“Joseph Stackett.”

“Stackett?”

The light flashed on his face again. “How wonderful! Do you remember the Exeter Assizes? The old woman you killed with a hammer? I defended you!”

Joe’s eyes were wide open. He stared past the light at the dim grey thing that was a face.

“Mr. Lenton?” he said hoarsely. “Good God, sir!”

“You murdered her in cold blood for a few paltry shillings, and you would have been dead now, Stackett, if I hadn’t found a flaw in the evidence. You expected to die, didn’t you? You remember how we used to talk in Exeter Gaol about the trap that would not work when they tried to hang a murderer, and the ghoulish satisfaction you had that you would stand on the same trap?”

Joe Stackett grinned uncomfortably.

“And I meant it, sir,” he said, “but you can’t try a man twice—”

Then his eyes dropped to the figure at his feet, the dapper little man with a black moustache, with a red hole in his temple.

Lenton leant over the dead man, took out a pocket-case from the inside of the jacket and at his leisure detached ten notes.

“Put these in your pocket.”

He obeyed, wondering what service would be required of him, wondered more why the pocket-book with its precious notes was returned to the dead man’s pocket.

Lenton looked back along the road. Snow was falling now, real snow. It came down in small particles, falling so thickly that it seemed that a fog lay on the land.

“You fit into this perfectly... a man unfit to live. There is fate in this meeting.”

“I don’t know what you mean by fate.”

Joe Stackett grew bold: he had to deal with a lawyer and a gentleman who, in a criminal sense, was his inferior. The money obviously had been given to him to keep his mouth shut.

“What have you been doing, Mr. Lenton? That’s bad, ain’t it? This fellow’s dead and—”

He must have seen the pencil of flame that came from the other’s hand. He could have felt nothing, for he was dead before he sprawled over the body on the ground.

Mr. Archibald Lenton examined the revolver by the light of his lamp, opened the breech and closed it again. Stooping, he laid it near the hand of the little man with the black moustache and, lifting the body of Joe Stackett, he dragged it toward the car and let it drop. Bending down, he clasped the still warm hands about the butt of another pistol. Then, at his leisure, he took the bicycle from the interior of the car and carried it back to the road. It was already white and fine snow was falling in sheets.

Mr. Lenton went on and reached his home two hours later, when the bells of the local Anglo-Catholic church were ringing musically.

There was a cable waiting for him from his wife:

A Happy Christmas to you, darling .

He was ridiculously pleased that she had remembered to send the wire — he was very fond of his wife.

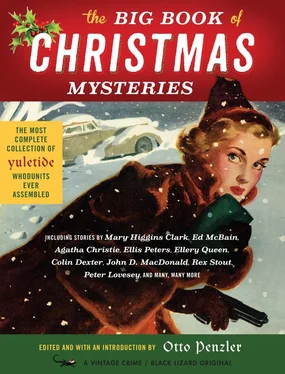

A Christmas Tragedy

Agatha Christie

It will surprise no one to say that Agatha Christie is the most popular writer of detective fiction who ever lived (her sales in all languages are reported to have surpassed four billion copies). Her remarkably proficient first book, The Mysterious Affair at Styles (1920), is generally and rightfully given credit as the landmark volume that initiated what has been called the Golden Age of mystery fiction. This era, bracketed by the two World Wars, saw the rise of the fair play puzzle story and the series detective, whether an official member of the police department, a private detective, or an amateur sleuth, and it was Christie who towered above all others, outselling, outproducing, and outliving the rest. “A Christmas Tragedy” was first collected in The Thirteen Problems (London, Collins, 1932).

• • •

“I have a complaint to make,” said Sir Henry Clithering.

His eyes twinkled gently as he looked round at the assembled company. Colonel Bantry, his legs stretched out, was frowning at the mantelpiece as though it were a delinquent soldier on parade, his wife was surreptitiously glancing at a catalogue of bulbs which had come by the late post, Dr. Lloyd was gazing with frank admiration at Jane Helier, and that beautiful young actress herself was thoughtfully regarding her pink polished nails. Only that elderly spinster lady, Miss Marple, was sitting bolt upright, and her faded blue eyes met Sir Henry’s with an answering twinkle.

“A complaint?” she murmured.

“A very serious complaint. We are a company of six, three representatives of each sex, and I protest on behalf of the down-trodden males. We have had three stories told tonight — and told by the three men! I protest that the ladies have not done their fair share.”

“Oh!” said Mrs. Bantry with indignation. “I’m sure we have. We’ve listened with the most intelligent appreciation. We’ve displayed the true womanly attitude — not wishing to thrust ourselves into the limelight!”

“It’s an excellent excuse,” said Sir Henry; “but it won’t do. And there’s a very good precedent in the Arabian Nights! So, forward, Scheherazade.”

“Meaning me?” said Mrs. Bantry. “But I don’t know anything to tell. I’ve never been surrounded by blood or mystery.”

“I don’t absolutely insist upon blood,” said Sir Henry. “But I’m sure one of you three ladies has got a pet mystery. Come now, Miss Marple — the ‘Curious Coincidence of the Charwoman’ or the ‘Mystery of the Mothers’ Meeting.’ Don’t disappoint me in St. Mary Mead.”

Miss Marple shook her head.

“Nothing that would interest you, Sir Henry. We have our little mysteries, of course — there was that gill of picked shrimps that disappeared so incomprehensibly; but that wouldn’t interest you because it all turned out to be so trivial, though throwing a considerable light on human nature.”

“You have taught me to dote on human nature,” said Sir Henry solemnly.

“What about you, Miss Helier?” asked Colonel Bantry. “You must have had some interesting experiences.”

“Yes, indeed,” said Dr. Lloyd.

“Me?” said Jane. “You mean — you want me to tell you something that happened to me?”

“Or to one of your friends,” amended Sir Henry.

“Oh!” said Jane vaguely. “I don’t think anything has ever happened to me — I mean not that kind of thing. Flowers, of course, and queer messages — but that’s just men, isn’t it? I don’t think” — she paused and appeared lost in thought.

“I see we shall have to have that epic of the shrimps,” said Sir Henry. “Now then, Miss Marple.”

“You’re so fond of your joke, Sir Henry. The shrimps are only nonsense; but now I come to think of it, I do remember one incident — at least not exactly an incident, something very much more serious — a tragedy. And I was, in a way, mixed up in it; and for what I did, I have never had any regrets — no, no regrets at all. But it didn’t happen in St. Mary Mead.”

“That disappoints me,” said Sir Henry. “But I will endeavour to bear up. I knew we should not rely upon you in vain.”

He settled himself in the attitude of a listener. Miss Marple grew slightly pink.

“I hope I shall be able to tell it properly,” she said anxiously. “I fear I am very inclined to become rambling . One wanders from the point — altogether without knowing that one is doing so. And it is so hard to remember each fact in its proper order. You must all bear with me if I tell my story badly. It happened a very long time ago now.

“As I say it was not connected with St. Mary Mead. As a matter of fact, it had to do with a Hydro—”

“Do you mean a seaplane?” asked Jane with wide eyes.

Читать дальше