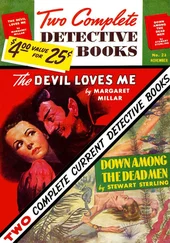

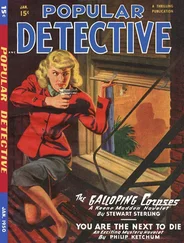

“Kindly Omit Flowers” was first published in the March 1942 issue of Black Mask.

The Herald of Happiness was the answer to an old maid’s prayer. To its clarion call hearkend one ecstatic victim after another — till Sergeant Helen Dixon of the Policewomen’s Bureau was summoned by the siren tones to keep a blind date with death.

Chapter One

A Gruesome Exhibit

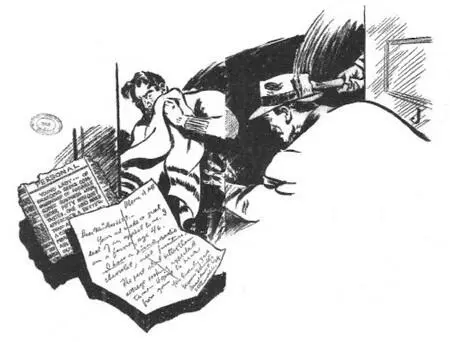

Lieutenant Teccard rocked back in his swivel chair. His fingers gripped the shiny oak arm-pieces tightly. It was an instinctive movement to get as far away as possible from the thing on his desk. Ordinarily, his office in the headquarters building seemed large enough. Now, suddenly, it was oppressively small and close. He kept his eyes away from the long, glass tray on the flat-top, as he reached for the phone.

“O.K. for Sergeant Dixon.”

The woman who came in wouldn’t have been noticed in the average Manhattan lunch-hour crowd. She was pretty, but she hadn’t worked hard at it. A man might not have paid particular attention to her as he passed her on the street, unless he happened to meet her glance. Her eyes were gray and curiously calm — as if they had seen a lot they hadn’t found amusing.

She wrinkled up her nose. “My God, Jerry! A man can live without food for three weeks and without water for three days! But you can’t last three minutes without air!”

Jerry Teccard shoved his brown felt back off a harassed forehead. “Light a cigarette if it gets you, Helen.” He indicated the roll of checkered oilcloth resting in the photographic tray. “You don’t have to turn yourself inside out, gandering at this. You can take the medical examiner’s word for it.”

Acting Detective-sergeant Helen Dixon, second grade, regarded him grimly.

“After that year I put in at the Forty-seventh Street station, it’ll take something to turn m stomach,” she declared.

He lifted one corner of the oilcloth cylinder. “What’s left of a woman’s thigh. After the wharf rats worked on it awhile.”

Her lips compressed a little, but none of the color left her face.

“Where’d it come in?”

“Twenty-third precinct. East Hundred and Fourth.” He consulted a report sheet. “James Boyle, probationer, found a child trying to salvage the oilcloth that had been tied around it with some string. Boyle’s beat takes him along the Harlem docks, foot of Ninety-eighth. This thing was on the tide flat at the side of the Ninety-eighth Street pier.”

“When was this, Jerry?”

“This a.m. Quarter past ten. Doc says it’s been lying there, or under the head of the pier, more’n a week. Some pupae of flies in the end of the bone. Eggs must’ve been laid seven, eight days ago, anyway.”

Helen Dixon bent over the tray. She didn’t peer at the discolored bone, her finger pointed to brown shreds of fiber which clung to the outside of the oilcloth.

“You said it was tied with string?” she asked.

Teccard pointed to a soggy tangle of frazzled gray in one corner of the tray. “Was. Doesn’t mean a thing, though. Million yards of that stuff used every day.”

“But these look like rope strands to me.”

He squinted at them. “I noticed those. I’m going to send ’em up to the lab, for a microscopic. But the reason I sent for you—”

“You figure this might be one of the Happiness cases?” She moved past his chair to the window, opened it from the bottom a few inches, stood staring down into Centre Street.

