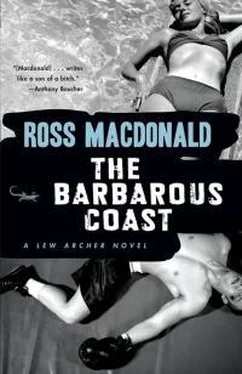

Ross Macdonald

THE BARBAROUS COAST

1956

THE CHANNEL CLUB lay on a shelf of rock overlooking the sea, toward the southern end of the beach called Malibu. Above its long brown buildings, terraced gardens climbed like a richly carpeted stairway to the highway. The grounds were surrounded by a high wire fence topped with three barbed strands and masked with oleanders.

I stopped in front of the gate and sounded my horn. A man wearing a blue uniform and an official-looking peaked cap came out of the stone gatehouse. His hair was black and bushy below the cap, sprinkled with gray like iron filings. In spite of his frayed ears and hammered-in nose, his head had the combination of softness and strength you see in old Indian faces. His skin was dark.

“I seen you coming,” he said amiably. “You didden have to honk, it hurts the ears.”

“Sorry.”

“It’s all right.” He shuffled forward, his belly overhanging the belt that supported his holster, and leaned a confidential arm on the car door. “What’s your business, mister?”

“Mr. Bassett called me. He didn’t state his business. The name is Archer.”

“Yah, sure, he is expecting you. You can drive right on down. He’s in his office.”

He turned to the reinforced wire gate, jangling his key-ring. A man came out of the oleanders and ran past my car. He was a big young man in a blue suit, hatless, with flying pink hair. He ran almost noiselessly on his toes toward the opening gate.

The guard moved quickly for a man of his age. He whirled and, got an arm around the young man’s middle. The young man struggled in his grip, forcing the guard back against the gatepost. He said something guttural and inarticulate. His shoulder jerked, and he knocked the guard’s cap off.

The guard leaned against the gatepost and fumbled for his gun. His eyes were small and dirty like the eyes of a potato.

Blood began to drip from the end of his nose and spotted his blue shirt where it curved out over his belly. His revolver came up in his hand. I got out of my car.

The young man stood where he was, his head turned sideways, halfway through the gate. His profile was like something chopped out of raw planking, with a glaring blue eye set in its corner. He said: “I’m going to see Bassett. You can’t stop me.”

“A slug in the guts will stop you,” the guard said in a reasonable way. “You move, I shoot. This is private property.”

“Tell Bassett I want to see him.”

“I already told him. He don’t want to see you.” The guard shuffled forward, his left shoulder leading, the gun riding steady in his right hand. “Now pick up my hat and hand it to me and git.”

The young man stood still for a while. Then he stooped and picked up the cap and brushed at it ineffectually before he handed it back.

“I’m sorry. I didn’t mean to hit you. I’ve nothing against you.”

“I got something against you, boy.” The guard snatched the cap out of his hands. “Now beat it before I knock your block off.”

I touched the young man’s shoulder, which was broad and packed with muscle. “You better do what he says.”

He turned to me, running his hand along the side of his jaw. His jaw was heavy and pugnacious. In spite of this, his light eyebrows and uncertain mouth made his face seem formless. He sneered at me very youngly: “Are you another one of Bassett’s muscle boys?”

“I don’t know Bassett.”

“I heard you ask for him.”

“I do know this. Run around calling people names and pushing in where you’re not wanted, and you’ll end up with a flat profile. Or worse.”

He closed his right fist and looked from it to my face. I shifted my weight a little, ready to block and counter.

“Is that supposed to be a threat?” he said.

“It’s a friendly warning. I don’t know what’s eating you. My advice is go away and forget it–”

“Not without seeing Bassett.”

“And, for God’s sake, keep your hands off old men.”

“I apologized for that.” But he flushed guiltily.

The guard came up behind him and poked him with the revolver. “Apology not accepted. I used to could handle two like you with one arm tied behind me. Now are you going to git or do I have to show you?”

“I’ll go,” the young man said over his shoulder. “Only, you can’t keep me off the public highway. And sooner or later he has to come out.”

“What’s your beef with Bassett?’ I said.

“I don’t care to discuss it with a stranger. I’ll discuss it with him.” He looked at me for a long moment, biting his lower lip. “Would you tell him I’ve got to see him? That it’s very important to me?”

“I guess I can tell him that. Who do I say the message is from?”

“George Wall. I’m from Toronto.” He paused. “It’s about my wife. Tell him I won’t leave until he sees me.”

“That’s what you think,” the guard said. “March now, take a walk.”

George Wall retreated up the road, moving slowly to show his independence. He dragged his long morning shadow around a curve and out of sight. The guard put his gun away and wiped his bloody nose with the back of his hand. Then he licked his hand, as though he couldn’t afford to waste the protein.

“The guy’s a cycle-path what they call them,” he said. “Mr. Bassett don’t know him, even.”

“Is he what Bassett wants to see me about?”

“Maybe, I dunno.” His arms and shoulders moved in a sinuous shrug.

“How long has he been hanging around?”

“Ever since I come onto the gate. For all I know, he spent the night in the bushes. I ought to have him picked up, but Mr. Bassett says no. Mr. Bassett is too softhearted for his own good. Handle him yourself, he says, we don’t want trouble with law.”

“You handled him.”

“You bet you. Time was, I could take on two like him, like I said.” He flexed the muscle in his right arm and palpated it admiringly. He gave me a gentle smile. “I was a fighter one time – pretty good fighter. Tony Torres? You ever hear my name? The Fresno Gamecock?”

“I’ve heard it. You went six with Armstrong.”

“Yes.” He nodded solemnly. “I was an old man already, thirty-five, thirty-six. My legs was gone. He cut my legs off from under me or I could of lasted ten. I felt fine, only my legs. You know that? You saw the fight?”

“I heard it on the radio. I was a kid in school, I couldn’t make the price.”

“What do you know?” he said with dreamy pleasure. “You heard it on the radio.”

I LEFT my car on the asphalt parking-lot in front of the main building. A Christmas tree painted brilliant red hung upside-down over the entrance. It was a flat-roofed structure of fieldstone and wood. Its Neutraesque low lines and simplicity of design kept me from seeing how big it was until I was inside. Through the inner glass door of the vestibule I could see the fifty-yard swimming-pool contained in its U-shaped wings. The ocean end opened on bright blue space.

The door was locked. The only human being in sight was a black boy bisected by narrow white trunks. He was sweeping the floor of the pool with a long-handled underwater vacuum. I tapped on the door with a coin.

After a while he heard me and came trotting. His dark, intelligent eyes surveying me through the glass seemed to divide the world into two groups: the rich, and the not so rich. I qualified for the second group, it seemed. He said when he opened the door: “If you’re selling, mister, the timing could be better. This is the off-season, anyway, and Mr. Bassett’s in a rotten mood. He just got through chopping me out. It isn’t my fault they threw the tropical fish in the swimming-pool.”

Читать дальше