The coroner looked up at Edwin. ‘How many were sleeping here last night?’

‘We only had three besides him,’ quavered the old man. ‘Apart from that drunken sot in the corner.’

De Wolfe loped across the loft and shook the man awake, but could get no sense out of him, as he was still totally befuddled.

‘Who were the other three?’ he demanded, frustrated at the lack of witnesses. Edwin shrugged and Nesta answered from where she stood on the ladder, halfway into the loft.

‘They were travellers, who went on their way soon after dawn. They took pallets in the first row just here, so can’t have noticed this man lying dead over there in the darkness.’

‘Somebody must have come up here to kill him, so maybe it was them,’ reasoned Gwyn.

Nesta shrugged her shapely shoulders. ‘We were even busier than usual late last night. People come and go all the time. I can’t watch every move they make.’

‘He doesn’t look as if he had anything worth being robbed for,’ objected Gwyn, prodding the corpse with his foot.

‘His scrip looks empty, but you’d better make sure,’ ordered de Wolfe, indicating the frayed leather purse on the man’s belt.

Gwyn pulled it off and squeezed it, feeling nothing inside. He opened the flap and upended it over his palm. ‘That’s odd!’ he boomed. ‘Let’s have that light a bit nearer, Edwin.’

As they stooped over the lantern, they could see small flecks glistening in its light.

‘Shreds of gold leaf, just like we found on that fellow robbed at Clyst St Mary! Bloody strange, that!’ observed Gwyn.

De Wolfe rubbed at his stubble thoughtfully, but could make no sense of the coincidence. He decided to leave his inquest until the afternoon, giving Gwyn time to round up as many of the previous night’s patrons as he could find, to form a jury. Meanwhile, they adjourned down to the taproom for some ale and food, while they discussed the matter. As soon as Nesta’s maids had scurried in with bread, cold meat and cheese, and Edwin had brought brimming pots of the best brew, they sat around a table and tried to make sense of this violent death. Thomas seemed very pensive as he sat picking at his breakfast.

‘I’ve been thinking about what the other dead man said before he passed away,’ he offered timidly.

Though Gwyn was playfully scornful of the little clerk, John de Wolfe had learned to respect the ex-priest’s learning and intelligence.

‘What’s going through that devious mind of yours, Thomas?’ he asked encouragingly.

‘This gold leaf-that must surely link them, it’s not a common thing to find in poor men’s pouches. And gold leaf is usually applied to valuable or sacred objects.’

‘How’s that connected with whatever that robbed fellow said in Clyst?’ asked the sharp-witted Nesta.

‘It comes back to me now-the old man in Clyst said the victim had uttered the words “Barzak” and “Glastonbury”.’

‘If he was walking northward through that village, he may well have been making for Glastonbury, so what’s the mystery?’ grunted Gwyn.

‘It’s the oldest abbey in England-Joseph of Arimathaea and perhaps even the Lord Jesus himself may have visited there,’ said Thomas, crossing himself devoutly. ‘But it’s the other word he uttered that intrigues me-Barzak!’

‘What the hell’s a barzak?’ growled the big Cornishman, determined to deflate his little friend.

‘Not what, but who?’ retorted Thomas. ‘I recollect the legend now, it’s been told around our abbeys and cathedrals for many years. It’s a curse, which again the old man in Clyst mentioned.’

Nesta, Edwin and even Gwyn were now intrigued, but de Wolfe was his usual impatient self.

‘Well, get on with it, Thomas! What are you trying to say?’

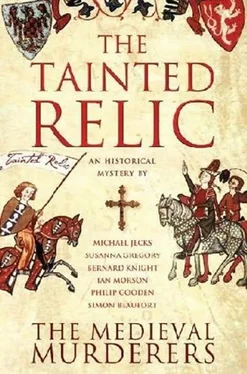

‘The Templars brought this story back long ago, of a tainted relic from the Holy City.’ He crossed himself yet again. ‘It seems that a fragment of the True Cross was cursed by a custodian called Barzak and anyone handling it died a violent death as soon as it left his possession. The relic has been virtually hidden away somewhere in France for many years-I seem to have heard it was in Fontrevault, where old King Henry’s buried. It was useless as an attraction for pilgrims, as they learned to shun it.’

The coroner pondered this for a moment, as he supped the last of his ale. ‘So why should this thing turn up in Devon?’ he asked dubiously.

Thomas shrugged his humped shoulder. ‘Perhaps the man in Clyst had brought it from France-he could have been coming from the port of Topsham, if he was on his way to Glastonbury.’

‘Sounds bloody far fetched to me!’ mumbled Gwyn through a mouthful of bread and cheese.

De Wolfe stood up and brushed crumbs from his long grey tunic.

‘It’s all we’ve got to go on so far. Thomas, you’re the one with the religious connections, so go around and see if you can find any rumours about a relic. And you, Gwyn, round up as many men who were drinking in here last night as you can and get them down here before vesper bell this afternoon. I’ll go and tell our dear sheriff we’ve had a murder in the city.’

The coroner’s brother-in-law, Sir Richard de Revelle, was busy with his chief clerk in his chamber in the keep of Rougemont when John arrived. He sat at a table, poring over parchments that listed tax collections, ready for the following week’s visit to the Exchequer at Winchester. More concerned with money than justice, the sheriff was supremely uninterested in the death of a lodger in an alehouse, until he heard that the man was a priest. At this news, de Revelle sat back and stared at de Wolfe.

‘A priest? Staying in that common tavern, run by that Welsh whore?’

John resisted the temptation to punch him on the nose, as he had suffered this particular provocation many times before.

‘My officer and clerk are about the town now, trying to find out more about him,’ he replied stonily. ‘There may be a connection with the murder of a chapman yesterday-probably by outlaws.’

De Revelle was more concerned about the man being a cleric, not out of any particular concern for the welfare of priests, but because he was a political ally of Bishop Henry Marshal in their covert campaign to put Prince John on the throne in place of Richard the Lionheart. De Revelle was always on the lookout for any opportunity to further ingratiate himself with the prelate, so he felt it might be worth stirring himself to catch the killer, if it raised his stock with the bishop. He demanded to know the details of the crime and John explained the circumstances of both deaths, but held back Thomas’s suggestion about the cursed relic.

Richard leant back in his chair and stroked his neatly pointed beard thoughtfully. He was a small, dapper man, with a foxy face. Fond of showy garments, today he wore a bright green tunic with yellow embroidery around neck and hem, with a cloak of fine brown wool trimmed with squirrel fur thrown over his shoulders against the chill of the cold, dank chamber.

‘A gang of outlaws could hardly have cut the man’s throat in the upstairs of a city alehouse-even though that Bush is a den of iniquity!’ he sneered, determined to taunt his sister’s husband with reminders of his infidelity. ‘Far more likely that your doxy turned a blind eye to some local robber who preys on her guests.’

Once again, John refused to rise to the bait and suggested that a squad of soldiers should be sent to clear the outlaws from the woods around Clyst St Mary. De Revelle dismissed this idea with a wave of his beringed hand.

‘A waste of time! Every bit of forest in Devon is crawling with these outcasts. Trying to find them is like looking for a needle in a haystack. But I want to catch the killer of this priest, for the bishop will be on my neck as soon as he hears about it.’

Читать дальше