A man’s wife hangs herself—he cuts her down in time. Really man is preparing the way for her suicide…Does this tie in with what doctor or other officer remembers of another case—same man

Story about—woman hanged herself—husband cut her down in time—hushed up

One fact strikingly revealed by the Notebooks is how different a story A Caribbean Mystery could have been. In early drafts in Notebook 3 we see the germ of a bizarre idea, not pursued, which is elaborated in Notebook 18. Note also the early possibility of including Hercule Poirot. I can only speculate that Poirot was dropped in favour of Miss Marple as Christie, now as elderly a lady as her creation, had spent a happy holiday in the Caribbean:

(Happy idea) West Indian book—Miss M? Poirot

Girl crippled by polio—has given up her young man—goes out to where they were going on their honeymoon—she has nurse with her—a rather doubtful character—girl kills anyone who is happy

West Indies

Miss Marple and possibly Jean Brent—Polio victim and a hospital nurse Doran Watson (Miss? Mrs.?)

Could start with the girl—Jean—crippled—tells fiancé she must give him up—he protests—everyone applauds her—then given a trip because she wishes she could get away. Raymond must perhaps make an arrangement with Mrs. Watson who is going with an old Mr. Van Dieman (rich)—(to give him massage every day?)…

If a warped Jean who hates to hear other people’s happiness is the murderer—how does she bring it about.

Poison? Narcotic? Tranquillisers? Substitution of same Pep pills—What drug

Combine Polio Jean—(or car accident) sacrifice with frog faced Major (West Indies)

Three consecutive pages in Notebook 3 contain three important elements of A Caribbean Mystery:

Book about Cretan Bull idea—insanity induced by doses of Belladonna.

2 pairs husband and wife—B and E apparently devoted—actually B and G (Georgina) have had an affair for years—Brian, G’s husband doesn’t know? Really it is a different husband and wife—husband is a wife killer. Old ‘frog’ Major knows—has seen him before—he is killed

And it is in Notebook 18 that we get the main source of misdirection (even though it is mentioned frequently)—the idea of the glass eye:

A different story by Major P—his glass eye rests on ? (1) ? (2) but really on Jean and Nurse Boscombe

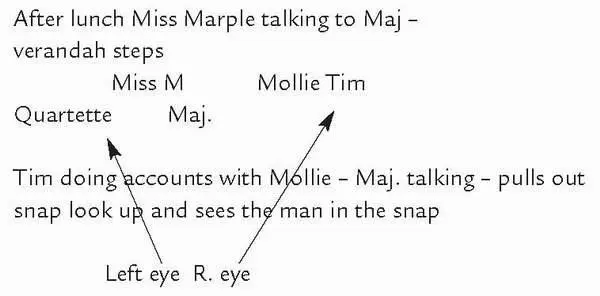

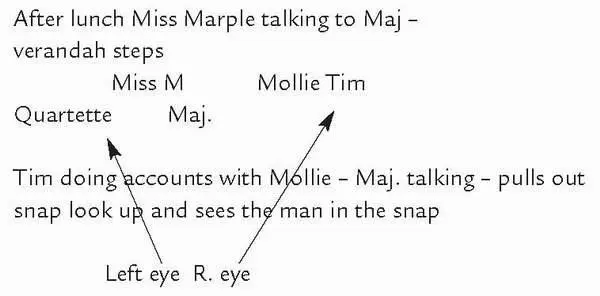

Interestingly, in the original typescript at the end of Chapter 23 and after the ‘Evil Eye…Eye…Eye’ clue, there is an extra sentence—‘ Miss Marple gasped. ’ This may have been considered too daring and does not appear in the published version. And in Notebook 23 we get a rough sketch, literally, of the all-important scene, with the Major looking over Miss Marple’s shoulder. Here Christie draws, probably for her own clarification, the physical set-up as Miss Marple listens to the Major’s story and misinterprets his gaze:

After lunch Miss Marple talking to Maj—verandah steps

Notebook 58 is still considering very basic character setting and a slightly different version of the story told by Major Palgrave. Here, the CID man who investigated the crimes tells the story directly to Miss Marple. At this stage in the planning there is no mention of the hotel owners—just the quartet. But there was to be a Christiean twist, not adopted for the novel, even with this limited field of suspects.

