WS turned to one side and picked up the sheaf of paper from the table. He crossed to the fireplace and deposited the sheets there. He struck a flint and set the flame to the paper.

‘There,’ he said as he watched the fire catch hold and the sheets curl and blacken. ‘Sometimes flame is the author’s best friend. No one will ever see or hear of my Domitian again. You have done me no small favour, Nick.’

‘In return, I shall ask for some information.’

‘If I can give it.’

‘You were once familiar with someone called Doll. Wapping Doll?’

WS had been crouching on his hams supervising the destruction of his script. Now he levered himself to his feet once more, groaning slightly and making some time-filling comment about old bones.

‘Wapping Doll? No, I don’t think so.’

‘Ulysses Hatch said differently.’

‘Did he now?’

‘Said that you and he had once had a falling-out over her.’

‘Never contradict a dead man,’ said WS.

‘Was he right?’

‘Why so insistent, Nick?’

Now it was my turn to feel uncomfortable.

‘Do you mean to ask,’ said WS, ‘whether I was once young and energetic and far from home in this great city, as you were yourself not so long ago? And glad of company?’

‘I suppose so,’ I said.

‘Young ravens must have food, you know. However, your question is a fair one, considering what you’ve done for me. I’ve never told you of my early years in London, have I?’

‘Not much,’ I said.

‘Then I shall tell you now.’

And he did.

Greenwich, London, 2005

The turbid waters of the Thames swirled around the bend in the river, like dirty cocoa in some gigantic drainpipe. Half a dozen workmen in their yellow hard hats fussed over the unloading of steel girders from a barge that was moored to a landing stage on the south shore. A telescopic crane mounted on the back of a huge truck was swinging the two-ton girders around in a wide arc to deposit them on the ground behind the wharf. The Millennium Dome was undergoing yet another facelift to try to establish some enterprise that might at last allow the place to start making a profit.

The foreman looked back at the unlovely hemisphere as he took out a narrow tin to roll himself a skinny cigarette. ‘Waste of time, this job. The bloody place is cursed!’ he muttered pessimistically.

Yelling ‘Take five!’ to the other men, he gestured to the crane driver. Stefan Kozlowski locked his controls and left a girder swaying gently twenty feet above the ground. Clambering down, he gratefully arched his aching back and, lighting a cigarette, ambled along the debris-strewn foreshore beyond the landing stage to stretch his legs. After he had walked a few yards, a glint of yellow caught his eye, and he bent to pick up what he hoped was a gold coin.

It was embedded in the old mud well above the high-tide mark, and when he pulled it, a small glass tube slid reluctantly from the filth with a sucking sound. When he wiped the top, it glistened, but when he scratched it with a fingernail, Stefan saw that what shone in the sunlight was just the peeling remains of gold leaf.

Idly, he pulled out the tight-fitting bung from the mud-smeared tube and shook out what was inside. To his disgust, it was just a piece of rotted wood, sodden and crumbling. He poked it around his palm with a finger, then shrugged and put it back in the vial. Just above him on the bank was one of the large rubbish skips that dotted the construction site around the Dome, and with an overarm toss that would have done credit to a Test cricketer, he sent the disappointing object sailing up into the skip.

Soon there was another yell from the foreman, ordering everyone back to work, and with a sigh Stefan trudged back towards his crane. He didn’t much like his job, but it was better than being unemployed in Cracow. As he passed under the load he had left suspended, disdaining all those stupid British Health and Safety Regulations, there was another frantic scream from his foreman.

Later, when the ambulances, the police cars and the duty undertaker’s van had left, a battered truck came to remove the skip, taking its load of hard core to add to the foundations of a new Church of the Holy Cross which was being built in Bromley.

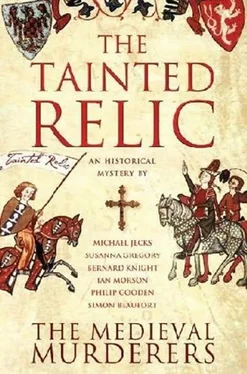

A small group of historical mystery writers, all members of the Crime Writers’ Association, who promote their work by giving informal talks and discussions at libraries, bookshops and literary festivals.

Simon Beaufortis the pseudonym under which Susanna Gregory writes her Sir Geoffrey Mappestone series of twelfth-century mysteries.

Bernard Knightis a former Home Office pathologist and professor of forensic medicine who has been publishing novels, non-fiction, radio and television drama and documentaries for more than forty years. He currently writes the highly-regarded Crowner John series of historical mysteries, based on the first coroner for Devon in the twelfth century; the tenth of which, The Elixir of Death , has recently been published by Simon & Schuster.

Michael Jecksis the author of the immensely popular Templar series, all set during the confusion and terror of the reign of Edward II. The most recent novels in the series are The Butcher of St Peter’s and A Friar’s Blood Feud . Michael was the Chairman of the Crime Writers’ Association in 2004-5.

Ian Morsonis the author of an acclaimed series of historical mysteries featuring the thirteenth-century Oxford-based detective, William Falconer.

Susanna Gregoryis the pseudonym under which she writes the Matthew Bartholomew series of mystery novels, set in fourteenth-century Cambridge, the most recent of which, The Tarnished Chalice , has just been published in hardback. She also writes historical mysteries under the name of ‘Simon Beaufort’.

Former schoolmaster Philip Goodenis the author of the Nick Revill series, a sequence of historical mysteries set in Elizabethan and Jacobean London, during the time of Shakespeare’s Globe theatre. The latest titles in the series are Mask of Night and An Honourable Murder .

***

[1]Often retired monks or members of the King’s or a wealthy magnate’s entourage, the corrodiary was the recipient of a ‘corrody’ or pension. The monastery would take a lump sum and then give food, lodging and sometimes spending money to the pensioner.

[2]A fair-sized horse of reasonable price, rounseys were used for almost any work apart from pulling carts. They were used as pack animals, but also as general riding horses by travellers or as warhorses by men-at-arms.