There are almost 50 pages of notes for this title, mainly in Notebook 61. Called by Christie’s husband, Sir Max Mallowan, ‘the most beautiful play’ she ever wrote, it is based on the real-life Pharoah Akhnaton of Egypt in 1375 BC Although written in 1937 it was not published until 1973, with a blurb written by Agatha Christie herself. Shortly after its completion Christie sent it to the actor (later Sir) John Gielgud. His reply, which she kept, expressed his admiration for the play while declining to become involved in a production. In fact Akhnaton was never professionally produced, but it was seen in the Westcliff Agatha Christie Theatre Festival in 2001; the one-off presentation used a minimum of setting and props and was, in essence, an elaborate reading.

Although by no means a typical Agatha Christie play, it does contain Christie-like elements—there is a death by poisoning, masterminded by an unsuspected villain using an innocent party.

There are 40 pages of notes for this play. These include extensive background material as well as sketches for the play itself. The very first page of notes begins with a cast list (in the published version Mutnezmet, Nefertiti’s sister, has become Nezzemut), and this is followed by a sketch of the opening scene:

Queen Tyi

Horemheb

Eye

Nefertiti

Mutnezmet

Tutankhamun

The father of Tyi

The mother of Tyi

The High Priest of Amon

The High Priest of Re

A Priest of Ptah

Act I Scene I

Amenhotep the Magnificent is near to death—the king of Mitanni sends the image of Ishtar of Niniveh to Egypt (second time such a procedure happened) in hopes that the Goddess might exorcise the evil spirits which were causing the King’s infirmity. The Goddess passes through. Horemheb talks with the father and mother of Tyi talk together. The High Priest of Ammon talks to Horemheb—on evils of foreign marriage—Queen Tyi appears with her son.—

The early pages of Notebook 61 show seven scenes for Act I, four for Act II and two for Act III. A redrafting ten pages later brings it closer to the published version, which has three scenes each for the first two Acts and four for the third with an Epilogue. The notes show this Epilogue as the last scene of the play.

In between the drafts there are notes on

Indulgences—A verdict of acquittal sold by Scribes—pardoned names inserted in the blanks.

Heart scarab—‘O my heart rise not up against me as a witness’

Gold collars as gifts—

The book From Fetish to God by Budge is also mentioned on the very first page and there are page references to it throughout the notes. This research is similar to that undertaken by Christie for Death Comes as the End from books loaned to her by Stephen Glanville, the dedicatee (see Chapter 7):

Visit by Tyi in 12th year of A’s reign—description of clothes P.155

Tribute?—A scene showing it being brought’ P.151

Description of Palace for scene P.138

One of the earliest quotations, presumably from this book, is reproduced with minor variations to form almost the closing lines of the play. The last traces of Akhnaton are erased, soon to be replaced by ‘the divine Amon, King of Gods’:

How bountiful are the possessions of him who knows the gifts of that God (Amon). Wise is he who knows him. Favoured is he who serves him, there is protection for him who follows him.

Exhibit F: The House of Dreams: Unused Ideas

‘Unless I get a rough sketch of my idea down, it will go’

Mrs McGinty’s Dead, Chapter 24

SOLUTIONS REVEALED

Four-Fifty from Paddington • ‘Jewel Robbery at the Grand Metropolitan’ • ‘Miss Marple Tells a Story’

There is a story, possibly apocryphal, that detective novelist Nicholas Blake (in real life the Poet Laureate Cecil Day Lewis) offered to buy some plot ideas from Christie but she replied that she intended using them all herself. The Notebooks are littered with such ideas and what follows are some of those that never got further than the page on which they appeared. Some haunted her—the non-identical twins, the chambermaid, the arty friends—as they appeared again and again.

Twins—point is not identical—Twins identical—one killed in railway smash?

Identical twins—claimant assumes identity of sister (killed in railway smash) rich widow

These are just two of the ten versions of the ‘twins’ idea that litter the Notebooks. A railway smash and a false identity are minor features of Murder in Mesopotamia. Twin sisters also feature in Elephants Can Remember and on a more lighthearted note, twins are the solution to one of Tommy and Tuppence’s Partners in Crime cases.

