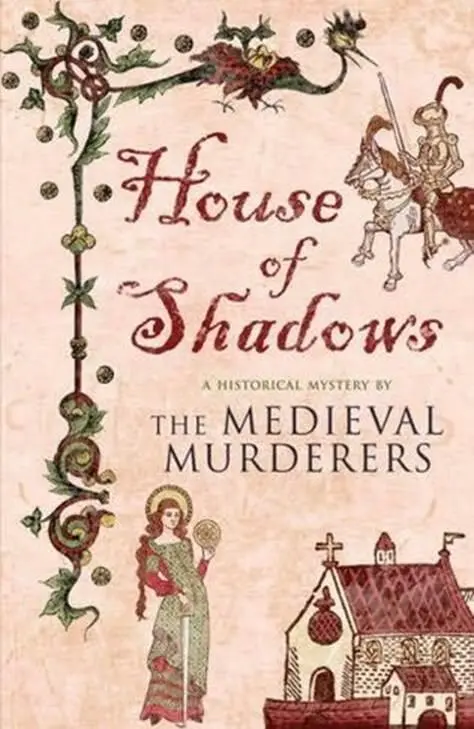

The Medieval Murderers

House of Shadows

The third book in the Medieval Murderers series, 2007

Prologue– In which Bernard Knight lays the foundation for the ghoulish tales that follow.

Act One– In which Bernard Knight tells how Crowner John arrives at the priory of Bermondsey to investigate murder most foul.

Act Two– In which Ian Morson’s William Falconer uncovers dark deeds during an eclipse of the moon.

Act Three– In which Michael Jecks’ Keeper Sir Baldwin and Bailiff Puttock uncovers a treasonous plot.

Act Four– In which Philip Gooden relates how the poet Chaucer becomes embroiled in the priory’s dark history.

Act Five– In which Susanna Gregory’s Thomas Chaloner, spy for the Lord Chancellor of England, avenges a violent death.

Epilogue– In which Bernard Knight exposes the final secret.

HISTORICAL NOTE

Bermondsey lies on the south bank of the Thames, near where Tower Bridge now stands. A priory was established there as early as 1089 and became one of the richest in England due to numerous gifts of land and money. Originally founded by four Cluniac monks from France, who built on ground donated by a rich London merchant, the priory became a Benedictine abbey in 1399, surviving until Henry VIII dissolved all monasteries in the sixteenth century. It was then built over repeatedly, though the gatehouse survived until the nineteenth century.

Though this famous monastery had a very real existence for hundreds of years, the stories in this book are works of fiction. In the early years of the twenty-first century, extensive excavations were carried out by archaeologists, prior to a huge commerical complex being built over the site. The events described in the Epilogue are similarly fictitious.

December 1114

Grey mist, like wet smoke, slowly rolled over the wall of the priory, seeping in from across the marshes that lined the Thames. Together with the winter twilight, the fog made it almost dark, though the bell for vespers was only now sounding, its doleful tone muffled in the moist air.

A small procession was slowly crossing the outer courtyard towards the west front of the church, the black Cluniac habits adding to the already sombre atmosphere. Of the dozen hooded figures walking in pairs, three were openly sobbing, and the expressions on the remaining grim faces were set in barely contained emotion. Behind them in the inner courtyard was a closed door, which until today had been merely the entrance to the cellarer’s storeroom but which now concealed a dreadful secret.

As their sandalled feet padded across the damp earth towards the steps of the new church of St Saviour’s, the monks’ faces were lit by the flickering yellow light of two pitch-brands set in iron rings on each side of the west door. The light fell first on the prior, Peter de Charité, who at fifty was a strong, hard-faced disciplinarian. The monk alongside him and the two immediately behind were Richard, Osbert and Umbold, who had accompanied him from France fifteen years before, sent to establish a new daughter house of Cluny in this fog-ridden swamp that was Bermondsey.

Since then, eight more monks had joined them as the priory flourished, nurtured by gifts of land from various benefactors. There had been nine, and therein lay the cause of their present misery.

‘King Henry must never hear the truth of this,’ murmured Osbert, his teeth chattering from fright rather than the cold.

‘But how are we going to keep it from him?’ keened Richard, who was too old to have teeth to chatter.

‘Be quiet, brothers!’ snapped Peter. ‘In fact, keeping very quiet is what we must all do.’

The four founders were sitting around the fireplace in the prior’s chamber, the other monks having been left in the church to pray for absolution until it was time for the evening meal. Umbold, a fat man of middle age, had no tonsure like the others, as he was completely bald.

‘Count Eustace will be here after Epiphany to confirm the grant,’ he moaned. ‘What are we to tell him?’

There was silence as they all considered this yet again. The problem had dominated their minds ever since the catastrophe had fallen on them three days ago. Earlier that year, Mary, the wife of Eustace, Count of Boulogne, and sister of Queen Maud, had granted the manor and advowson of Kingweston to the priory. Recently, Eustace had declared his intention of visiting them personally to confirm the grant. Six months earlier, his wife had sent her junior chaplain, Brother Francis, to join them – ostensibly as a gesture of goodwill, though Prior Peter suspected that it was really to make sure that the proceeds of her gift were being spent wisely in the extension of the building.

‘We tell the count what we shall tell everyone else, including the king,’ growled the prior. ‘That they both ran away and now we know nothing of their whereabouts!’

‘That will satisfy no one, least of all King Henry,’ whimpered Osbert. ‘The girl was placed here in our safekeeping.’

This was a greater problem than even that of Count Eustace, as a month after the arrival of Brother Francis the king had sent them Lady Alice, his most recent ward. She was the orphaned daughter of Drogo de Peverel, dispatched to live at the priory until she could be found a suitable husband. Her father had been killed in a skirmish in Normandy and, with her mother already dead, his lands had escheated to the Crown and his daughter became the king’s responsibility. At eighteen, Alice had already shown herself to be a wilful girl of independent spirit, and Queen Maud, familiar with the task of dealing with her husband’s wards and cast-off mistresses, decided that the isolated location and stern discipline of Bermondsey would be a suitable place in which to keep the girl until she could be used for some political and financial advantage.

Unfortunately, the inevitable happened. Within a month of her arrival, Lady Alice’s seductive wiles easily overcame the vows of the immature young chaplain and soon she found herself with child. Even worse, the priest’s remorse at the discovery sent him out of his mind, into an explosion of violence.

When the awful results of this secret liaison burst on the small community a few days ago, Peter’s authoritarian character, nurtured in the rigid discipline of the Cluniacs’ strict interpretation of the Rule of Saint Benedict, overcame his common sense. Instead of admitting their failure to foresee such a catastrophe and delivering the problem to the king and Count Eustace, the prior decided to deal with the matter himself. Partly from a stubborn desire to regulate the affairs of his own priory, but even more from the fear of losing the lavish patronage of those who offered support to Bermondsey, Peter decided to act as he thought God and the Pope would require and wreaked terrible retribution on the errant chaplain.

Now they were burdened with the consequences of that decision and could do nothing but bow their heads and hope to weather the storm that soon would inevitably burst over them.

February 1196

‘We’ll get no further, Sir John,’ called the shipmaster from his place at the steering oar. ‘There’s not a breath of wind left and the fog’s thickening.’

Straining his eyes, John de Wolfe could just make out a low shore a few hundred yards away on the larboard side of the little cog Saint Radegund , but even that view came and went as greyish-yellow fog rolled in intermittent patches up the estuary of the Thames.

Читать дальше