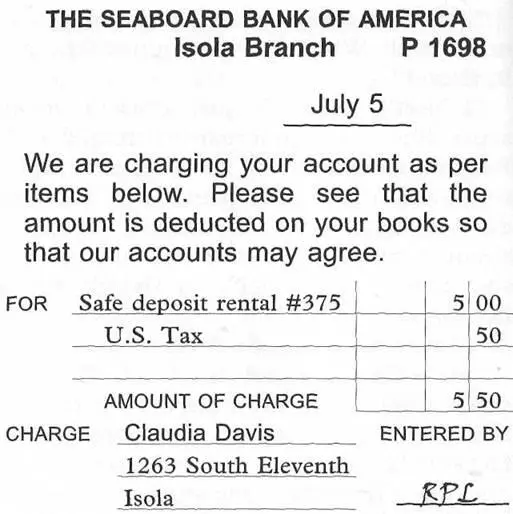

But the lab boys went around lifting their prints and sifting their dust and vacuuming with a Söderman-Heuberger filter, and they went down to the morgue and studied the girl’s skin and came up with a total of nothing. Zero. Oh, not quite zero. They got a lot of prints belonging to Claudia Davis, and a lot of dust collected from all over the city and clinging to her shoes and her furniture. They also found some documents belonging to the dead girl — a birth certificate, a diploma of graduation from a high school in Santa Monica, and an expired library card. And, oh, yes, a key. The key didn’t seem to fit any of the locks in the room. They sent all the junk over to the 87th, and Sam Grossman called Carella personally later that day to apologize for the lack of results.

The squadroom was hot and noisy when Carella took the call from the lab. The conversation was a curiously one-sided affair. Carella, who had dumped the contents of the laboratory envelope onto his desk, merely grunted or nodded every now and then. He thanked Grossman at last, hung up, and stared at the window facing the street and Grover Park.

“Get anything?” Meyer asked.

“Yeah. Grossman thinks the killer was wearing gloves.”

“That’s nice,” Meyer said.

“Also, I think I know what this key is for.” He lifted it from the desk.

“Yeah? What?”

“Well, did you see these canceled checks?”

“No.”

“Take a look,” Carella said.

He opened the brown bank envelope addressed to Claudia Davis, spread the canceled checks on his desk top, and then unfolded the yellow bank statement. Meyer studied the display silently.

“Cotton found the envelope in her room,” Carella said. “The statement covers the month of July. Those are all the checks she wrote, or at least everything that cleared the bank by the thirty-first.”

“Lots of checks here,” Meyer said.

“Twenty-five, to be exact. What do you think?”

“I know what I think,” Carella said.

“What’s that?”

“I look at those checks. I can see a life. It’s like reading somebody’s diary. Everything she did last month is right here, Meyer. All the department stores she went to, look, a florist, her hairdresser, a candy shop, even her shoemaker, and look at this. A check made out to a funeral home. Now who died, Meyer, huh? And look here. She was living at Mrs. Mauder’s place, but here’s a check made out to a swank apartment building on the South Side, in Stewart City. And some of these checks are just made out to names, people. This case is crying for some people.”

“You want me to get the phone book?”

“No, wait a minute. Look at this bank statement. She opened the account on July fifth with a thousand bucks. All of a sudden, bam, she deposits a thousand bucks in the Seaboard Bank of America.”

“What’s so odd about that?”

“Nothing, maybe. But Cotton called the other banks in the city, and Claudia Davis has a very healthy account at the Highland Trust on Cromwell Avenue. And I mean very healthy.”

“How healthy?”

“Close to sixty grand.”

“What!”

“You heard me. And the Highland Trust lists no withdrawals for the month of July. So where’d she get the money to put into Seaboard?”

“Was that the only deposit?”

“Take a look.”

Meyer picked up the statement.

“The initial deposit was on July fifth,” Carella said. “A thousand bucks. She made another thousand-dollar deposit on July twelfth. And another on the nineteenth. And another on the twenty-seventh.”

Meyer raised his eyebrows. “Four grand. That’s a lot of loot.”

“And all deposited in less than a month’s time. I’ve got to work almost a full year to make that kind of money.”

“Not to mention the sixty grand in the other bank. Where do you suppose she got it, Steve?”

“I don’t know. It just doesn’t make sense. She wears underpants trimmed with Belgian lace, but she lives in a crumby room-and-a-half with bath. How the hell do you figure that? Two bank accounts, twenty-five bucks to cover her ass, and all she pays is sixty bucks a month for a flophouse.”

“Maybe she’s hot, Steve.”

“No.” Carella shook his head. “I ran a make with C.B.I. She hasn’t got a record, and she’s not wanted for anything. I haven’t heard from the feds yet, but I imagine it’ll be the same story.”

“What about that key? You said ...”

“Oh, yeah. That’s pretty simple, thank God. Look at this.”

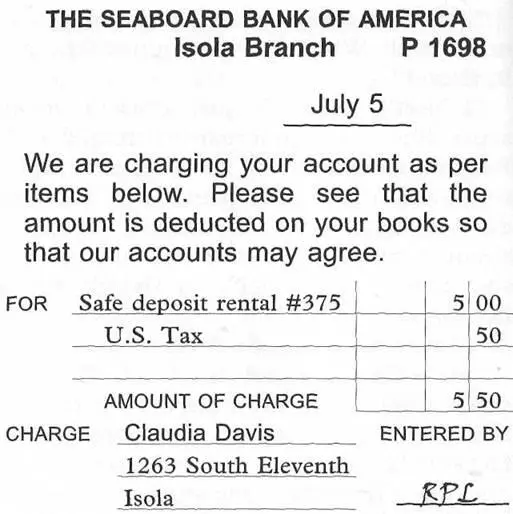

He reached into the pile of checks and sorted out a yellow slip, larger than the checks. He handed it to Meyer. The slip read:

“She rented a safe-deposit box the same day she opened the new checking account, huh?” Meyer said.

“Right.”

“What’s in it?”

“That’s a good question.”

“Look, do you want to save some time, Steve?”

“Sure.”

“Let’s get the court order before we go to the bank.”

The manager of the Seaboard Bank of America was a bald-headed man in his early fifties. Working on the theory that similar physical types are simpático, Carella allowed Meyer to do most of the questioning. It was not easy to elicit answers from Mr. Anderson., the manager of the bank, because he was by nature a reticent man. But Detective Meyer Meyer was the most patient man in the city, if not the entire world. His patience was an acquired trait, rather than an inherited one. Oh, he had inherited a few things from his father, a jovial man named Max Meyer, but patience was not one of them. If anything, Max Meyer had been a very impatient if not downright short-tempered sort of fellow. When his wife, for example, came to him with the news that she was expecting a baby, Max nearly hit the ceiling. He enjoyed little jokes immensely, was perhaps the biggest practical joker in all Riverhead, but this particular prank of nature failed to amuse him. He had thought his wife was long past the age when bearing children was even a remote possibility. He never thought of himself as approaching dotage, but he was after all getting on in years, and a change-of-life baby was hardly what the doctor had ordered. He allowed the impending birth to simmer inside him, planning his revenge all the while, plotting the practical joke to end all practical jokes.

When the baby was born, he named it Meyer, a delightful handle which when coupled with the family name provided the infant with a double-barreled monicker: Meyer Meyer.

Читать дальше