Carribean [sic] Mystery

A quartet [of] friends

Mr and Mrs R. Rupert and Emily—English—friends of many years standing—one pair app[ear] very devoted. One daywife confides they never speak to each other in private—husband (to girl) says wonderful life together—which is lying?

The CID man is in County district in England—man’s phone broken down—he walks into town—(car at garage) for doctor—they get back—wife is dead—heart?—man terribly upset—it worries CID man—remembers man—has seen him before—remembers—in France—and his wife had died—same thing in Canada—then marries an American woman—comes to Tobago—CID man found dead

But is it really the woman—The dog it was that died

The wrong man or wrong woman dies—of heart trouble so that you suspect the wrong pair—really Mrs Rupert is the one with her fads and illnesses—she and chap are having an affair

Finally, we can see the amount of thought that went into the Major and his story, elements of which appear in three Notebooks:

Problem of Major P

Points Why did Major not recognise his murderer before?

No new comers to the island—Edward, Greg, Van D Jackson all known to him

Answer by Miss M?—Major had not seen the man himself—this was a story told him—he had only glanced at snap—then kept it as a curiosity—he takes it out preparatory to showing it to her looks at it—looks up, seeing suddenly the man in the photograph—hastily stuffs it back again

Possibilities (1) Major had several murderer stories that he had picked up in course of travel

(2) Could Miss M—(or Esther) have misunderstood

(3) (Not supported!) Esther lied—why?

The murderer story is different—could be either a man or a woman.

Does Kelly tell Miss M—how Palgrave told him a story this indicates that it was a woman

Miss M with Jenny in West Indies

The frog faced Major—his gossip—glass eye—appears to be looking different direction from what he really is—3 husband and wives applicable—Chuck and Patty (affair?)—Greg and Sarah Evelyn

Once more, we can see how the fertility of Christie’s imagination might have created a very different novel from the one we have.

9

In a Glass Darkly:

The Unknown Christie

‘…that is to say UN Owen. Or by a slight stretch of fancy: UNKNOWN’

Ten Little Niggers, Chapter 3

Apart from Agatha Christie’s enormous known output there is also a number of works that are largely unknown, except to the most ardent fans. These titles are all scripts, either for the stage or radio, and have all been either performed or published. And all of these titles feature in the Notebooks, some of them to a large degree.

Agatha Christie is still the only crime novelist to have had an equally successful career as a playwright. Indeed, arguably the greatest monument to her success is a play, The Mousetrap. The majority of her plays are well known but there are still a few surprises.

Akhnaton is a non-crime script from 1937 based on the reallife Pharoah Akhnaton of Egypt. The little-known Rule of Three contains three utterly contrasting one-act plays, Christie’s only venture into this form. And the final title in this chapter is the last play that she wrote, Fiddlers Three. Neither play received encouraging reviews, although both contain much interesting material.

For future consideration are the totally unknown radio plays Personal Call and Butter in a Lordly Dish, and Chimneys. The latter is her own adaptation, and reworking with a new villain, of the 1925 novel The Secret of Chimneys; the former two original plays written directly for radio. None of the three is currently available in any form.

Rule of Three 20 December 1962

Over 40 years after her career began Christie was still experimenting when Rule of Three was first presented at the Duchess Theatre, London. Reviews were not good however and apart from Fiddlers Three, which never had a West End run, it lowered the curtain on her golden age of theatre. It is now an unknown Christie because it has seldom been staged since. But Rule of Three shows that, even after a lifetime of hoodwinking her audience, she still had the ability to surprise and entertain. Each of the three plays represents a different aspect of Christie and, moreover, aspects that are very unexpected and atypical. Of the three plays, Afternoon at the Seaside is the most unlikely play ever to have come from the pen of Agatha Christie; The Rats is not a whodunit but a claustrophobic will-they-get-away-with-it; while The Patient is the essence of Christie.

Читать дальше

Конец ознакомительного отрывка

Купить книгу