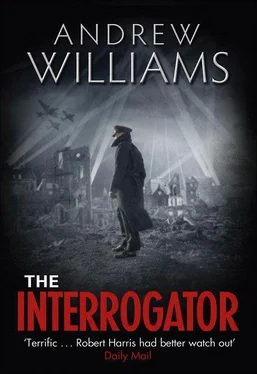

Andrew Williams

THE INTERROGATOR

Do not rescue people and take them along.

Do not worry about lifeboats… concern yourself only with your own boat and the effort to achieve the next success as quickly as possible. We must be hard in this war.

Standing Operational Order No. 154, Befehlshaber der Unterseeboote, Admiral Karl Dönitz

2210 GMT

HMS Culloden

16 September 1940

55°20N, 22°30W

At nightfall the rhythm of the storm quickened and by the middle of the first watch the sea was surging knee-high across the quarterdeck. Sharp plumes of spray swept along the ship’s sides into the darkness astern as she cut the top of one wave and raced to the bottom of the next. Douglas Lindsay — the Culloden ’s first lieutenant — stepped into the shelter of the gun platform and hoisted himself clear of the tide foaming white towards him. He had made his way through the ship from bridge to quarterdeck and everything was secure, the life-lines rigged and the watch as vigilant as it could be on such a night. It was North Atlantic foul, and yet he was glad of the excuse to be on the upper deck, salt spray stinging his face and hands. On the bridge, the atmosphere was thick with failure, the captain restless and ill tempered.

Bent almost double, he stepped out from beneath the canopy on the port side into the wind. Spray rattled against his oilskins and he reached for a lifeline to steady himself. It whipped from his grasp. At the same moment he heard a noise above the storm that was quite foreign. It was a deep hollow boom like the sound of a heavy door slamming in a cathedral cloister. The ship shuddered and heeled violently, pitching Lindsay forward on to his hands and knees. Thin blue smoke was rising from the starboard side below the funnel, ragged chunks of steel falling through it like a fountain. The wireless mast, the bridge and fo’c’sle were toppling to starboard and above the wail of the Atlantic Lindsay could hear the screech of grinding metal. Someone at his shoulder was moaning, ‘Please God no, please.’ Then it was over, over in a terrifying, bewildering instant. The entire forepart of the ship had gone and with it close to two hundred men.

Through the spray and smoke, Lindsay could see the for’ard section drifting away, the dark outline of stem and bow uppermost, the bridge and most of the mess deck beneath the waves. A torpedo had torn the ship in two and men he knew well were struggling below against a dark torrent. He could see them there, a savage kaleidoscope of images, but he could do nothing to help them.

A seaman pushed roughly past, forcing him to look away. The deck trembled beneath his feet as the wreck of the stern pitched awkwardly, tumbling from wave to wave. Then a torch light flashed across his face.

‘Thank God, sir…’ The junior engineer, Jones, sounded close to tears. ‘The captain’s…’ but his words were lost to the wind.

Lindsay ordered a headcount beneath the quarterdeck canopy. There were twenty-five seamen — the depth-charge party, the after-gun crew, engineer and stokers shivering in only their oily singlets and trousers.

‘They’ll miss us, sir,’ one of them chattered, ‘the other escorts, they’ll miss us soon, won’t they?.’

‘Yes,’ he said with as much conviction as he could manage. But their convoy and its escort ships were seven miles to the east and steaming away. The waves were twice the height of an ordinary house, rolling out of the darkness, their crests breaking into straggly white spindrift. The wreck was without power, the wireless and the lifeboats gone. Their best, their only hope was to cling to its heaving deck for as long as they were able. ‘My first command,’ and he almost laughed out loud.

Lindsay was twenty-four years old — tall, slim, with straw-blond hair, light-blue eyes, a soft voice and the faintest of Scottish accents. Before the war, he had considered a career in the quiet smoke-filled rooms of the Foreign Office. It might have suited him well — he was clever, articulate, close by disposition — but he had joined the volunteer reserve — the gentleman’s navy. Many times in the last two years he had reflected ruefully on this choice — diplomats never died in war.

Shoulders hunched, spray driving hard against his face, he staggered as far for’ard with the engineer, Jones, as he dared. A little more than a third of the ship had gone, ripped apart at the break of the fo’c’sle. The sea was pounding the flat steel bulkhead of Number Two boiler room.

‘It won’t hold for long,’ shouted Jones. As if to prove his point a huge wave thundered against it, forcing them to cower at the foot of the funnel, eyes stinging, salt spiking their throats.

Lindsay tugged at Jones’s arm and pointed back along the deck. There was a rumble and seconds later a crack as a star shell burst over the sea to starboard and began to fall slowly back. Half a dozen seamen were gathered about the anti-aircraft gun, their faces turned intently upwards like Baptists at a Sabbath prayer meeting.

Chief Petty Officer Hyde was in command: ‘No flares, sir, just twenty star shells.’

Lindsay glanced at his watch and was surprised to see that twenty minutes had passed since the explosion and it was almost half past ten. How long would the boiler room bulkhead hold? An hour, perhaps two, no more than two. ‘One shell every six minutes, Chief.’

Hyde’s face wrinkled in concentration as he counted: ‘Two hours. Yes, sir.’

They made their way down dark companionways and passages, unfamiliar in the torchlight, intensely close, shuddering and bucking. The wreck’s movement was sickening below and their mouths dry with fear that the bulkhead would collapse and catch them there.

‘There’s about three feet of water,’ said Jones, his torch flashing about the boiler room. ‘We’re too late here. We’ll have to shore up the engine room.’ The atmosphere was thick with hot choking fumes and the sea rang in the boiler room like a temple bell. They stepped back through the watertight door and Lindsay watched as Jones and the stokers struggled in anxious silence to position a timber brace against the bulkhead. Wide-eyed, white, they flickered in and out of the torchlight like figures in an old film.

‘It won’t last long when the boiler room floods,’ shouted Jones, the strain evident in his voice.

‘You’ve done well,’ said Lindsay with studied calm. They all needed some reassurance, some hope.

He left the engineer and returned to the quarterdeck where a second work party was trying to hoist depth charges over the side. They were stacked in racks at the stern, a score or more of them, enough high explosive to scatter the wreck across the Atlantic. Another star shell burst on the starboard side casting a restless splinter of light. Number nine — it was almost eleven o’clock. The stokers were back on the upper deck, shivering uncontrollably, singlets clinging wet beneath their life jackets. None of them would survive longer than half an hour in the water, not at this latitude, even in September. He was on the point of ordering them below to search for clothes when there was a muffled shout from the lookout on the gun platform above. Jones raced up the ladder and was back in an instant: ‘Flashing light to starboard, sir, perhaps two miles distance.’ He was breathless with hope.

‘Very good. Let’s fire another then and quick about it,’ said Lindsay as calmly as he could.

It was further twenty minutes before they could be sure, but as she pitched and rolled out of the darkness the seamen on the quarterdeck began to cheer. She was the dumpy little corvette HMS Rosemary from their escort group; there was no mistaking her open bridge and the sweep of her bow. Her Aldis lamp blinked madly at them.

Читать дальше