I have never had a man in my life, Rikard. Since you went to Berlin, after my parents died, I have lived alone, and I have chosen to live alone. I was a little in love with a man I met not so long ago, called William. He was from Mayfair in London. But nothing will ever happen between us, because I am sitting here now. Please don’t ask me about William, as it just upsets me .

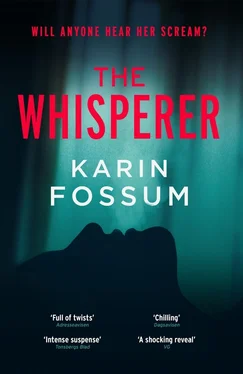

You heard my whispers on the phone, and perhaps it made you think. You may have read about people who have lost their voice box talking with the help of technology, in a distorted, mechanical voice. The sort of voice that frightens small children and gives them nightmares. Other people learn a technique whereby they swallow air, and then release it with a burp to create the sound of a word. I don’t want to talk with a voice like that. Even though the doctors encouraged me to. I have never been a beauty, but I did not want to make things worse by having a hideous voice. When you speak like that, using either air or a talk tool of some kind, people step back in alarm. But when you whisper, they lean in so they can hear. But I was talking about Adde, and he can only see me with one eye, but my goodness, does he stare. And I both like it and don’t like it. I don’t know what he sees or thinks, because he says nothing. But I can tell that he has drawn his own conclusions, even though he knows nothing about me. And I think I can safely say that I could surprise him .

You said you were in a big prison, with nearly six hundred inmates. I know the Stasi had many prisons in Berlin, is yours one of them? You must tell me all about your days, and nights as well. Tell me what you eat, tell me more about Peter and the priest. You must all be kind to them. Be kind and wish them well, and maybe they will find each other. But I know that you are kind, Rikard. I now keep the letter you wrote safe in the drawer of my desk, by the window. I often go over and open the drawer, just to make sure it is still there. I hold the envelope up to the light, and see your writing shine through. I will treasure your words like jewels and take them with me wherever I go. Not that I am going anywhere for a while, it will be a long time before I am allowed to walk the streets again or catch a bus, but your words will be with me in my dreams. From now on, let us think about each other every day, in the morning and evening. My dear boy, I only have eight square metres, but what more does a person need? A desk and a bed and a window, so the sun shines in on a good day. The cell makes me feel safe. I know where I am. It is impossible to get lost in eight square metres, but equally, it is impossible to hide. Now I am out where everyone can see me, like you. Tell me what you can see through your cell window. If you can see a patch of sky, then remember that I am serving my sentence under the very same sky .

With love from ,

Your mother

Out of the blue, Lars suggested that they should all go to the pub one evening.

‘Saturday, sometime after six? Just the four of us? I’ll book a table.’

Audun smiled politely and Ragna looked the other way.

‘It’s your birthday,’ Gunnhild said immediately.

Yes, it was, Lars admitted. His fortieth birthday, and the celebration he had had with his family, with tapas and red wine and speeches, was not what he had wanted.

‘I’ll pay for everyone,’ he said quickly. ‘Fish and chips.’

The shop closed at six o’clock on Saturdays, so they agreed to meet at Kongens Våpen at seven. The pub was on the south side of the river and very popular. It had a good reputation and was busy most nights. There was never any trouble, no fights or drunks, so they did not have a bouncer, and as far as anyone knew, the police had never been called. Lars had asked for a quiet corner, he assured them, glancing at Ragna, who smiled without looking at him. Considerate, always so considerate. She was just a burden. She could imagine the noise level in a pub on a Saturday night, and it was also the kind of place where they were likely to be showing a football match on the screen. She would not stand a chance. So she said no.

‘Yes,’ Lars said forcefully.

‘No,’ she whispered.

‘Yes,’ Gunnhild ordered.

Audun said nothing. He accepted the invitation with a small nod, but Ragna was distraught. She would not be audible in a pub where they played music, perhaps even sang Irish drinking songs. But if she said no again, all eyes would be on her. A no would make her colleagues even more worried about her, and she did not want that either. She could perhaps say yes and go with them for a short while, and then go home early. They would accept that.

On the bus, on the way there, she had several conversations with herself about what she might say that evening. The odd comment now and then when she could easily catch their attention. Everything was going very well for Rikard Josef. He had a lot to do at the hotel right now, in the run-up to Christmas. No, he wasn’t coming home, it was impossible for him at this time of year, given his senior position and responsibilities. Did he have a girlfriend? Were there any grandchildren on the way? Not that I know of.

And then she would look down at the table, abashed.

He’s only thirty. He doesn’t have time for that sort of thing, he has to do the accounts and wages in the evenings, and contact people high up in the business.

That was the kind of thing she would say, and her words would fall as lightly as that evening’s snow, with its big beautiful snowflakes. She also had a present for Lars. She had gone into Magasinet, the department store in town, and bought him a book, 1000 Proverbs and Sayings . On the title page, she had written: ‘YOU HAVE A VOICE. HERE ARE THE WORDS.’

She had been dreading it all day. Had huffed and puffed and sighed like a martyr facing an enormous challenge. She had tried to keep a smile on her face, but failed; she was worried about what might happen, was her head not a bit warm, was her brain about to melt again, would it escape, because then she would lose what little language she had. Would someone break into her house while she was out? Despite having locked and closed everything, she imagined her stalker would find a small opening somewhere, a crack or a gap where he could slip in like a poisonous gas. She had not heard anything from the police. Nor had she contacted them. Her report and the threat had no doubt been forgotten, they had other more important things to do. She would love to be able give them that — something spectacular that they had never seen before, but as she was not spectacular, she did not know how.

Gunnhild met her at the bus station on the other side of the bridge, and greeted her like a close friend, which she was not. But Ragna did soften. The enormous snowflakes landed on her shoulders and she did not brush them off, but left them to melt into her coat. She pretended that the crystals shone like glitter against the black material, and she definitely needed decoration. She loved the stillness of snow, it was compact, dense, and strangely cosy. She heard better and could be better heard herself.

‘I’ve never had fish and chips,’ she admitted to Gunnhild, speaking into her ear.

‘It’s good,’ Gunnhild said. ‘And the chef at Kongens Våpen is English, so he knows what he’s doing.’

Gunnhild hooked an arm through hers and pulled her along. Ragna had never been so close to Gunnhild. Had never felt her body in this way. They walked close together, hip to hip, through the streets, past all the low, wooden buildings which were warped and crooked, and not particularly well maintained, but all the more charming for it. Ragna knew that Irfan lived somewhere around here, it was cheaper than the other side of the river. And she presumed that his new shop was somewhere nearby, the one he had opened with his cousin, after the tax office had gone through his papers. Now there were two of them to keep the accounts. She was unfamiliar with the area, but now that she was walking through it, she understood his choice. This was where all the immigrants lived, and they would want to go to Irfan’s shop. She missed the flatbread that was so fresh there was condensation in the bag, and the jars of spicy sauces. Ragna could tell from the way Gunnhild was holding her arm that she felt responsible for her. On the one hand Ragna wanted to let herself be led like a child, but on the other, it annoyed her. I can walk, after all, she thought, and I can see, and I can hear. Then she regretted these thoughts and smiled happily at Gunnhild and brushed some snow off her sleeve. She thought of it as a caress, and could not remember the last time she had caressed anyone. Why had she not seized the opportunity to give William from London a sign of affection, a hand on his arm, when they stood so close on the pavement and she had the chance?

Читать дальше