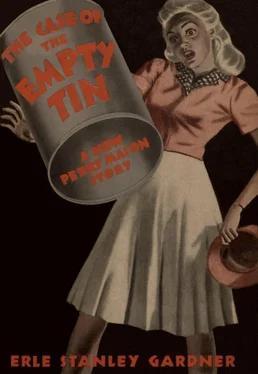

Erle Stanley Gardner

The Case of the Empty Tin

FLORENCE GENTRIE — Mrs. Arthur Gentrie, mother of three with an executive’s eye for detail

HESTER — her maid, who may or may not be stupid

REBECCA GENTRIE — her sister-in-law, an old maid with a fondness for crossword puzzles

ARTHUR GENTRIE — her husband, who owns a hardware store and can sleep through anything

JUNIOR — her son, 19, who won’t tell all he knows

PERRY MASON — criminal lawyer who is not averse to compounding a felony to solve a murder

DELLA STREET — his attractive secretary whose gun moll activities cause complications

RODNEY WENSTON — tall, handsome playboy pilot with an odd lisp and loquacious charm

GOW LOONG — inscrutable, soft-spoken, quick-moving Number One boy of

ELSTON A. KARR — rugged individualist with an Oriental angle of approach and secrets to keep

JOHNS BLAINE — who’s always in the background and calls himself “a sort of nurse”

LIEUTENANT TRAGG — quiet, efficient member of the Homicide Squad who knows Mason of old

DELMAN STEELE — the Gentries’ boarder who has made himself a member of the family

PAUL DRAKE — detective with a lot of explanations to make and sleep to catch up on

OPAL SUNLEY — a pretty young stenographer who wants to stay out of the papers

MRS. SARAH PERLIN — housekeeper, whose disappearance helps start it all

DORIS WICKFORD — exotic ex-actress who reads the “Personal” columns and has a claim to make

L. O. SAWDEY — a busy doctor who holds an important key to the solution of the murders

Mrs. Arthur Gentrie managed her household with that meticulous attention to detail which marks any good executive. Her mind was an encyclopedic storehouse of various household data. Seemingly without any mental effort, she knew when the holes which showed up in Junior’s socks were sufficiently premature to indicate a poor quality in the yarn. When her husband had to travel on business, she knew just which of his shirts had already been sent to the laundry, and could, therefore, be packed in his grip. His other shirts were scrupulously hand-laundered at home.

In her forties, Mrs. Gentrie prided herself on the fact that she “didn’t have a nerve in her body.” She neither ate so much that she bulged with fat, nor had she ever starved herself so as to become neurotic. Her hips weren’t what they had been twenty years ago, but she accepted that with the calm philosophy of a realist. After all, a person couldn’t keep house for a husband, three children, an old-maid sister-in-law, rent out a room, keep household expenses down, and still retain the slim silhouette of a bride. As Mrs. Gentrie herself expressed it, she was “strong as an ox.”

Her husband’s sister wasn’t much help. Rebecca obviously was not a bachelor woman, nor could she be described as an “unmarried relative.” She was very definitely and decidedly an old-fashioned maiden lady, a thin, tea-drinking, cat-loving, gossip-spreading, talkative, critical, yet withal a good-looking old maid.

Mrs. Gentrie didn’t rely on Rebecca for much help around the house. She was too slight physically to be of assistance with the work, and too scatterbrained to help with responsibilities. She had, moreover, frequent spells of “ailing,” during which there seemed to be nothing particularly wrong save a psychic maladjustment seeking a physical manifestation.

Rebecca did, however, keep the room which Mrs. Gentrie rented in order. At present this room was occupied by a Mr. Delman Steele, an architect. Rebecca had two hobbies to which she gave herself with that enthusiasm which characterizes one whose emotions are otherwise repressed. She was an ardent crossword-puzzle fan and an amateur photographer. A darkroom in the basement was equipped with printers, enlargers, and developing tanks, most of which had been built by Arthur Gentrie, who had a distinct flair for tinkering and loved to indulge the whims of his sister.

There were times when Mrs. Gentrie bitterly resented Rebecca, although she tried to fight against that resentment and always managed to keep from showing it. For one thing, Rebecca didn’t get along well with the children. In place of sympathizing with their youthful indiscretions, Rebecca sought to hold them to the standards by which one would judge a grown-up. This, coupled with the fact that she had an uncanny ability to mimic voices and enjoyed nothing better than watching the children squirm while she re-enacted some bit of their conversation over the telephone, introduced a certain element of friction into the household which Mrs. Gentrie found highly annoying.

Nor would Rebecca, who did excellent photographic work, ever take the trouble to get good pictures of the children.

On Junior’s nineteenth birthday, she had condescended to take a picture at Mrs. Gentrie’s urgent request. The ordeal had been as distasteful to Junior as it had been to Rebecca, and Junior’s picture showed it, which would have been bad enough, had it not happened that Rebecca, who was experimenting with some of the new photographic wrinkles, had made an enlargement on a sheet of paper which had been held on an angle. The result had been a picture which was similar to the distorted reflections shown in the curved mirrors of penny arcades.

There was nothing slow about Rebecca’s mental processes when dealing with anything that interested her. Nothing ever went on around the house which she didn’t ferret out. Her curiosity was insatiable, and the manner in which she ferreted out secrets from an inadvertent remark or some casual clue would have done credit to a really good detective. Mrs. Gentrie knew that Rebecca had consented to take care of Delman Steele’s room largely because she enjoyed snooping around through his things, but there was nothing Mrs. Gentrie could do about this, and, inasmuch as the cleaning was always done while Steele was away at the office, there wasn’t much chance he would ever discover Rebecca’s surreptitious activities.

Hester, the maid, who came in by the day, was a strong, stalwart, taciturn, childless woman who lived in the neighborhood. Her husband was an intermittent sufferer from asthma, but was able to get around, and had a job as night watchman in one of the laboratories where new-model planes were given wind-tunnel tests.

Mrs. Gentrie paused to make a mental survey of the house. The breakfast things had been cleared away. Arthur and Junior had gone to the store. The children were off at school. Hester was running small table napkins through the electric mangle, and Rebecca, at her perennial crossword puzzle, was struggling with the daily offering from the newspaper, a pencil in her hand, her dark, deep-set eyes staring in frowning concentration. Mephisto, the black cat to which she was so attached, was curled up in the chair, where a shaft of windowed sunlight furnished a spot of welcome warmth.

The morning fire was still going in the wood stove. The big tea kettle was singing away reassuringly. There was a pile of mending to be done in the basket and... Mrs. Gentrie thought of the preserved fruit in the cellar. It simply had to be gone over. Hester was always inclined to reach for the most accessible tin, and Mrs. Gentrie strongly suspected that over in the dark corner of the cellar there were some cans which went back to 1939.

She paused for a moment, trying to remember the location of a flashlight. The children were always picking them up. There was a candle in the pantry, but... She remembered there was a flashlight in Junior’s bedroom that had a clip which enabled it to be fastened to the belt She’d borrow it for a few moments.

Читать дальше