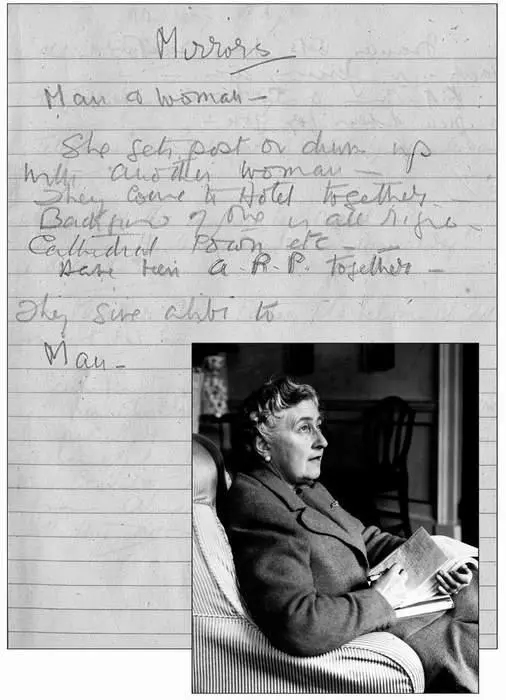

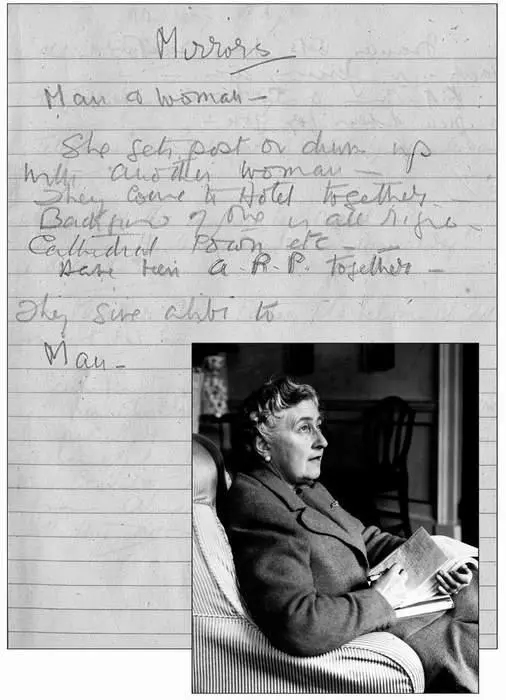

Mirrors

Man or woman—she gets post or chums up with another woman—they come to hotel together.

Background of one is all right—cathedral town etc. Have been in A.R.P. together—they give alibi to man

The heading ‘Mirrors’ confirms what a diffuse history They Do it with Mirrors had. The only tenuous connection to that novel is the idea of giving an alibi to someone.

Nitro benzene—point is—it sinks to bottom of glass—woman takes sip from it—then gives it to husband

Camphor in capsule

Murder by lipstick—lip burnt first—cigarette given wrong end first

Strychnine or drug absorbed through skin

Influenza depression virus—Stolen? Cabinet Minister?

Lanolin poison? Strychnine? The poison that makes everything yellow (applied to dress—very misleading as another girl had yellow dress (1931)

Lanoline rubbed into skin

Despite its heading, this page from Notebook 19 has no connection with any ‘Mirrors’ title. It is the page open on Christie’s lap in this 1946 photograph.

These are just a few of the ideas using various forms of poison, Christie’s favourite method of despatch throughout her career. ‘Murder by lipstick’ is particularly imaginative.

Chambermaid in hotel accomplice of man—evidence always accepted and clinches case

Chambermaid story—a hotel—Torquay? Riviera? Spain? Majorca? English better

The chambermaid idea, of which the above are just two examples, appears ten times in the Notebooks. Evidently the idea of a dishonest chambermaid was one that held possibilities for Christie as she utilised it in both ‘The Jewel Robbery at the Grand Metropolitan’ and ‘Miss Marple Tells a Story’. But neither of those fits the plot device of any of the above. The second one is vague enough to fit anything.

Legless man—sometimes tall—sometimes short

The ‘legless man’ motif is another idea that appears in ten Notebooks although nothing was ever made of it. The idea behind this device was that such a person could alter his appearance very dramatically, thereby making identification difficult. Christie’s fellow detective novelist John Dickson Carr used this plot device definitively in his 1938 novel The Crooked Hinge.

Stabbed through eye with hat pin

This very gruesome idea is untypical of Christie, its attraction probably the difficulty of spotting the means of death. It also appears in three other Notebooks.

Isotope idea—Carbon 14—hypodermic injection (for typhoid?) normal procedure. He (?) is going abroad appointment—with local doctor—his place is taken by impostor who gives so-called typhoid injection.

This idea, inspired by a visit to a laboratory during a US visit in the 1960s, has strong echoes of One, Two, Buckle my Shoe in the impersonation of a doctor in order to poison a patient.

Читать дальше

Конец ознакомительного отрывка

Купить книгу