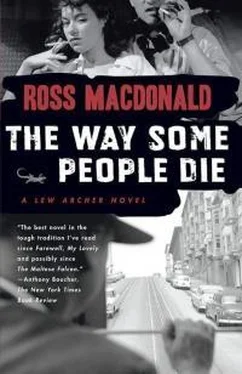

Росс Макдональд - The Way Some People Die

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Росс Макдональд - The Way Some People Die» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2010, Жанр: Крутой детектив, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:The Way Some People Die

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:2010

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:3 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Way Some People Die: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The Way Some People Die»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

The third Lew Archer mystery, in which a missing-persons search takes him "through slum alleys to the luxury of a Palm Springs resort, to a San Francisco drug-peddler's shabby room. Some of the people were dead when he reached them. Some were broken. Some were vicious babes lost in an urban wilderness.

The Way Some People Die — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The Way Some People Die», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

“You have.” Gary was using his gentle voice once more. “This isn’t very funny. It doesn’t make me laugh.”

“It isn’t funny. It has some funny elements, though–”

He cut me off again: “You’ve acted like a damn fool, and you know it. I could probably get an indictment and possibly make it stick–”

“The hell you could. I was just going to tell you the funniest thing of all. I shot Dalling at a range of one hundred and twenty miles. Pretty good for a .38 automatic that normally can’t hit a barn door at fifty paces.”

“Failing a murder indictment,” he went on imperturbably, “I could be very nasty about your failure to report discovery of the corpse. It happens I don’t want to be nasty. Colton doesn’t want me to be nasty, and I value his judgment. But you’re going to force me to be nasty if you go on talking like a damn fool on top of acting like one.” He chewed his upper lip. “Now what was that about an alibi?”

It struck me that vaudeville was dead. “At the time Dalling was shot, I was fifteen or twenty miles on the other side of Palm Springs, talking to a woman by the name of Marjorie Fellows. Why don’t you get in touch with her? She’s staying at the inn there.”

“Perhaps I will. What time was that?”

“Around three in the morning.”

“If you know that Dalling was shot at three, you know more than we do. Our doctor places it around four, give or take an hour.” He spread his hands disarmingly, as if to underline the fact of his candor. “There’s no way to determine how long he lived after he was shot, or exactly when he was shot. It’s evident from the blood that he lived for some time, though he was almost certainly unconscious from the slug in his cortex. Anyway, you can see how that plays hell with any possible alibi. Unless you have better information?” There was irony in the question.

I said that I had.

“You want to make a statement?”

I said that I did.

“Good. It’s about time.” He flipped the switch on the squawk-box on the corner of his desk, and summoned a stenographer.

My obligation to Peter Colton was growing too big for comfort. Apparently the conversation up to this point had been off the record. That suited me, because my performance had been painful. I’d bungled like an amateur when I found Dalling’s body; gambled and lost on the chance that Miss Hammond or Joshua Severn might tell me something important if I got to them before policemen did. Gary had driven that home, in spite of my efforts to talk around the point. Vaudeville was dead as Dalling, and the Rover Boys were as out of date as the seven sleepers of Ephesus.

Gary gave up his chair to the young male stenographer.

“Do you want it in detail?” I asked him.

“Absolutely.”

I gave the thing in detail from the beginning. The beginning was Dalling’s visit to Mrs. Lawrence, which brought me into the case. The night died gradually, bleeding away in words. The police stenographer filled page after page of his notebook with penciled hieroglyphics. Gary paced from wall to wall, still looking for a way out. Occasionally he paused to ask me a question. When I told him that Tarantine had taken my gun, he interrupted to ask: “Will Mrs. Tarantine corroborate that?”

“She already has.”

“Not to us.” He took a paper-bound typescript from his desk and riffled through it. “There’s nothing in her statement about your gun. Incidentally, you didn’t report the theft.”

“Call her up and ask her.”

He left the room. The stenographer lit a cigarette. We sat and looked at each other until Gary came back: “I sent a car for her. I talked to her on the phone and she doesn’t seem to object. She a friend of yours?”

“She won’t be after this. She has a queer old-fashioned idea that a woman should stick by her husband.”

“He hasn’t done much of a job of sticking by her. What do you make of Mrs. Tarantine, anyway?”

“I think she made the mistake of her life when she married Tarantine. She has a lot of stuff, though.”

“Yeah,” he said dryly. “Is she trying to cover for him, that’s what I want to know.”

“She has been, I think.” And I recited what she had told me about the early-morning visit to Dalling’s apartment.

That stopped him in his tracks. “There’s a discrepancy there, all right.” He consulted her statement again. “According to what she said this afternoon, she drove him straight over from Palm Springs to Long Beach by the canyon route. The question is, which time was she telling the truth?”

“She told me the truth,” I said. “She didn’t know then that Dalling was dead. When she found out that he was, she switched her story to protect her husband.”

“When did you talk to her?”

“Early this afternoon – yesterday afternoon.” It was four o’clock by my wristwatch.

“You knew that Dalling was dead.”

“I didn’t tell her.”

“Why? Could she have killed him herself, or set him up for her husband?”

“I entertained the possibility, but she’s crazy if she did. She was half in love with Dalling.”

“What about the other half?”

“Mother feeling or something. She couldn’t take him seriously; he was alcoholic, for one thing.”

“Yeah. Did she communicate all this, or you dream it up?”

“You wouldn’t be interested in my dreams.”

“Okay. Let’s have the rest of the statement, eh?” And he went back to filling the room with his pacing. It was ten to five when I finished my statement. The stenographer left the room with orders to have it typed as quickly as possible.

“If you’ve been leveling,” Gary said to me, “it looks very much like Tarantine. Why would he do it?”

“Ask Mrs. Tarantine.”

“I’m going to. Now.”

“I’d like to sit in if possible.”

“Uh-uh. Good night.”

She met me in the corridor, walking in step with Sergeant Tolliver.

“We’re always meeting in police stations,” I said.

“As good a place as any, I guess.” She looked exhausted, but she had enough energy left to smile with.

Chapter 26

I woke up looking for the joker that would freeze the pile and win the hand for me. It wasn’t under the pillow. It wasn’t between the sheets. It wasn’t on the floor beside the bed. I was climbing out of the bed to look underneath it when I realized that I had been dreaming.

It was exactly noon by my bedside alarm. A truck started up in the street outside with an impatient clash of gears, as if to remind me that the world was going on without me. I let it go. First I took a long hot shower and then a short cold one. The pressure of the water hurt the back of my head. I shaved and brushed my teeth for the first time in two days and felt unreasonably virtuous. My face looked the same as ever, as far as I could tell. It was wonderful how much a pair of eyes could see without being changed by what they saw. The human animal was almost too adaptable for its own good.

The kitchen was brimful of yellow sunlight that poured in through the window over the sink. I started a pot of coffee, fried some bacon, broke four eggs in the sizzling grease, toasted half a dozen slices of stale bread. After eating, I sat in the breakfast nook with a cigarette and a cup of black coffee, thinking of nothing. Silence and loneliness were nice for a change. The absence of dialogue was a positive pleasure that lasted through the second cup of coffee. But I noticed after a while that I was tapping one heel on the floor in staccato rhythm and beginning to bite my left thumbnail. A car passed in the street with the sound of a bus I was about to miss. The yellow sunlight was bleak on the linoleum. The third cup of coffee was too bitter to drink.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The Way Some People Die»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The Way Some People Die» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The Way Some People Die» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.