“There’s better than an even chance. That’s why I asked the Policewomen’s Bureau to send you up here. I know you’ve been plugging like hell on that assignment. If Crim. Ident. can help, maybe you and I can work together on it. Like old times, when you were playing Big Sister to the floozies we picked up on Sixth Avenue.” He swung around toward her. “My office wouldn’t want any credit.”

She touched his shoulder lightly for an instant, spoke without turning around.

“Damn the credit! If I could only break the case. I’ve been running around in circles for three weeks, hoping it’s just another flock of old maids forgetting about friends and families because wedding bells are still ringing in their ears. But if this,” she inclined her head toward the tray, “is one of them, it means the very nastiest kind of murder.”

Teccard nodded. “Never knew a suicide to cut off her leg. It’s pretty obvious.”

“Any special reason to think she was one of this matrimonial agency’s customers?”

He lifted his chin, ran a finger around under his collar uncomfortably. “Remember what you said that day we had lunch at the Savarin? About the kind of heels who have to find their females through an ad? Especially when they pick on dames who’ve had the lousy luck to be disfigured or crippled?”

Her voice was bitter. “I’m not likely to forget. Every one of those five appeals for inquiry come from friends or relatives of women who have some physical disability — or some facial blemish that would put them at a disadvantage in the national pastime of husband-hunting. Of course those poor lonely lambs could be led to the slaughter, by some unscrupulous devil who flattered them and promised them... whatever he promised.”

Teccard fiddled with pipe and pouch. “Well, that thigh bone was broken. In two places. While she was living, I mean.”

Helen Dixon turned, perched on the window sill. “The left leg?”

“Yair. Wasn’t there one of those dames...?”

“Ruby Belle Lansing.” The sergeant eyed the oilcloth with repugnance. “Spinster. Thirty-six. Grade-school teacher in Tannersville. Hip broken in automobile accident, October 1939. Double fracture, set at Catskill Memorial Hospital. Entered into correspondence with the Herald of Happiness in August 1941. Came to New York, October sixth, after being introduced, by mail, to Philip Stanton, then of 4760 Madison Avenue, this city.”

The lieutenant consulted his report sheet. “Length of femur, 18.1 inches. Let’s see — factor for women is three and six-tenths. About sixty-five inches tall. Would this Lansing—”

“She was just five feet, five, Jerry. By the Tannersville Board of Education records. What must have been more important to Stanton, Ruby Belle had a little more than two thousand dollars in the savings bank at Phoenicia. Three days after her arrival, she had this deposit transferred to the Emigrant Bank here. On October tenth, the next day, it was withdrawn, except for ten dollars. Since then, there hasn’t been a trace of her. Or of Stanton!”

“Any description of him?”

Helen shrugged. “Nothing to count. He never went to Tannersville. Her uncle — the one who asked us for a check-up — said he saw a snapshot of Stanton. But all he remembers is, the fellow was good-looking and had a mustache.”

“That’s a great big help!” Teccard called for a policeman to take the thigh-bone back to the morgue. “What about the people where Stanton lived?”

“A rooming house. Man who runs it’s nearly blind. Stanton didn’t seem to use the room much, anyway. Half the time the bed wasn’t disturbed. Best I could get was, he was kind of dark.”

“Ah! Send out an all-borough to pick up dark guys with mustaches! And reserve Central Park to hold ’em in! Yair! How about the other four who’re missing? Same skunk, each time?”

Helen bent over the oilcloth, peered at the brown fiber again. “I wish I could remember what that stuff makes me think of. About the men in the other cases — I’m up against one of those things, Jerry. The disappearances were strangely similar. In every instance, the man resided in New York. The woman involved always lived in some small town, upstate. And every time the man sent the woman a ticket to come to the big city. What’s more, flowers were invariably sent. Can you tie that? A bouquet for the unseen bride! Also, every one of the five dropped out of sight within three or four days — after sending for their home-town funds.”

Читать дальше